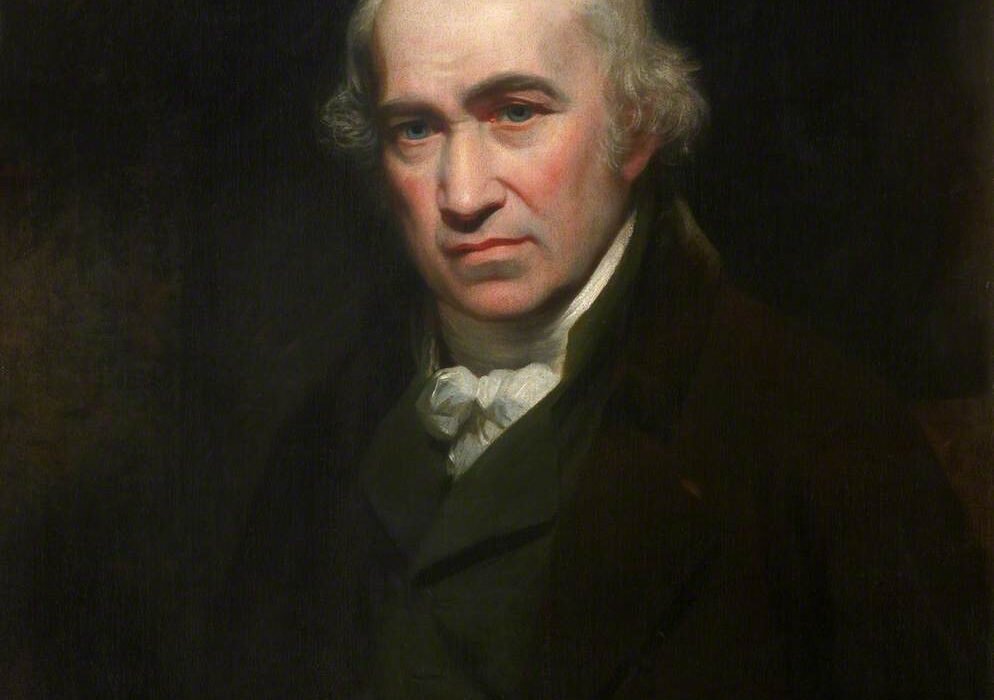

John Adams (1735–1826) was a key Founding Father and the second President of the United States, serving from 1797 to 1801. A lawyer by profession, Adams played a crucial role in the American Revolution, advocating for independence and drafting the Declaration of Independence alongside Thomas Jefferson. As a staunch supporter of American sovereignty, he was instrumental in negotiating the Treaty of Paris, which ended the Revolutionary War. Adams also served as the first Vice President under George Washington. His presidency was marked by challenges, including the Quasi-War with France and internal political divisions. Despite these, Adams is remembered for his commitment to republican principles and his advocacy for a strong central government. His political legacy is complemented by his extensive correspondence with his wife, Abigail Adams, and his role in shaping the early republic. Adams’ contributions to the foundation of the United States are celebrated for their enduring impact on American democracy.

Early Life and Education (1735-1755)

John Adams was born on October 30, 1735, in the small town of Braintree, Massachusetts, now part of Quincy. The first of three sons born to John Adams Sr. and Susanna Boylston Adams, John grew up in a modest, yet influential Puritan family. His father, a deacon in the Congregational Church, was a respected farmer and a community leader who held various public offices, including that of a selectman and tax collector. The Adams family, known for their piety and dedication to hard work, instilled in John the values of duty, discipline, and education.

From an early age, Adams showed a keen intellect and a curiosity about the world. His father, recognizing his son’s potential, placed great emphasis on his education, which was not a given for many in colonial New England. Adams initially attended a local school in Braintree, where he learned the basics of reading, writing, and arithmetic. However, he was not particularly fond of school at first and often found the repetitive lessons dull. It wasn’t until he came under the tutelage of Joseph Marsh, a more inspiring teacher, that Adams began to develop a love for learning.

In 1749, at the age of 14, Adams was sent to Harvard College, which was primarily a seminary at the time. Harvard exposed him to a broader array of subjects and ideas, including philosophy, mathematics, science, and rhetoric. While there, Adams began to question his initial desire to become a clergyman, a profession that his father had envisioned for him. He found himself more drawn to the law and the study of government, particularly influenced by the works of classical philosophers and Enlightenment thinkers such as John Locke. These ideas about individual rights and the role of government would later become central to his political beliefs.

Adams graduated from Harvard in 1755, placing in the middle of his class, which was typical for the time. Despite his unremarkable academic standing, Adams left Harvard with a deep intellectual curiosity and a strong foundation in the classics and modern thought. His years at Harvard also marked the beginning of a lifelong habit of keeping a diary, where he recorded his thoughts on education, morality, and politics.

After graduating, Adams returned to Braintree, where he faced the challenge of choosing a career path. His father encouraged him to pursue the ministry, but Adams was not enthusiastic about this prospect. Instead, he decided to become a schoolteacher in Worcester, Massachusetts, to support himself while he considered his future. Teaching gave Adams time to reflect on his ambitions and future goals. He found the work fulfilling but not his true calling.

During his time in Worcester, Adams began to study law under the mentorship of James Putnam, one of the most prominent lawyers in the colony. The study of law captivated Adams, who saw it as a means to not only earn a living but also to engage with the important political and social issues of the day. By 1758, after years of study and apprenticeship, Adams was admitted to the bar and began practicing law in Braintree.

John Adams’ early years were marked by a blend of rigorous education, intellectual curiosity, and a deep sense of duty instilled by his Puritan upbringing. These formative experiences laid the groundwork for his later career as a lawyer, revolutionary, and statesman, as he developed a keen understanding of the law and a growing interest in the political theories that would one day influence the founding of a new nation.

Legal Career and Entry into Politics (1755-1770)

After completing his education and apprenticeship, John Adams embarked on a legal career that would soon become a stepping stone to his involvement in the burgeoning American independence movement. His legal practice began in his hometown of Braintree, where he handled a variety of cases, ranging from property disputes to criminal defense. Adams’ reputation as a competent and principled lawyer quickly grew, and he soon found himself involved in more significant and complex cases.

Adams’ commitment to the rule of law and justice was evident early in his career. He firmly believed in the importance of an impartial legal system and the protection of individual rights, principles that would later inform his political philosophy. One of the most famous examples of his legal integrity came in 1761 when he observed the arguments in the case of Paxton’s Case of Writs of Assistance. James Otis, a Boston lawyer, argued against the British Crown’s issuance of writs of assistance, which allowed customs officers to search any property for smuggled goods without specific warrants. Otis’ passionate defense of the colonists’ rights deeply influenced Adams, solidifying his belief in the need for a government that was bound by laws and accountable to the people.

The next pivotal moment in Adams’ legal career came in 1765 with the Stamp Act, a British law that imposed a direct tax on the colonies, requiring that many printed materials in the colonies be produced on stamped paper produced in London, carrying an embossed revenue stamp. The Act was met with widespread outrage in the colonies, and Adams became one of its most vocal critics. He wrote a series of essays under the pseudonym “Humphrey Ploughjogger” in which he articulated the colonists’ objections to the Stamp Act, arguing that it violated their rights as Englishmen to be taxed only by their own representatives. These essays helped to galvanize colonial opposition to the Act and propelled Adams into the political spotlight.

Adams’ growing reputation as a defender of colonial rights led to his involvement in one of the most controversial cases of his career: the defense of the British soldiers involved in the Boston Massacre of 1770. On March 5, 1770, a confrontation between British soldiers and a crowd of colonists in Boston escalated into violence, resulting in the deaths of five colonists. The incident inflamed anti-British sentiments, and the soldiers were charged with murder. Despite the intense public outcry, Adams agreed to defend the soldiers, believing that everyone was entitled to a fair trial and that justice should be served impartially.

Adams’ defense was masterful. He argued that the soldiers had acted in self-defense and that the violence was a result of the chaotic situation rather than a deliberate attack. His eloquent and reasoned defense led to the acquittal of six of the eight soldiers, with two found guilty of manslaughter rather than murder. Adams’ willingness to take on such an unpopular case demonstrated his deep commitment to the rule of law and earned him both respect and criticism.

While the Boston Massacre case was a turning point in Adams’ legal career, it also marked his full entry into the political arena. The case, along with his writings and public speeches, positioned him as a leading figure in the growing movement against British rule. In 1770, Adams was elected to the Massachusetts House of Representatives, where he joined other prominent leaders in opposing British policies and advocating for the rights of the colonies.

Adams’ legal career was characterized by a steadfast dedication to justice and the principles of liberty. His experiences as a lawyer, particularly his involvement in high-profile cases like the Boston Massacre, helped to shape his political philosophy and prepared him for the critical role he would soon play in the fight for American independence.

Role in the American Revolution (1770-1776)

John Adams’ role in the American Revolution was pivotal, as he transitioned from a respected lawyer and local politician to a national leader advocating for independence from British rule. The period from 1770 to 1776 saw Adams at the forefront of the revolutionary movement, where his intellectual rigor, eloquence, and unwavering commitment to the cause of liberty made him one of the most influential figures of the era.

The years following the Boston Massacre were marked by increasing tensions between the American colonies and the British government. Adams was deeply involved in the resistance to British policies, working alongside other prominent leaders such as Samuel Adams, his cousin, and John Hancock. As a member of the Massachusetts legislature, Adams played a key role in organizing opposition to the various acts imposed by the British Parliament, including the Townshend Acts, which levied taxes on essential goods, and the Tea Act, which led to the Boston Tea Party in 1773.

Adams’ political philosophy was heavily influenced by his legal background and his study of Enlightenment thinkers. He believed that the colonies had the natural right to govern themselves and that the British government’s actions were not only unjust but also a violation of the colonists’ rights as Englishmen. This belief was articulated in a series of essays he wrote, which were widely circulated and helped to shape public opinion in favor of independence.

In 1774, Adams was elected as a delegate to the First Continental Congress, a gathering of representatives from the thirteen colonies in response to the Coercive Acts, which were enacted by the British in retaliation for the Boston Tea Party. At the Congress, Adams quickly emerged as a leading voice for the rights of the colonies. He was a member of the committee that drafted the Declaration of Rights and Grievances, which outlined the colonies’ objections to British policies and called for the restoration of their rights.

Adams’ contributions to the Continental Congress continued in 1775 when he was appointed as a delegate to the Second Continental Congress. This Congress convened shortly after the battles of Lexington and Concord, which marked the beginning of armed conflict between colonial militias and British troops. Adams recognized that the time for reconciliation with Britain had passed and began to advocate for full independence. He played a crucial role in persuading other delegates to support the creation of a Continental Army, with George Washington appointed as its commander-in-chief.

As the revolutionary fervor grew, Adams became increasingly vocal in his support for independence. He was a key member of the committee tasked with drafting the Declaration of Independence, alongside Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert R. Livingston. Although Adams was originally expected to draft the document due to his strong advocacy for independence, he recognized Jefferson’s superior writing skills and persuaded him to take the lead. Adams’ role in the drafting process was critical; he provided substantial input and was instrumental in convincing the Continental Congress to adopt the Declaration.

Adams’ leadership was not limited to the drafting of the Declaration. Throughout the sessions of the Continental Congress, he worked tirelessly behind the scenes to build consensus among the delegates. He understood the importance of uniting the colonies in the face of British oppression, and he used his considerable diplomatic skills to achieve this goal. Adams’ persuasive arguments and unyielding dedication to the cause helped to sway undecided delegates, ultimately leading to the unanimous adoption of the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776.

During this period, Adams also served on numerous committees, contributing to the development of the nascent nation’s governance and military strategy. One of his most significant contributions was his work on the Board of War and Ordnance, where he helped to oversee the organization of the Continental Army and the procurement of supplies. Adams was deeply involved in the logistical and strategic challenges of the war effort, working closely with military leaders and fellow delegates to ensure the colonies were prepared to sustain a protracted conflict with Britain.

Adams’ contributions to the revolution extended beyond the political and military spheres. He was also deeply concerned with the future governance of the independent states. In 1776, he wrote the Thoughts on Government, a pamphlet that laid out his vision for republican government. In this influential work, Adams argued for the separation of powers within government, advocating for a balanced system with a strong executive, an independent judiciary, and a bicameral legislature. His ideas significantly influenced the development of state constitutions and later the United States Constitution.

Despite his numerous contributions, Adams often found himself at odds with other leaders of the revolution, including his cousin Samuel Adams and fellow delegates such as Thomas Paine and Thomas Jefferson. His sometimes abrasive personality and strong opinions occasionally led to conflicts, but his commitment to the cause of independence remained unwavering. Adams was not one to shy away from difficult decisions or unpopular positions if he believed they were in the best interest of the colonies.

As the revolution progressed, Adams’ role as a statesman continued to evolve. By the time the Declaration of Independence was signed, Adams had firmly established himself as one of the most important figures in the American struggle for independence. His relentless advocacy for the rights of the colonies, his strategic thinking, and his deep understanding of the principles of government made him indispensable to the revolutionary cause.

The period from 1770 to 1776 was a time of immense change and challenge for John Adams. From his early involvement in the resistance to British policies to his central role in the Continental Congress and the drafting of the Declaration of Independence, Adams emerged as a key architect of American independence. His contributions during these critical years laid the foundation for the creation of the United States and set the stage for his later roles as a diplomat, vice president, and president.

Diplomatic Efforts and the Treaty of Paris (1776-1783)

Following the Declaration of Independence, John Adams took on an even more challenging and vital role: securing international support and recognition for the fledgling United States. His diplomatic efforts during the Revolutionary War were crucial in securing the resources and alliances necessary for the colonies to succeed against the might of the British Empire.

In 1777, Adams was appointed by the Continental Congress as a commissioner to France, joining Benjamin Franklin and Arthur Lee in Paris. The primary goal of this mission was to secure French support for the American cause, both in terms of military aid and financial assistance. France, eager to weaken its long-time rival Britain, was receptive to the idea of supporting the American colonies, but the task of formalizing this support was fraught with challenges.

Adams arrived in France in 1778 and quickly realized that the diplomatic landscape was more complex than he had anticipated. Benjamin Franklin, who was already well-established in Paris and widely admired by the French, took a more relaxed and social approach to diplomacy, relying on his charm and wit to win over the French court. Adams, by contrast, was more straightforward and businesslike, focusing on the practicalities of the alliance. This difference in style led to some friction between the two men, though they maintained a working relationship for the sake of the mission.

Despite the difficulties, the efforts of the American delegation bore fruit. In 1778, France formally recognized the United States and entered into a military alliance with the new nation. This alliance was a turning point in the Revolutionary War, as French military and naval support played a critical role in several key battles, including the decisive Siege of Yorktown in 1781.

Adams’ time in Europe was not limited to France. In 1779, he returned to Massachusetts briefly before being sent back to Europe in 1780, this time with the added responsibility of securing loans and negotiating treaties with other European powers. He traveled to the Dutch Republic, where he faced the daunting task of persuading the Dutch government and financial institutions to support the American cause. The Dutch were initially hesitant, but Adams’ persistence paid off. In 1782, the Dutch Republic became the second nation, after France, to formally recognize the United States, and Adams secured a critical loan that helped to sustain the American war effort.

Adams’ most significant diplomatic achievement came in 1783, when he was appointed as one of the American commissioners, along with Benjamin Franklin and John Jay, to negotiate the Treaty of Paris, which would formally end the Revolutionary War. The negotiations were complex and contentious, involving not only the United States and Britain but also France and Spain, each with its own interests and agendas.

Adams, known for his tenacity and keen legal mind, played a crucial role in these negotiations. He was particularly focused on securing favorable terms for the United States, including recognition of American independence, the establishment of borders, and access to fishing rights in the North Atlantic. Despite the challenges posed by competing interests, the American delegation succeeded in securing a treaty that met most of their objectives. The Treaty of Paris, signed on September 3, 1783, officially ended the war and recognized the United States as an independent nation.

Adams’ success in these diplomatic missions was a testament to his skills as a negotiator and his deep commitment to the American cause. His work in Europe not only helped to secure the independence of the United States but also laid the groundwork for its future relationships with European powers.

After the signing of the Treaty of Paris, Adams remained in Europe for several more years, serving as the first American minister to Britain from 1785 to 1788. This was a challenging post, as relations between the two nations were still strained in the aftermath of the war. Adams’ tenure in London was marked by frustration and limited success, but it provided him with valuable experience and a deep understanding of international relations.

By the time Adams returned to the United States in 1788, he had spent nearly a decade abroad, away from his family and the political developments in America. His diplomatic service had been demanding and often thankless, but it was essential in securing the nation’s independence and establishing its place on the world stage.

Vice Presidency under George Washington (1789-1797)

After returning to the United States in 1788, John Adams found a nation in transition. The Articles of Confederation had proven inadequate for governing the new country, leading to the Constitutional Convention of 1787, where a new framework of government was devised. Adams, having been in Europe at the time, did not participate in the drafting of the Constitution, but his ideas about government, particularly those articulated in his Thoughts on Government, had influenced the delegates.

With the ratification of the Constitution in 1788, the United States prepared to elect its first president. George Washington was the obvious choice, revered across the nation for his leadership during the Revolutionary War. Adams, whose reputation as a statesman and diplomat was also highly respected, was chosen as the first vice president. The selection process for vice president was indirect; Adams, receiving the second-highest number of electoral votes after Washington, was thus elected to the office.

Adams assumed the vice presidency in 1789, a role that was not well-defined in the Constitution and was often considered secondary and largely ceremonial. The vice president’s primary duty was to preside over the Senate, casting a tie-breaking vote when necessary. Adams took this responsibility seriously, attending Senate sessions regularly and actively participating in debates. However, he found the position frustratingly limited, referring to it as “the most insignificant office that ever the invention of man contrived or his imagination conceived.”

Despite the frustrations of the office, Adams made significant contributions during his tenure as vice president. He played a key role in establishing the protocols and precedents of the new government, often mediating between competing factions in the Senate. His deep understanding of law and governance was invaluable in shaping the legislative process during these formative years.

One of Adams’ notable actions as vice president was his support for a strong executive branch. He believed that the president needed sufficient authority to govern effectively, and he opposed efforts by some in the Senate to curtail executive power. This stance sometimes put him at odds with other members of the emerging Federalist Party, including Alexander Hamilton, who had a different vision for the balance of power within the government.

Adams’ relationship with George Washington was complex. While they shared a commitment to the success of the new nation, they differed in their political philosophies. Washington, though generally supportive of Adams, was more aligned with Alexander Hamilton’s Federalist vision, which emphasized a strong central government and a loose interpretation of the Constitution. Adams, while also a Federalist, was wary of Hamilton’s aggressive approach and his centralizing tendencies. This sometimes led to tensions between the two men, though they managed to maintain a professional relationship throughout Adams’ vice presidency.

One of the most significant challenges during Adams’ vice presidency was navigating the growing political divide between the Federalists, led by Hamilton, and the Democratic-Republicans, led by Thomas Jefferson. The emergence of political parties began to shape the new American political landscape, with Jefferson and his allies advocating for states’ rights and a more limited federal government, while Hamilton and his supporters pushed for a strong central authority and an expansive federal role.

Adams’ own political views were somewhat aligned with the Federalists but reflected a concern for balancing power and preventing any one branch of government from becoming too dominant. This nuanced position often placed him in the middle of political debates, trying to mediate between competing factions. His efforts to maintain harmony and support Washington’s administration were crucial during these early years of the republic, even as he struggled with the limitations of his role and the partisan conflicts that arose.

Despite these challenges, Adams was an important figure in Washington’s administration. He helped to establish the procedures and practices of the executive branch and supported key initiatives, including the creation of the first executive departments and the establishment of the federal judiciary. His experience and knowledge were invaluable in these formative years, helping to shape the structure and function of the new government.

In 1796, Adams was elected as the second President of the United States, succeeding George Washington. His election marked a significant transition for the nation, as it was the first time in American history that power was transferred from one political leader to another through a democratic process. Adams’ presidency would present its own set of challenges and opportunities, setting the stage for the next phase of his political career.

Presidency (1797-1801)

John Adams assumed the presidency on March 4, 1797, following George Washington, whose two terms had set numerous precedents for the newly established American government. Adams, a prominent Federalist and one of the key figures in the American Revolution, faced a complex array of challenges as he embarked on his term as the second President of the United States. His presidency was marked by significant political, diplomatic, and domestic issues that would leave a lasting impact on the nation.

The primary challenge Adams confronted upon taking office was the deteriorating relationship with France. The United States was embroiled in a quasi-war with France, an undeclared naval conflict that arose from disputes over maritime rights and the French interference with American shipping. The immediate cause of this conflict was the XYZ Affair, a diplomatic incident that dramatically heightened tensions between the two nations.

In 1797, French officials, later identified as X, Y, and Z, had demanded bribes and loans from American envoys as a precondition for negotiations to address the disputes between the countries. This demand, which was revealed to the American public through the reports of the envoys, incited widespread outrage and led to a surge in anti-French sentiment. Federalists, led by influential figures like Alexander Hamilton, saw the incident as an opportunity to galvanize public support for a more aggressive stance against France.

Despite mounting pressure from his party and the American public, Adams remained committed to avoiding a full-scale war. His decision was driven by a belief that engaging in war with France would be detrimental to the United States’ interests and could jeopardize the fragile unity of the young nation. Adams’ approach to the crisis was characterized by his dedication to diplomacy and his cautious assessment of the potential consequences of military conflict.

In pursuit of peace, Adams took several critical steps to de-escalate the situation. He dispatched a peace mission to France, appointing former President John Jay and other diplomats to negotiate a resolution. This decision was controversial, particularly among Federalists who favored a more confrontational approach. Adams’ commitment to diplomacy ultimately paid off when the Treaty of Mortefontaine was signed in 1800. This treaty ended the hostilities between the United States and France, restoring peaceful relations and averting a potentially devastating war. Although this achievement was significant, it came at a political cost for Adams. His decision to pursue diplomacy over war was met with criticism from Federalist leaders who felt he had compromised American interests.

Domestically, Adams’ presidency was marked by a growing political divide. The Federalist Party, which Adams represented, was increasingly fractured. Internal disagreements within the party and the rise of political opposition from the Democratic-Republicans, led by Thomas Jefferson, created a contentious environment. The Federalist Party was split between more moderate elements and those, like Alexander Hamilton, who advocated for a strong central government and an expansive federal role.

One of the most contentious domestic issues during Adams’ presidency was the passage of the Alien and Sedition Acts in 1798. These laws were introduced by the Federalist-controlled Congress and signed into law by Adams amidst fears of internal subversion and foreign influence. The Alien Act gave the president the authority to deport foreigners deemed dangerous, while the Sedition Act criminalized the publication of false or malicious statements against the government.

The Alien and Sedition Acts were deeply controversial and sparked significant opposition. Critics, particularly from the Democratic-Republican Party, argued that the laws were a violation of constitutional rights and an attempt to suppress political dissent. Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, in particular, condemned the acts as an infringement on civil liberties. The controversy surrounding the acts fueled the growing partisan divide and contributed to Adams’ declining popularity.

The political climate of the time was increasingly polarized, with the Federalists and Democratic-Republicans engaging in intense and often personal attacks. The election of 1800, in which Adams sought re-election, was marked by particularly harsh campaigning. Jefferson, running as the Democratic-Republican candidate, was a formidable opponent who challenged Adams on numerous fronts. The campaign was characterized by accusations and criticisms, reflecting the deep divisions within the American political landscape.

Jefferson ultimately won the presidency in the election of 1800, marking the first peaceful transfer of power between opposing political parties in American history. The result was a significant moment in the evolution of American democracy, demonstrating the stability and resilience of the nation’s political system. Adams’ acceptance of the election outcome and his decision to relinquish power without dispute were pivotal in reinforcing the principles of democratic governance.

During the final months of his presidency, Adams faced the challenge of managing the transition to the new administration. His decision to appoint a series of Federalist judges in the final days of his term, known as the “midnight judges,” was a strategic move to ensure that Federalist influence would persist in the judiciary. This action, however, was met with considerable criticism from the incoming Jefferson administration and contributed to ongoing tensions between the two parties.

Adams’ presidency was characterized by both achievements and challenges. His efforts to avoid war with France and his commitment to diplomacy were notable aspects of his leadership. The successful resolution of the Quasi-War through the Treaty of Mortefontaine demonstrated his dedication to preserving peace and protecting American interests. However, his presidency was also marked by contentious domestic policies, including the Alien and Sedition Acts, which contributed to his declining popularity and the growing partisan divide.

The legacy of John Adams’ presidency is complex. On one hand, his commitment to diplomacy and his role in navigating the challenges of international conflict were significant achievements. His efforts to prevent war with France and his strategic decisions during a tumultuous period were important contributions to the early history of the United States. On the other hand, the controversies surrounding the Alien and Sedition Acts, coupled with the polarized political climate of the time, highlighted the difficulties he faced in governing and maintaining party unity.

In retrospect, Adams’ presidency was a period of transition for the young republic. His leadership during a time of international tension, his commitment to the principles of governance, and his role in the development of the American political system left a lasting impact on the nation. Despite the challenges and controversies, Adams’ presidency played a crucial role in shaping the early years of the United States and laying the groundwork for its future development.

Later Years and Legacy (1801-1826)

After leaving the presidency in 1801, John Adams retired to his farm in Quincy, Massachusetts, where he spent the remaining years of his life in relative obscurity. His post-presidency years were characterized by a focus on personal reflection, correspondence, and continued engagement in political and historical discussions. Though he had been out of the public eye, Adams remained a prominent figure in American political life through his extensive correspondence with fellow Founding Fathers, including Thomas Jefferson.

Adams’ retirement was marked by his deepening friendship with Jefferson. Despite their political rivalry, Adams and Jefferson developed a strong bond after their presidencies. Their correspondence, which began in 1812 and continued until their deaths, is considered one of the most significant exchanges between American statesmen. Their letters covered a wide range of topics, including philosophy, history, and reflections on their roles in the American Revolution and the early years of the republic. This correspondence offers valuable insights into their thoughts and the historical context of their time.

In addition to his correspondence, Adams was active in his local community and continued to write about political and historical subjects. He was involved in the development of his hometown, Quincy, and took an interest in local affairs. His later years were also marked by a sense of fulfillment and pride in the accomplishments of his life, despite the challenges he had faced during his presidency.

John Adams passed away on July 4, 1826, the same day as Thomas Jefferson, marking the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. His death on this significant date was seen as a poignant symbol of his lifelong dedication to the cause of American independence and his role in the founding of the nation. Adams’ legacy as a Founding Father, statesman, and advocate for liberty remains deeply respected.

Adams’ contributions to American history are profound. His role in the drafting of the Declaration of Independence, his diplomatic efforts in securing international recognition for the United States, and his presidency all played crucial roles in shaping the early years of the republic. His commitment to the principles of democracy, justice, and governance left an enduring impact on the nation.