Long before the pyramids of Egypt rose from the desert sands, before the Great Wall of China traced the edges of empire, there was a land where humanity took its first great leap toward civilization. Between two mighty rivers—the Tigris and the Euphrates—lay a fertile plain known as Mesopotamia, a word that means “the land between rivers.” It was here, thousands of years ago, that the human story transformed forever.

Mesopotamia is often called the “Cradle of Civilization,” and rightly so. In this ancient land, people learned to harness nature, build cities, invent writing, create laws, and gaze toward the stars in search of divine meaning. Here, the first empires rose and fell, the first libraries were built, and the first dreams of progress were born. Every society that came after—Greek, Roman, Persian, and modern—stands on the foundations laid by the people of Mesopotamia.

Yet the story of Mesopotamia is not just one of achievements. It is a tale of struggle and innovation, of floods and famine, of gods and kings, of humanity striving against nature and its own limitations. It is, in every sense, the dawn of civilization itself.

The Gift of the Rivers

Mesopotamia’s destiny was shaped by water. The Tigris and Euphrates rivers flowed from the mountains of Anatolia, winding through what is now modern Iraq, parts of Syria, and Kuwait, before emptying into the Persian Gulf. Between them stretched a vast plain of rich, alluvial soil—dark, fertile, and full of promise.

This land was both generous and cruel. The rivers could bring life through irrigation, but they could also destroy everything through unpredictable floods. Unlike the gentle, predictable Nile of Egypt, the Tigris and Euphrates were wild and temperamental. To thrive here, humans had to learn cooperation, innovation, and resilience.

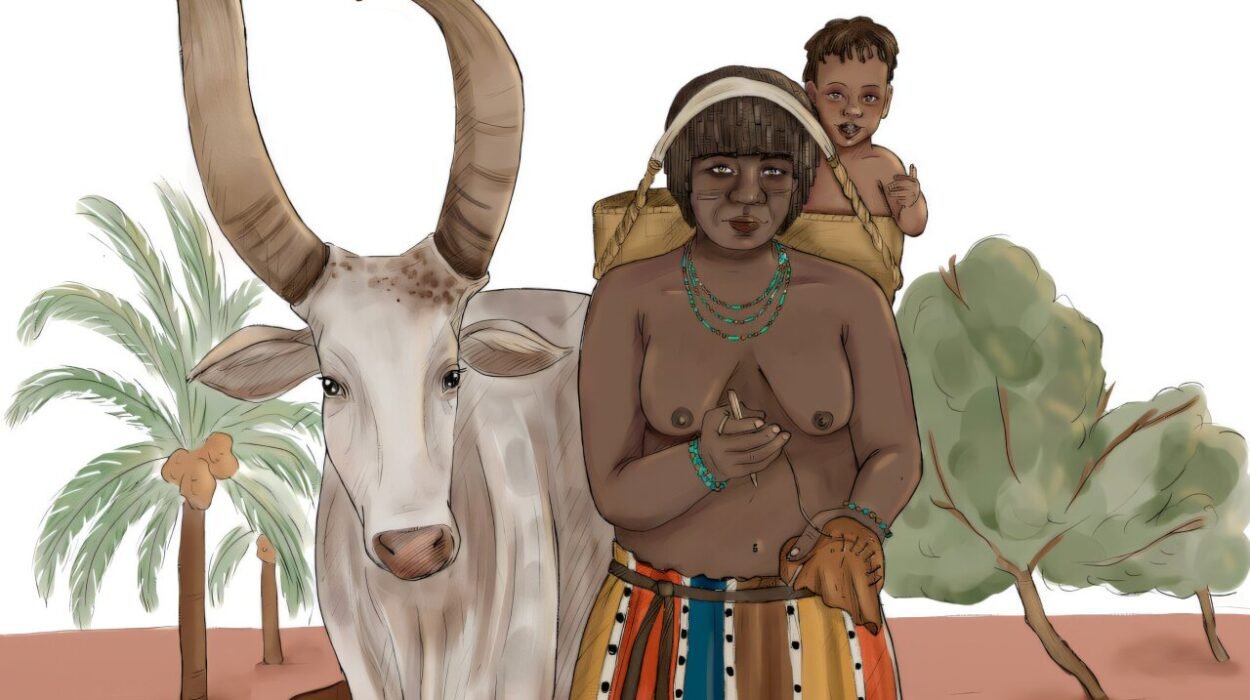

The earliest settlers arrived around 10,000 years ago, drawn by the fertile soil and abundant resources. By 6000 BCE, farming villages dotted the riverbanks. People cultivated barley, wheat, and dates, domesticated sheep and goats, and built irrigation canals to control the flow of water. This mastery over the environment was the first step toward civilization.

In this delicate balance between chaos and control, between flood and drought, humanity discovered its greatest power—the ability to shape the world with intellect and labor.

From Villages to Cities

As agriculture flourished, the population grew. Villages expanded into towns, and towns evolved into cities. By 4000 BCE, the landscape of southern Mesopotamia—known as Sumer—was dotted with the world’s first true urban centers: Eridu, Uruk, Ur, Lagash, and Nippur.

Uruk, in particular, stands as a symbol of this transformation. By 3200 BCE, it was a sprawling city of over 50,000 inhabitants—an astonishing number for its time. Within its walls stood temples, workshops, homes, and marketplaces bustling with trade and energy. It was here that writing was born, art flourished, and organized religion took shape.

Life in these early cities required coordination. The canals had to be maintained, harvests stored, and disputes settled. This gave rise to structured governments, bureaucracies, and leaders who claimed divine authority. Thus, from the fertile chaos of the rivers emerged the first kings.

The rise of the city was the rise of complexity. People began to specialize in trades—pottery, weaving, metalwork, and carpentry. Trade routes expanded, bringing goods from faraway lands: lapis lazuli from Afghanistan, cedar wood from Lebanon, and copper from Oman. For the first time, humanity was no longer confined to survival—it was reaching for progress.

The Invention of Writing

Perhaps the most revolutionary achievement of Mesopotamia was the invention of writing. Around 3200 BCE, Sumerian scribes in Uruk began using pictographs—simple drawings carved into clay tablets—to record transactions and inventories. Over time, these symbols evolved into a system of wedge-shaped marks made with a reed stylus, known as cuneiform.

At first, writing served practical needs—recording grain rations, trade goods, and taxes. But soon, it became a tool for storytelling, governance, and religion. Through writing, kings could issue decrees, priests could record hymns, and poets could preserve epics.

The Epic of Gilgamesh, one of humanity’s oldest known literary works, was written in cuneiform on clay tablets around 2100 BCE. It tells the story of a mighty king’s quest for immortality, a tale filled with gods, friendship, and the fear of death. It is a story not just of a man, but of humanity itself—our eternal search for meaning and our acceptance of mortality.

Writing transformed Mesopotamian society. Knowledge could now be preserved and transmitted across generations. History began not as memory but as record. Civilization had found its voice.

The Rise of Sumerian Civilization

The Sumerians were the first to turn the promise of the rivers into a thriving civilization. By 3000 BCE, they had built a network of city-states, each governed by its own ruler and dedicated to its patron deity. These cities were not just places of residence—they were religious and political centers, reflections of cosmic order on Earth.

At the heart of every Sumerian city stood the ziggurat—a towering temple platform that rose toward the heavens. These monumental structures symbolized humanity’s bridge between Earth and the divine. The gods were believed to reside at the top, where priests offered sacrifices and prayers.

Sumerian religion shaped every aspect of life. The gods controlled natural forces—rain, fertility, storms, and death—and humans existed to serve them. This relationship was one of reverence and fear, for the gods were powerful and often capricious.

Sumerians also made remarkable strides in science and technology. They developed a calendar based on lunar cycles, invented the wheel and the plow, and built some of the earliest irrigation systems. Their mathematical innovations included a base-60 system, which still influences how we measure time today.

Sumer was not a unified kingdom but a constellation of city-states—Uruk, Ur, Lagash, Kish, and others—often at war with one another for dominance. Yet out of this competition came progress, innovation, and a legacy that would shape all of human history.

The First Empires

As the centuries passed, new powers rose to challenge and expand upon Sumerian achievements. Around 2334 BCE, Sargon of Akkad united the Sumerian city-states under one rule, creating the world’s first known empire—the Akkadian Empire.

Sargon was a visionary conqueror. His empire stretched from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean, linking diverse peoples under a single administration. For the first time, Mesopotamia was not a collection of cities but a unified civilization.

The Akkadians adopted Sumerian culture, religion, and writing but gave them new expression in their Semitic language, Akkadian. Under Sargon and his successors, art and literature flourished, and trade expanded across the ancient world.

But empires are fragile things. After two centuries, the Akkadian Empire collapsed—likely due to internal rebellion, invasion, and drought. Yet from its ruins arose new powers, each learning from the last. The Babylonians, Assyrians, and later Chaldeans all inherited and redefined the Mesopotamian legacy.

Each empire added layers to the region’s story: laws, libraries, innovations, and myths that echoed through time.

Hammurabi and the Birth of Law

Among Mesopotamia’s greatest legacies is the idea of law—the notion that human behavior could be governed by a written code rather than the whims of rulers. Around 1754 BCE, King Hammurabi of Babylon created one of the earliest and most comprehensive legal systems in history: the Code of Hammurabi.

Carved into a tall basalt stele, the code contained 282 laws covering everything from trade and property to marriage and crime. Its famous principle—“an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth”—reflected the idea of justice as balance, though punishments often depended on social status.

The Code of Hammurabi was not merely a set of rules; it was a vision of order. It sought to establish fairness in a world of chaos, to give structure to human life. It was also a powerful political tool, portraying the king as a divinely appointed protector of justice.

This concept of law—public, codified, and divine—became the foundation of later legal systems across the world. From Hammurabi’s stone stele, the idea of justice as an institution took root in human civilization.

Babylon: The City of Splendor

After the fall of earlier powers, Babylon rose to become the crown jewel of Mesopotamia. Situated on the banks of the Euphrates, Babylon became synonymous with wealth, culture, and architectural marvel.

Under King Nebuchadnezzar II in the 6th century BCE, Babylon reached its zenith. The city’s massive walls, palaces, and temples inspired awe throughout the ancient world. At its center stood the great Etemenanki ziggurat, believed by some to have inspired the biblical story of the Tower of Babel.

The Hanging Gardens of Babylon—though their existence remains debated—became one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, a symbol of beauty and engineering genius. According to legend, they were built to please the king’s homesick queen, with lush terraces of greenery rising above the desert landscape.

Babylon was also a center of intellectual life. Its astronomers mapped the movements of the stars and planets with astonishing precision, laying the groundwork for both astrology and modern astronomy. Its mathematicians refined geometry and developed methods for predicting eclipses.

More than a city, Babylon was an idea—a vision of human potential, grandeur, and the eternal tension between ambition and humility.

Assyria: The Empire of Power and Iron

To the north of Babylon rose another formidable power: Assyria. If Babylon was a symbol of beauty and intellect, Assyria was the embodiment of strength and domination.

From their capital cities of Ashur, Nineveh, and later Nimrud, the Assyrians built a military machine unlike any before. They perfected iron weapons, siege engines, and cavalry tactics. Their armies were disciplined, relentless, and feared.

But Assyria was more than a warlike state. Its kings were also great builders and patrons of art. The palaces of Nineveh were adorned with vast stone reliefs depicting battles, hunts, and rituals in astonishing detail. King Ashurbanipal established one of the world’s first libraries, collecting thousands of cuneiform tablets on history, literature, and science. Among them was the Epic of Gilgamesh, preserved for millennia.

The Assyrian Empire reached its peak in the 7th century BCE, ruling from Egypt to the Persian Gulf. Yet its brutality also sowed seeds of rebellion. In 612 BCE, a coalition of Babylonians and Medes destroyed Nineveh, ending Assyrian dominance forever.

Still, Assyria’s legacy endured—in architecture, administration, and the very idea of empire.

Gods, Myths, and the Afterlife

Religion was the beating heart of Mesopotamian life. Every event—from harvests to floods, from victories to disease—was seen as the will of the gods. The Sumerians, Akkadians, Babylonians, and Assyrians all shared a pantheon of deities, each embodying natural and cosmic forces.

Anu was the god of the heavens, Enlil the god of air and storms, and Enki (later Ea) the god of wisdom and creation. Inanna (Ishtar to the Akkadians) was the goddess of love and war, a figure both nurturing and fierce.

Temples were the centers of economic and spiritual life, run by powerful priesthoods who mediated between gods and mortals. Festivals, sacrifices, and rituals filled the calendar, reflecting the cyclical nature of life and the struggle to appease divine powers.

The Mesopotamians also developed one of the earliest views of the afterlife—a shadowy realm called the “Land of No Return.” It was not a place of reward or punishment, but a dim existence where souls lived in dust and silence. This somber vision reflected the uncertainties of life in a world governed by capricious gods and fragile prosperity.

Their myths, however, were not mere superstition—they were early expressions of humanity’s effort to understand existence. The stories of creation, the flood, and the struggle between order and chaos found in Mesopotamian literature would echo through later religions and civilizations.

Science and Innovation in the Ancient World

Mesopotamia was not only the birthplace of writing and law—it was also the birthplace of science. Its priests and scholars, while serving religious duties, became the world’s first astronomers, mathematicians, and physicians.

By carefully observing the skies, they charted the motions of stars and planets, predicting seasonal changes vital for agriculture. They divided the circle into 360 degrees, created a 12-month calendar, and established the 24-hour day.

Their mathematical system, based on the number 60, still shapes how we measure time and angles today. Clay tablets reveal calculations of geometry, algebra, and even early trigonometry—astonishing achievements for a civilization so ancient.

Mesopotamian medicine combined empirical observation with spiritual belief. Diseases were thought to result from the anger of gods or demons, but physicians also developed practical treatments—herbal remedies, surgical procedures, and diagnostic methods.

In architecture, they mastered brickmaking and construction, building not only homes but monumental temples, palaces, and walls. Their inventions—the wheel, the sailboat, and the plow—transformed human life forever.

The Legacy That Never Died

By the time Persia conquered Mesopotamia in the 6th century BCE, the great cities of Sumer, Akkad, Babylon, and Assyria had already left their mark upon the world. Yet their influence did not vanish—it was absorbed and carried forward by every civilization that followed.

Greek scholars studied Babylonian astronomy; Roman architects borrowed Mesopotamian techniques; Jewish, Christian, and Islamic traditions inherited Mesopotamian myths and moral concepts. Even our modern systems of law, measurement, and urban planning trace their roots to this ancient land.

Archaeology has resurrected Mesopotamia from the dust. Excavations at Ur, Uruk, and Nineveh have uncovered temples, statues, tablets, and artifacts that reveal a society of extraordinary sophistication. Each discovery adds a new verse to the song of our beginnings.

Lessons from the First Civilization

The story of Mesopotamia is more than a chronicle of kings and conquests—it is a reflection of humanity itself. It shows how fragile civilization can be, yet how enduring human creativity is. The same rivers that gave life could destroy it. The same cities that shone with culture could crumble into ruin.

Yet from every collapse came renewal. From every challenge, innovation. Mesopotamia’s people—farmers, scribes, merchants, priests, and rulers—crafted the blueprint for everything that followed.

Their story is not ancient history alone; it is the first chapter of our shared existence.

The Eternal Echo of Mesopotamia

Today, the land between the rivers is quiet. The great cities of Uruk and Babylon lie in ruins, their ziggurats reduced to mounds of clay and dust. Yet in every written word, every law, every clock that measures our hours, the spirit of Mesopotamia endures.

It lives in our languages, in our ideas of justice and order, in our quest to understand the stars and the mysteries of existence. It whispers through time, reminding us of who we were—and who we became.

Mesopotamia was not merely the beginning of civilization; it was the beginning of humanity’s long dialogue with the world. It was the moment when we ceased to be wanderers and became builders, storytellers, dreamers.

In the shadows of its temples and the lines of its clay tablets, the first light of knowledge flickered. And from that light grew everything that followed—cities, empires, art, science, faith, and the endless human desire to reach beyond the horizon.

Mesopotamia may have fallen, but its soul endures in us. For every time we write, create, govern, or dream of the stars, we are continuing the story that began there—between the rivers, in the cradle of civilization.