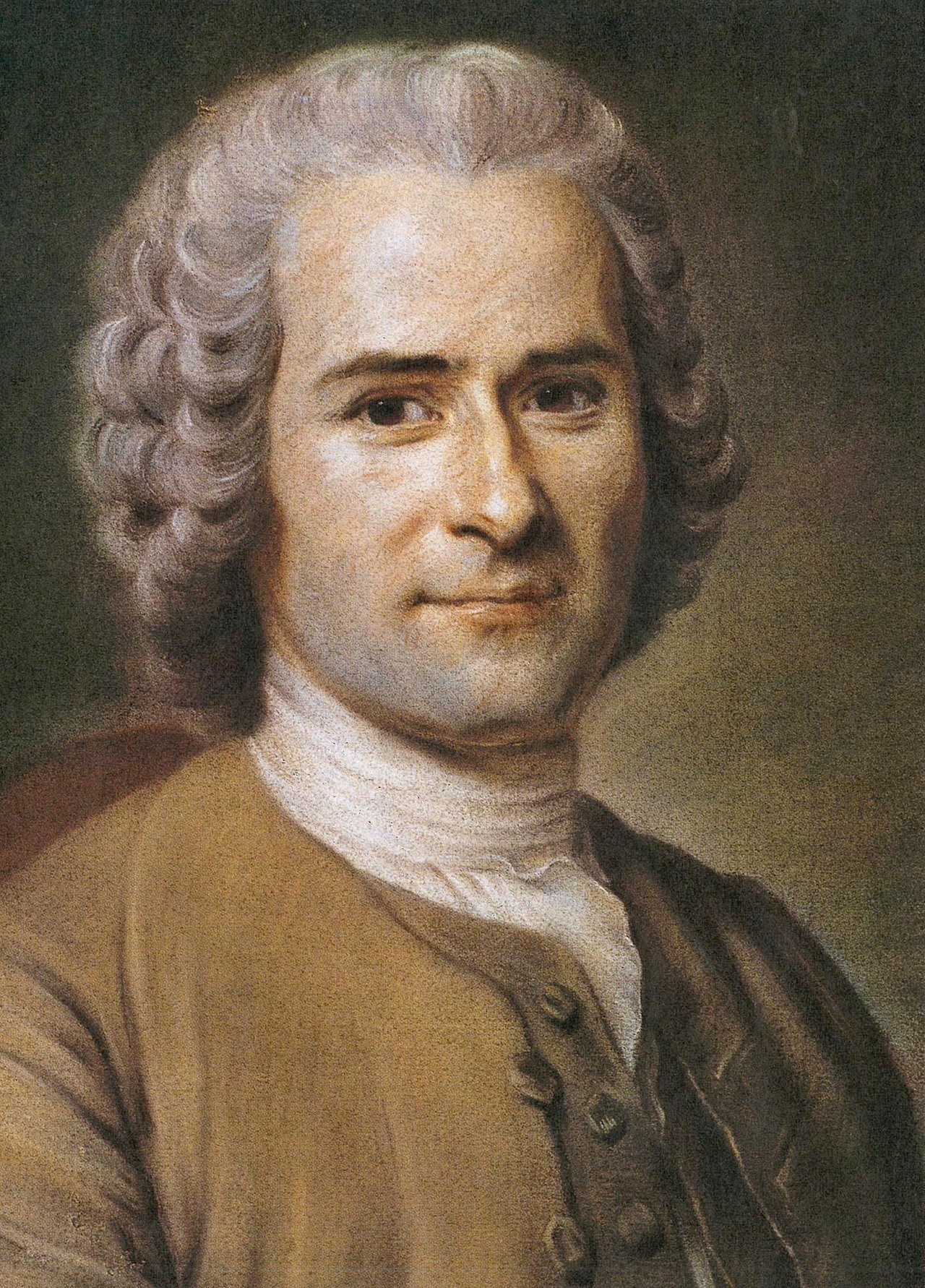

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778) was a French philosopher, writer, and composer whose ideas greatly influenced the Enlightenment, the French Revolution, and modern political and educational thought. Rousseau is best known for his works on political philosophy, including The Social Contract, where he argued that legitimate political authority lies with the collective will of the people, and Emile, which presented revolutionary ideas on education emphasizing natural development and individual freedom. His belief in the inherent goodness of humans and critique of society’s corrupting influence set him apart from contemporaries. Rousseau’s advocacy for democracy, equality, and personal liberty inspired later revolutionary movements, while his writings on nature and education influenced the Romantic movement. Though often controversial, his ideas on social and political reform continue to resonate, making him a central figure in the history of philosophy.

Early Life and Education (1712-1731)

Jean-Jacques Rousseau was born on June 28, 1712, in Geneva, Switzerland. Geneva, a city-state with a proud Calvinist tradition, influenced Rousseau’s thinking from an early age. He was the son of Isaac Rousseau, a watchmaker, and Suzanne Bernard, who tragically died shortly after giving birth to him. Rousseau’s upbringing was largely shaped by his father, who instilled in him a love for literature and a deep reverence for the works of classical authors. Rousseau’s childhood was marked by both intellectual stimulation and emotional upheaval.

After his mother’s death, young Rousseau was raised primarily by his father. Isaac was a man of culture and intellect, despite his modest profession, and he passed on these traits to Jean-Jacques. Isaac often read aloud to his son from works by authors such as Plutarch, Montaigne, and Cervantes. Rousseau later credited these early readings with awakening his love for storytelling and his interest in moral philosophy. Despite this intellectual foundation, Rousseau’s formal education was spotty at best.

When Rousseau was ten, his father fled Geneva to avoid imprisonment after a legal dispute. Rousseau was left in the care of his maternal uncle, who sent him and his cousin to board with a Calvinist pastor in the nearby village of Bossey. While there, Rousseau experienced a mixture of nurturing and abuse. Though he developed a strong sense of independence and a critical view of authority during this period, he also began to harbor a sense of insecurity and loneliness that would follow him throughout his life.

At the age of 12, Rousseau returned to Geneva and was apprenticed to an engraver. This apprenticeship proved to be an unhappy experience, as Rousseau found himself at odds with the mechanical and monotonous nature of the work. His master was harsh and abusive, which only intensified Rousseau’s growing disdain for the constraints of urban life and his yearning for freedom. At 16, in 1728, Rousseau ran away from Geneva, beginning the first of many journeys that would define his wandering, unsettled lifestyle.

Rousseau’s early experiences of displacement and his encounters with different forms of authority deeply influenced his later philosophical writings. His time spent with the pastor in Bossey, his difficult apprenticeship, and his subsequent flight from Geneva were all formative events that shaped his thinking about freedom, education, and society. These themes would come to dominate much of his later work, where he explored the tension between individual liberty and social constraints.

The Wanderer and Early Writings (1731-1749)

After fleeing Geneva in 1728, Rousseau wandered through various parts of Switzerland and France, living a vagabond life and taking on odd jobs. He eventually found refuge in Annecy, where he was taken in by Françoise-Louise de Warens, a Catholic noblewoman who had renounced her Protestant faith. Mme de Warens became a significant figure in Rousseau’s life, acting as both a maternal figure and later as a lover. She played a pivotal role in Rousseau’s conversion to Catholicism, a decision that caused him to lose his citizenship in Geneva.

For the next several years, Rousseau moved between different cities, living in Turin, Paris, and Lyon, among other places. During this period, he worked as a servant, a secretary, and a music teacher, while also continuing his self-education in various subjects, including philosophy, music, and mathematics. Despite his lack of formal schooling, Rousseau demonstrated a keen intellect and an insatiable curiosity.

In the 1740s, Rousseau began to make a name for himself in intellectual circles, particularly in Paris, where he formed friendships with prominent figures such as Denis Diderot, Jean d’Alembert, and other contributors to the Encyclopédie. Although Rousseau initially pursued a career in music, even writing an opera titled Les Muses galantes in 1745, it was his philosophical writings that eventually brought him to prominence.

Rousseau’s early works were deeply influenced by his personal experiences of poverty, marginalization, and his exposure to the contrasting worlds of the urban poor and the elite intellectual circles of Paris. These experiences sharpened his critical perspective on society and helped to shape his views on inequality, justice, and human nature. Although he initially supported many of the Enlightenment ideals of reason and progress, Rousseau would later come to challenge the dominant assumptions of his time, particularly those related to civilization and human development.

By the late 1740s, Rousseau had become an established figure within the Parisian intellectual community, though he remained an outsider in many respects. His early writings laid the groundwork for his later, more radical ideas about society and the state of nature, which would be fully articulated in his Discourse on the Sciences and Arts and Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men. These works would ultimately challenge the very foundations of Enlightenment thought and solidify Rousseau’s reputation as one of the most controversial and influential thinkers of his time.

Philosophical Foundations and the Discourse on Inequality (1750-1754)

Rousseau’s intellectual career took a dramatic turn in 1750 when he entered an essay competition sponsored by the Academy of Dijon. The topic of the contest was whether the progress of the sciences and arts had contributed to the purification of morals. Rousseau’s submission, titled Discourse on the Sciences and Arts, argued that the advancements in science and art had not led to moral improvement but rather to the corruption of humanity’s natural goodness. To the surprise of many, Rousseau won the competition, and his essay gained widespread attention.

The Discourse on the Sciences and Arts was Rousseau’s first major philosophical work, and it marked a sharp departure from the prevailing optimism of the Enlightenment. While many Enlightenment thinkers believed in the power of reason and progress to improve society, Rousseau argued that civilization had corrupted the fundamental nature of humanity. He posited that humans were naturally good but had been corrupted by the artificial structures and inequalities of society. This idea of the “noble savage,” living in a state of nature free from the vices of civilization, became one of Rousseau’s central philosophical concepts.

Rousseau’s critique of civilization and his romanticization of the natural state resonated with many, but it also provoked controversy. His ideas challenged the very foundations of Enlightenment thought and sparked debates among his contemporaries. The Discourse on the Sciences and Arts was followed by another significant work, the Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men, published in 1755. In this second discourse, Rousseau delved deeper into his critique of society, examining the roots of inequality and the consequences of private property.

The Discourse on Inequality is one of Rousseau’s most important and influential works. In it, he argues that inequality is not a natural condition but rather a product of social institutions. Rousseau traces the development of inequality to the establishment of private property, which he sees as the root of social divisions and human suffering. He contrasts the state of nature, in which humans were free, equal, and peaceful, with the corrupt and unequal conditions of civilized society.

Rousseau’s critique of inequality and his vision of a more egalitarian society were radical ideas for his time, and they would go on to influence later revolutionary movements, including the French Revolution. However, Rousseau’s ideas were not just a rejection of civilization; they were also a call to return to a more authentic and natural way of life. This tension between civilization and nature, and between individual freedom and social constraints, would continue to be a central theme in Rousseau’s later works, including his political treatise The Social Contract.

The Social Contract and Political Philosophy (1755-1762)

In 1762, Rousseau published The Social Contract, one of his most famous and enduring works. In this treatise, Rousseau laid out his vision of a just society based on the principles of equality, freedom, and popular sovereignty. The central idea of The Social Contract is that legitimate political authority is derived from the collective will of the people, rather than from divine right or the power of the ruling elite. Rousseau argues that individuals must come together to form a “social contract,” in which they agree to be governed by the general will, which represents the common good.

The Social Contract was a revolutionary work that challenged the traditional notions of monarchy and aristocracy that dominated European political thought at the time. Rousseau’s ideas about popular sovereignty and direct democracy influenced the political movements of the late 18th century, including the American Revolution and, more significantly, the French Revolution. His assertion that the general will—representing the collective interests of all citizens—should guide the laws of a society resonated deeply with revolutionaries who sought to challenge the established monarchies and aristocracies. Rousseau’s belief in the equality of all citizens and his critique of social inequalities made him a philosophical forefather to movements that demanded more just and egalitarian societies.

Rousseau’s ideas, however, were complex and open to different interpretations. In The Social Contract, he famously stated, “Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains,” highlighting the tension between individual freedom and the constraints imposed by society. Rousseau proposed that freedom could only be achieved when individuals collectively agreed to submit to the general will. However, this concept raised questions about how the general will could be determined and whether it could infringe on individual rights. Critics of Rousseau’s political philosophy argued that his ideas could justify authoritarian rule in the name of the general will, a critique that would later be echoed in discussions about the excesses of the French Revolution.

Rousseau’s work on political philosophy did not exist in a vacuum; it was deeply connected to his broader ideas about human nature, society, and morality. He believed that modern society, with its emphasis on private property, competition, and social distinctions, had corrupted the natural goodness of humanity. The Social Contract was an attempt to reconcile the need for social order with the preservation of human freedom and equality. Rousseau’s vision of a society governed by the general will was, in many ways, an idealistic response to the inequalities and injustices he observed in 18th-century Europe.

Despite its revolutionary ideas, The Social Contract was not immediately embraced by everyone. In fact, it was banned in France and Geneva, and Rousseau faced significant backlash from authorities and religious institutions. The book’s rejection of traditional power structures and its call for popular sovereignty were seen as threats to the established order. As a result, Rousseau’s life became increasingly difficult, and he was forced to flee from one place to another to avoid persecution.

Rousseau’s political philosophy also intersected with his views on religion. In The Social Contract, he discussed the role of religion in society and introduced the concept of civil religion, which he believed was necessary to promote social cohesion and moral unity. Rousseau argued that a civil religion should endorse values such as justice, duty, and patriotism, while avoiding the divisive dogmas of traditional religions. However, his ideas about religion were controversial, and they contributed to the condemnation of his works by religious authorities.

The publication of The Social Contract and Rousseau’s other major work of the same year, Emile, marked the height of his intellectual career, but they also ushered in a period of personal turmoil and exile. Rousseau’s radical ideas, particularly his critique of organized religion in Emile, drew the ire of both the Catholic Church and the Protestant authorities in Geneva. He was forced to flee France to avoid arrest, beginning a period of wandering that would characterize much of his later life.

Emile and Rousseau’s Educational Theories (1762-1765)

Alongside The Social Contract, Rousseau published another significant work in 1762, Emile, or On Education. This book, part philosophical treatise, part novel, explores Rousseau’s ideas on education and child development. Rousseau believed that education should be a process of natural development rather than formal instruction imposed by society. He argued that children should be allowed to develop according to their own interests and abilities, guided by their natural curiosity and instincts, rather than being molded to fit society’s expectations.

Emile is structured as a fictional account of the education of a boy named Emile, whom Rousseau raises according to his principles of natural education. The book is divided into five parts, corresponding to different stages of Emile’s development from infancy to adulthood. Rousseau’s educational philosophy in Emile is based on the idea that children are naturally good and that education should foster their innate qualities rather than suppress them.

One of the key themes in Emile is the importance of learning through experience. Rousseau believed that children should be encouraged to explore the world and learn from their interactions with it, rather than being confined to classrooms and forced to memorize facts. This emphasis on experiential learning was revolutionary at the time and has had a lasting impact on modern educational theory.

Rousseau’s ideas about education were deeply influenced by his broader philosophical beliefs about human nature and society. He argued that modern education, like modern society, had become corrupt and artificial, stifling the natural development of individuals. In Emile, he proposed an alternative vision of education that would allow individuals to develop freely and naturally, in harmony with their true selves.

However, Emile was not just a book about education; it also contained Rousseau’s views on religion, which proved to be highly controversial. In the section titled “Profession of Faith of the Savoyard Vicar,” Rousseau laid out his deistic beliefs, rejecting both organized religion and atheism in favor of a personal, intuitive faith in a benevolent creator. This section of the book was condemned by both Catholic and Protestant authorities, who saw it as a threat to established religious doctrines.

The backlash against Emile was swift and severe. The book was banned in Paris and Geneva, and Rousseau was accused of heresy. His works were publicly burned, and arrest warrants were issued for him. Faced with the threat of imprisonment, Rousseau fled France and sought refuge in Switzerland. However, his troubles were far from over, as he continued to face persecution and was forced to move frequently to avoid arrest.

Despite the controversy, Emile was widely read and had a profound influence on educational theory and practice. Rousseau’s ideas about natural education and the importance of respecting the individuality of children resonated with many educators and reformers. His emphasis on the emotional and moral development of children, rather than just their intellectual growth, was particularly influential in shaping modern approaches to education.

Rousseau’s educational theories also had a significant impact on the Romantic movement, which emphasized the importance of emotion, nature, and individualism. The Romantic poets and philosophers of the late 18th and early 19th centuries were deeply influenced by Rousseau’s ideas about the natural goodness of humanity and the corrupting influence of society. Rousseau’s vision of education as a process of self-discovery and personal growth resonated with the Romantic ideal of the individual as a unique and autonomous being.

Controversies and Exile (1765-1770)

The publication of The Social Contract and Emile brought Rousseau both fame and infamy. His ideas were celebrated by some as visionary and revolutionary, but they also attracted fierce opposition from religious and political authorities. As a result, Rousseau spent much of the 1760s on the run, moving from one place to another in search of safety and refuge.

After fleeing France in 1762, Rousseau initially sought refuge in Switzerland, hoping to return to his native Geneva. However, his reception in Geneva was far from welcoming. The authorities in Geneva, who had initially celebrated Rousseau as a native son, now viewed him as a dangerous radical. His works were banned, and he was condemned by both religious and political leaders. Feeling increasingly isolated and persecuted, Rousseau left Geneva and moved to the small town of Môtiers in the Swiss canton of Neuchâtel.

While in Môtiers, Rousseau found temporary peace and began to work on his autobiographical writings. However, his stay in Môtiers was cut short by rising tensions with the local authorities and the hostile actions of his neighbors. In 1765, after a mob attacked his house and pelted it with stones, Rousseau decided to leave Switzerland and seek refuge elsewhere.

Rousseau then accepted an invitation from David Hume, the Scottish philosopher, to come to England. Hume, who admired Rousseau’s work, offered him protection and a place to stay. Rousseau and Hume initially enjoyed a warm relationship, and Rousseau seemed to find some solace in the English countryside. However, their friendship quickly soured, and Rousseau became increasingly paranoid, suspecting Hume of conspiring against him.

Rousseau’s time in England marked a period of deep psychological distress. He became increasingly distrustful of those around him and began to believe that he was the victim of a vast conspiracy. His paranoia strained his relationships with friends and supporters, and he eventually broke with Hume in a bitter public dispute. Feeling betrayed and persecuted, Rousseau left England in 1767 and returned to France, despite the risks.

Upon his return to France, Rousseau continued to live a precarious and itinerant life. Although he was no longer actively pursued by the authorities, he remained an outsider in many respects, moving from place to place and relying on the generosity of friends and supporters. During this period, Rousseau worked on several of his later writings, including The Confessions, an autobiographical work in which he attempted to explain and justify his life and ideas.

The Confessions is one of Rousseau’s most personal and revealing works. Written in the form of an autobiography, it is a candid and often self-critical account of his life, his thoughts, and his struggles. Rousseau wrote The Confessions as a way of defending himself against his critics and explaining his actions. The work is notable for its introspective and confessional tone, as Rousseau delves into his inner thoughts and emotions, revealing both his strengths and weaknesses.

Despite his troubled life, Rousseau remained a prolific writer during this period. In addition to The Confessions, he worked on several other autobiographical and philosophical works, including Reveries of a Solitary Walker and Dialogues: Rousseau, Judge of Jean-Jacques, which offered deep reflections on his life, philosophy, and the trials he faced. These later works mark a period of intense introspection, as Rousseau sought to come to terms with the alienation and persecution he experienced. In these writings, Rousseau revisited many of the themes that had defined his earlier work, such as the tension between society and the individual, the pursuit of virtue, and the importance of remaining true to one’s nature.

Reveries of a Solitary Walker, written between 1776 and 1778, is particularly significant for its meditative style and its focus on personal reflection. The work consists of a series of ten “walks” or essays, in which Rousseau reflects on his life, his thoughts, and his relationship with nature. These walks are not just physical journeys but also intellectual and emotional explorations, where Rousseau grapples with his sense of isolation and his search for inner peace.

In Reveries, Rousseau expresses his profound love of nature and solitude, which had always been a refuge for him throughout his tumultuous life. He describes the restorative power of nature and the sense of freedom he feels when walking alone in the countryside. This connection to nature had been a central theme in Rousseau’s earlier works, particularly in Emile and The Social Contract, where he emphasized the importance of living in harmony with the natural world. In Reveries, this theme takes on a more personal and introspective dimension, as Rousseau uses his walks to escape from the troubles of society and reflect on his life.

Another important aspect of Reveries is Rousseau’s exploration of memory and self-identity. He often reflects on his past experiences, attempting to make sense of the events that led him to his current state of solitude and exile. Rousseau’s introspective writing style in Reveries reveals a man deeply concerned with his legacy and his place in the world. He struggles with feelings of betrayal, persecution, and misunderstanding, but he also finds solace in the idea that he has remained true to his principles, even if this has isolated him from others.

Dialogues: Rousseau, Judge of Jean-Jacques, written around the same time as Reveries, further illustrates Rousseau’s complex relationship with himself and his critics. The Dialogues are framed as a conversation between two characters: “Rousseau,” who defends the philosopher, and “Jean-Jacques,” who is a representation of Rousseau’s public persona. This dialogical structure allows Rousseau to explore his own self-perception and the way he has been perceived by others.

In the Dialogues, Rousseau expresses his frustrations with the way his ideas have been misunderstood and distorted by his contemporaries. He also reflects on the nature of truth and the difficulty of remaining virtuous in a corrupt society. The Dialogues are an attempt by Rousseau to reclaim his reputation and assert his true intentions in the face of widespread criticism. Like The Confessions, the Dialogues can be seen as a defense of Rousseau’s life and ideas, as well as a response to the personal attacks he endured.

Despite the bitterness and paranoia that permeate his later writings, Rousseau also expresses a sense of resignation and acceptance. By the time he wrote Reveries and Dialogues, Rousseau had come to terms with his position as an outsider and seemed more at peace with his solitude. His later works are less concerned with influencing society or reforming politics and more focused on personal reflection and the search for inner tranquility.

Rousseau’s health began to deteriorate in the late 1770s, and his final years were marked by physical and emotional decline. He continued to write, but his output slowed as his condition worsened. In 1778, at the age of 66, Rousseau accepted an invitation from the Marquis de Girardin to live at his estate in Ermenonville, a small village north of Paris. It was here that Rousseau spent his final days, surrounded by the natural beauty he cherished so deeply.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau died on July 2, 1778, under somewhat mysterious circumstances. Some reports suggest that he died of a stroke, while others hint at the possibility of suicide. Whatever the cause, Rousseau’s death marked the end of a remarkable and tumultuous life, one that had a profound and lasting impact on philosophy, politics, and education.

Rousseau was initially buried on the Île des Peupliers, a small island in the lake at Ermenonville, in a simple and peaceful setting that reflected his love of nature. In 1794, during the French Revolution, his remains were moved to the Panthéon in Paris, where they were placed alongside other great figures of the Enlightenment, including Voltaire. The decision to enshrine Rousseau in the Panthéon symbolized the enduring influence of his ideas, which had inspired the revolutionary movement and continued to shape the course of modern history.

Later Life and The Confessions (1770-1778)

As Jean-Jacques Rousseau entered the final decade of his life, he experienced a profound transformation from a political and philosophical provocateur to a more introspective and reflective figure. His later years, marked by exile, paranoia, and health issues, also saw the creation of some of his most personal and revealing works, particularly The Confessions. This autobiographical masterpiece, begun in 1765 and completed in 1770, provides an intimate look at Rousseau’s complex character and the tumultuous events that shaped his life.

Rousseau began writing The Confessions as a response to the intense scrutiny and criticism he faced throughout his life. By this point, his ideas had been both celebrated and condemned across Europe, and he felt a deep need to explain himself, to set the record straight. He famously declared that his autobiography would be an honest account of his life, “without disguise, without disguise, and without ornament.” Rousseau’s goal was to present himself to the world as he truly was, with all his flaws and virtues laid bare.

The Confessions is divided into twelve books, covering the entirety of Rousseau’s life, from his childhood in Geneva to his later years of exile and isolation. The work is notable for its candid and often self-critical tone. Rousseau does not shy away from revealing his mistakes, weaknesses, and insecurities, making The Confessions one of the earliest examples of modern autobiographical writing. The work is both a personal reflection and a defense of Rousseau’s ideas and actions, as he seeks to justify his choices and explain the motivations behind his often-controversial decisions.

Throughout The Confessions, Rousseau revisits many of the key themes that had defined his earlier works, such as the tension between nature and society, the corrupting influence of civilization, and the importance of individual freedom. However, in this autobiographical context, these themes take on a more personal dimension. Rousseau reflects on how his own experiences shaped his philosophy and how the events of his life informed his ideas about human nature, education, and politics.

One of the most striking aspects of The Confessions is Rousseau’s willingness to confront his own contradictions and shortcomings. He acknowledges his struggles with pride, vanity, and paranoia, and he reflects on the ways in which his relationships with others were often strained by his intense emotions and insecurities. Rousseau’s self-awareness and his willingness to confront his flaws make The Confessions a deeply human and relatable work, despite the often grandiose and idealistic nature of his philosophical writings.

The Confessions also provides valuable insights into Rousseau’s personal relationships, particularly his complex and often troubled connections with women. Rousseau’s relationships with women were a significant influence on his life and work, and he devotes considerable attention in The Confessions to discussing his experiences with figures like Mme de Warens and Thérèse Levasseur, his long-time partner. Rousseau’s reflections on love, desire, and companionship reveal a man who was deeply conflicted about his emotions and often struggled to reconcile his idealized views of love with the realities of his relationships.

Despite the personal nature of The Confessions, Rousseau also uses the work to defend his philosophical ideas. He attempts to explain the reasoning behind some of his most controversial positions, such as his critique of organized religion and his views on education. Rousseau’s tone in The Confessions is often defensive, as he seeks to clarify misunderstandings and refute the accusations that had been leveled against him by his critics.

After completing The Confessions in 1770, Rousseau continued to write, though his output slowed due to his declining health and increasing isolation. His later works, including Reveries of a Solitary Walker and Dialogues: Rousseau, Judge of Jean-Jacques, were more introspective and philosophical in nature, reflecting his growing detachment from the world around him. These writings reveal a man who was at once deeply reflective and increasingly resigned to his fate as an outsider and a misunderstood figure.

Despite the challenges he faced in his later years, Rousseau remained committed to his ideals and continued to influence the intellectual landscape of his time. His works, particularly The Confessions, would go on to inspire generations of writers and thinkers, shaping the development of modern autobiography and influencing the Romantic movement of the early 19th century. Rousseau’s willingness to confront his own imperfections and his unflinching honesty in The Confessions helped to establish the idea of the self as a subject worthy of serious philosophical inquiry.

Rousseau’s final years were spent in relative solitude, as he sought peace in nature and reflection. He had long believed that society had corrupted humanity’s natural goodness, and in his later works, Rousseau increasingly turned inward, seeking solace in nature and contemplation. His final writings reveal a man who, despite his personal turmoil and disillusionment with society, remained committed to the pursuit of truth and the exploration of the human condition. Rousseau’s belief in the fundamental goodness of humanity and his critique of the artificial constraints imposed by society continued to shape his thought, even as he withdrew from public life.

In works like Reveries of a Solitary Walker and Dialogues, Rousseau revisited many of the ideas that had defined his earlier writings, but now with a more introspective and personal focus. He reflected on his own experiences of persecution, isolation, and alienation, and how these had influenced his thinking about society, freedom, and individuality. These later works, though less overtly political than The Social Contract, still carried powerful messages about the importance of personal integrity and the dangers of conformity to social norms.

In Reveries of a Solitary Walker, Rousseau famously described his love for solitary walks in nature, which he saw as a way to reconnect with his inner self and escape the pressures and corruptions of society. The walks became a metaphor for Rousseau’s broader philosophical journey, as he sought to distance himself from the constraints of civilization and rediscover a more authentic, natural existence. Through these reflections, Rousseau expressed a sense of peace and acceptance that contrasted with the bitterness and paranoia of his earlier years. His connection to nature provided him with a refuge where he could find clarity and perspective, allowing him to come to terms with the hardships he had faced throughout his life.

At the same time, Rousseau’s Dialogues represented his continued efforts to defend his ideas and his reputation against those who had criticized and attacked him. The work is structured as a conversation between “Rousseau” and “Jean-Jacques,” with the former acting as a judge of the latter’s actions and character. This dialogical form allowed Rousseau to explore the tensions between his public persona and his private self, as well as the misunderstandings that had plagued his career. In the Dialogues, Rousseau wrestled with the challenges of being a public intellectual, reflecting on the difficulties of staying true to his principles in the face of constant opposition and misrepresentation.

Despite the introspective nature of his later works, Rousseau never fully abandoned his engagement with broader philosophical and political questions. His reflections on personal experience were always linked to his larger concerns about society and human nature. In Reveries and Dialogues, Rousseau continued to explore the idea that modern society had led to the degradation of human values and that true happiness could only be found by returning to a simpler, more natural way of life.

Rousseau’s final years were marked by a mixture of resignation and defiance. While he had largely retreated from the public sphere, he remained committed to the idea that his life and work had meaning and purpose. In The Confessions, Reveries, and Dialogues, he sought to assert control over his legacy, ensuring that his story would be told on his own terms. These writings reveal a man who, despite the many setbacks and challenges he had faced, refused to give up on his vision of a better world—a world in which individuals could live freely and authentically, in harmony with nature and their own true selves.

Rousseau’s death in 1778 brought an end to a life filled with both triumph and tragedy, but his influence only grew in the years that followed. The ideas he had developed throughout his life—about education, politics, religion, and human nature—would go on to shape the course of modern philosophy and political thought. His writings inspired revolutionaries, educators, and thinkers across Europe and beyond, and his legacy can be seen in the democratic movements, educational reforms, and Romantic ideals that emerged in the late 18th and 19th centuries.

In particular, Rousseau’s belief in the fundamental dignity and worth of the individual became a central tenet of modern democratic thought. His insistence that political authority should be based on the will of the people, rather than the arbitrary power of kings or elites, helped to lay the groundwork for the democratic revolutions that would reshape the world in the years following his death. Rousseau’s ideas about education, with their emphasis on natural development and the cultivation of individual potential, also had a profound impact on the way children were taught and raised, influencing educational theory and practice for generations to come.

Rousseau’s influence extended beyond philosophy and politics; he also had a lasting impact on literature, music, and the arts. His emphasis on emotion, nature, and individuality resonated with the Romantic movement, which sought to break away from the rationalism and formalism of the Enlightenment. Writers, poets, and artists of the Romantic era drew inspiration from Rousseau’s ideas, celebrating the power of imagination, the beauty of the natural world, and the importance of personal experience.

Ultimately, Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s legacy is a testament to the enduring power of ideas. Despite the many challenges he faced throughout his life, his work continues to inspire and provoke debate, reminding us of the importance of questioning the status quo and striving for a more just and humane society. Rousseau’s belief in the goodness of humanity, his critique of social inequality, and his vision of a world where individuals could live freely and authentically remain as relevant today as they were in his own time.

In the centuries since his death, Rousseau’s writings have been both celebrated and criticized, but they have never been ignored. His bold ideas, his passionate defense of freedom and equality, and his willingness to challenge the norms of his society have secured his place as one of the most important and influential thinkers in history. Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s life and work continue to inspire those who seek to understand the complexities of human nature and the possibilities for a better world.

Legacy and Impact

Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s legacy is one of the most far-reaching in the history of Western thought. His ideas on politics, education, philosophy, and society influenced not only his contemporaries but also future generations of thinkers, revolutionaries, and educators. Rousseau’s vision of human nature, individual freedom, and social equality helped to shape the development of modern political ideologies, particularly in the areas of democracy and social justice. His impact extends across various fields, including philosophy, political theory, education, literature, and the arts, making him a central figure in the intellectual history of the modern world.

One of Rousseau’s most significant contributions was his theory of popular sovereignty, which became a cornerstone of modern democratic thought. In The Social Contract (1762), Rousseau argued that legitimate political authority arises only from the consent of the governed. This radical idea challenged the prevailing notion of divine-right monarchy and aristocratic rule, suggesting instead that political power should be based on the will of the people. Rousseau’s concept of the “general will,” or the collective will of the citizenry, became a foundational principle for democratic governance. His insistence that the people should have a direct say in the laws and policies that govern them had a profound influence on the democratic revolutions of the late 18th century, particularly the American and French Revolutions.

The influence of Rousseau’s political ideas can be seen in the rhetoric and principles of the French Revolution, where his writings were widely read and quoted by revolutionary leaders. Rousseau’s vision of a republic based on equality, freedom, and popular sovereignty resonated deeply with the revolutionary movement in France, and his works were often invoked as justifications for radical political change. The Jacobins, who led the most radical phase of the Revolution, embraced Rousseau’s ideas about direct democracy and the moral superiority of the common people over corrupt elites. Even after the Revolution, Rousseau’s ideas continued to shape the development of republican thought in France and beyond.

Rousseau’s impact on education was equally transformative. His book Emile, or On Education (1762) revolutionized the way people thought about childhood and education. Rousseau’s emphasis on the natural development of the child and the importance of education that nurtures rather than represses innate human goodness was a radical departure from the strict, authoritarian methods of traditional education. Rousseau believed that education should be centered on the needs and interests of the child, rather than on rigid curricula and rote learning. This child-centered approach laid the groundwork for modern educational theories, including those of Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi, Friedrich Froebel, and later, John Dewey. Rousseau’s ideas about education also influenced the development of progressive education movements in the 19th and 20th centuries, which emphasized experiential learning, creativity, and the development of critical thinking skills.

Rousseau’s philosophy also had a profound impact on the Romantic movement, which emerged in the late 18th and early 19th centuries as a reaction against the rationalism and formalism of the Enlightenment. Rousseau’s emphasis on emotion, nature, and individuality resonated with Romantic writers, poets, and artists, who sought to express the deep emotional and spiritual dimensions of human experience. Rousseau’s celebration of nature as a source of purity and inspiration became a central theme in Romantic literature, as did his belief in the importance of personal authenticity and the rejection of societal conventions. Writers like William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe were deeply influenced by Rousseau’s ideas, as were painters and composers of the Romantic era.

Rousseau’s influence extended beyond politics, education, and the arts; his philosophical ideas about human nature and society also had a lasting impact on the development of modern psychology and anthropology. His belief in the fundamental goodness of humanity and his critique of the corrupting effects of civilization challenged the dominant Hobbesian view that human beings are naturally selfish and brutish. Rousseau’s idea that society imposes artificial constraints on human freedom and happiness paved the way for later critiques of modernity and industrialization, including those of Karl Marx and Sigmund Freud. Rousseau’s exploration of the tension between the individual and society also influenced existentialist thinkers like Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus, who grappled with the question of how to live authentically in a world filled with social pressures and moral ambiguities.

Rousseau’s work continues to be relevant in contemporary discussions about politics, education, and social justice. His critique of social inequality and his advocacy for a more just and egalitarian society resonate with modern movements for human rights, environmental sustainability, and democratic reform. Rousseau’s ideas about the importance of individual freedom, the dangers of unchecked authority, and the need for a social contract based on mutual respect and cooperation remain central to debates about the nature of democracy and the role of government in protecting the rights and freedoms of its citizens.

In addition to his political and philosophical influence, Rousseau’s personal writings, particularly The Confessions and Reveries of a Solitary Walker, have had a lasting impact on the development of modern autobiographical literature. Rousseau’s candid exploration of his own thoughts, emotions, and experiences set a new standard for self-reflective writing, influencing later autobiographers and memoirists. His willingness to confront his own flaws and contradictions made The Confessions a pioneering work in the genre of autobiography, and his focus on the inner life of the individual foreshadowed the introspective tendencies of modern literature.

Ultimately, Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s legacy is one of bold ideas and enduring influence. His belief in the inherent goodness of humanity, his critique of societal corruption, and his vision of a more just and free world continue to inspire thinkers, activists, and educators. Rousseau’s work challenges us to question the assumptions of our own society and to imagine new possibilities for human flourishing. His ideas remind us that the pursuit of truth, freedom, and equality is an ongoing journey, one that requires constant reflection and a commitment to the betterment of humanity.