In the dusty upper layers of northeastern China’s Nenjiang Formation, twelve isolated but revelatory relics of a lost world have been unearthed—fossilized teeth that once lined the jaws of thunderous herbivores and agile predators of the Late Cretaceous. What appears modest in scale—a mere dozen teeth emerging from a layer scarcely ten centimeters thick—has proven to be a significant addition to our understanding of dinosaur diversity, distribution, and evolution in East Asia. The discovery, recently detailed in Acta Geologica Sinica by Keifeng Yu and colleagues, illuminates a forgotten chapter of prehistory and helps fill one of the most conspicuous gaps in China’s Cretaceous fossil record.

Paleontologist Dr. Wenhao Wu, one of the principal voices behind the study, considers the Songliao Basin—a sprawling sedimentary region in northeastern China—an untapped archive of Earth’s ancient past. “The Songliao Basin,” he says, “hosts a continuous sequence of Late Cretaceous continental strata, making it a geological treasure trove. Yet, in terms of dinosaur fossils, it has remained curiously quiet—especially in the upper layers where many species should have thrived.”

The new findings from the Nenjiang Formation shake up that quiet. Hidden within fine-grained sediments were teeth from at least five distinct dinosaur groups: the ferocious tyrannosaurids, the nimble dromaeosaurines and velociraptorines, the immense titanosaurs, and the ever-evolving hadrosauroids. While tooth fossils lack the grandeur of full skeletons, they serve as surprisingly potent keys to unlocking evolutionary, ecological, and biogeographical secrets—especially when those teeth once tore through prey or ground down tough Late Cretaceous vegetation.

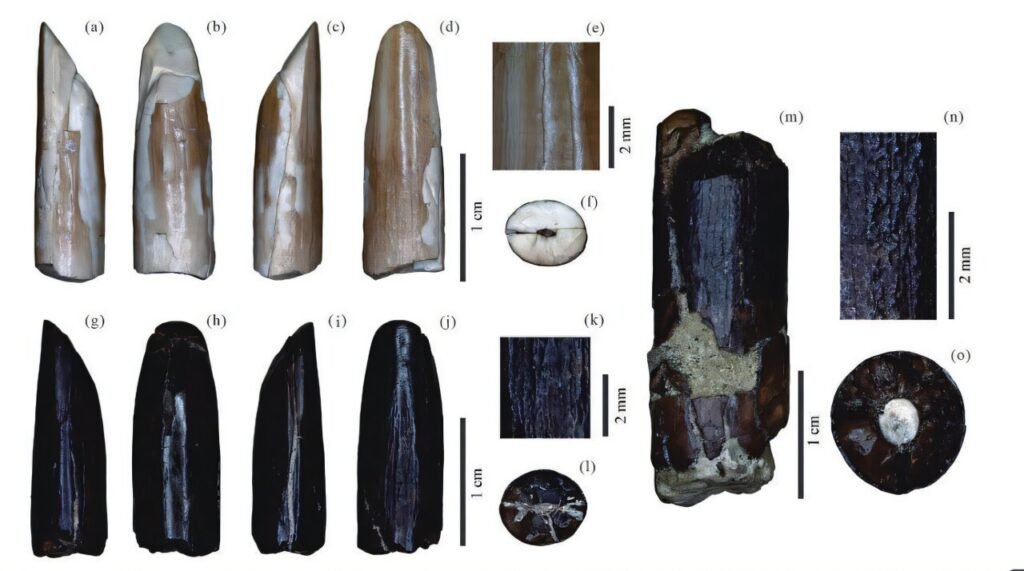

Identifying dinosaurs from teeth alone is notoriously difficult. While mammalian teeth are complex enough to allow for species-level classification, most dinosaur teeth are simpler and more generalized within families. Yet, the research team, through careful morphological analysis, managed to assign the teeth to particular taxa. Among the carnivorous finds, four were theropod teeth—two of them unmistakably from tyrannosaurids. These were powerful, robust teeth with pronounced serrations, built to crush bone and rend flesh. Their chisel-shaped denticles and sheer size left little doubt.

The other two theropod teeth revealed even more intriguing insights. One was linked to Dromaeosaurinae, a subfamily of the famous raptor-like dinosaurs, and the other to Velociraptorinae—a rare find in this part of Asia. These teeth were smaller, more blade-like, and slightly recurved, ideal for slashing attacks rather than brute force. But what made them truly extraordinary wasn’t just their morphology; it was their geography. The velociraptorine tooth represented the first of its kind found in the Nenjiang Formation, and the dromaeosaurine tooth marked a 500-kilometer north-eastern extension of the known range of this group in China. These aren’t just isolated discoveries; they are boundary-pushers that reshape our understanding of where these dinosaurs lived and how they may have moved through ancient ecosystems.

Yet it’s among the plant-eaters that some of the study’s most significant revelations unfold. The bulk of the remaining teeth belonged to herbivorous dinosaurs, including sauropods and hadrosauroids. Among the sauropod teeth, three were classified within the massive clade Titanosauria—a lineage of long-necked dinosaurs that once roamed continents with ponderous grace. Titanosaurs were particularly sensitive to climate, often thriving in warmer low-latitude regions. Their remains are rarely found in cooler or high-altitude environments, making their presence in the Nenjiang Formation both unexpected and groundbreaking.

The Songliao Basin is located at a relatively high latitude, and its climate during the Campanian period—the second-to-last stage of the Cretaceous—would not have been ideal for most titanosaurs. Yet here they were. Their presence in this region doesn’t just stretch their known geographical limits; it challenges long-held assumptions about their habitat preferences and adaptability. It suggests that titanosaurs might have been more resilient and widespread than previously believed.

Even more fascinating are the five teeth attributed to hadrosauroids, a group of duck-billed dinosaurs known for their versatile chewing mechanisms and evolutionary success. The teeth in question bore slightly off-center ridges and only one or two small accessory ridges—a distinctive pattern marking them as non-hadrosaurid hadrosauroids. These primitive members of the hadrosaur family tree were precursors to the later, more specialized duck-bills that would dominate Late Cretaceous herbivore communities across the Northern Hemisphere.

Hadrosauroids, once flourishing across Laurasia and parts of Gondwana, had begun to decline by the end of the Cretaceous. The teeth discovered by Yu and his team are the first non-hadrosaurid hadrosauroid fossils ever found in the Songliao Basin, extending the known range of these dinosaurs and offering a glimpse into their evolutionary arc before their eventual disappearance.

These discoveries are not just about plotting points on a paleogeographic map. They are about understanding the intricate web of dinosaur evolution and extinction in the context of climate, ecology, and environmental change. The Songliao Basin, with its vast and relatively undisturbed sequences of Late Cretaceous rock, offers a rare opportunity to study the final chapters of the dinosaur era from an East Asian perspective—a region often overshadowed by the fossil-rich landscapes of North America and Mongolia.

Indeed, the contrasts are striking. While the Songliao Basin has long been suspected to harbor significant fossil potential, much of the previous dinosaur evidence from this region has come from the lower Quantou Formation, dating to the earlier Cenomanian stage. The upper layers—especially those corresponding to the Campanian—have remained largely unexplored. In contrast, Campanian strata in North America and Mongolia have yielded an abundance of dinosaur fossils, from the elaborate frills of ceratopsians to the stealthy predators of the Gobi Desert.

The Nenjiang discovery narrows that disparity. It shows that East Asia, too, harbored a diverse array of dinosaurs in the Campanian, including taxa never before documented in the region. These teeth, though few and fragmented, speak volumes. They confirm long-held suspicions that much remains buried beneath the surface of Songliao’s sedimentary history—and that China’s Late Cretaceous story is far from complete.

The process of recovering and analyzing these teeth was meticulous. Extracted from a sediment layer no thicker than a paperback book, the fossils were cleaned, photographed, and examined under magnification. Researchers scrutinized each curve, ridge, and denticle, comparing them to known specimens and consulting the latest morphological data to make confident identifications. It’s a reminder that even the smallest fossils, when studied with precision and context, can carry enormous scientific weight.

Moreover, this study opens the door to a flood of future investigations. If twelve teeth can revise our understanding of five major dinosaur groups in one region, what might a more extensive excavation yield? Could more complete skeletons be hidden nearby, waiting for the right conditions and expertise to bring them to light? The Songliao Basin may well become one of the next great frontiers in dinosaur paleontology.

There is also a broader implication. As paleontologists continue to refine the dinosaur timeline and map ancient ecosystems, finds like those from Nenjiang serve as critical benchmarks. They help fill temporal and geographic gaps that are essential for building accurate evolutionary models. They reveal migratory patterns, suggest climatic tolerances, and even hint at how global ecosystems responded to the stresses that would culminate in the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction.

In many ways, the Nenjiang teeth are like missing pages from a once-shattered book, pieced back together to reveal a story more intricate than we imagined. The world of the Late Cretaceous was dynamic, interconnected, and diverse. These teeth are not just the remnants of ancient creatures—they are traces of vanished lives, clues to vanished landscapes, and testimony to Earth’s capacity for both grandeur and loss.

As Dr. Wu and his colleagues continue their work, one thing is clear: the Songliao Basin still holds many secrets. It is a place where bones sleep beneath stone, where history waits in silence, and where even a single tooth can echo across millions of years, whispering of titans and terrors long gone, but not forgotten.

More information: Kaifeng Yu et al, New Dinosaur Teeth from the Upper Cretaceous Nenjiang Formation in Songliao Basin, Northeast China, Acta Geologica Sinica – English Edition (2025). DOI: 10.1111/1755-6724.15288