Rising from the northern landscapes of Greece, where the horizon meets the clouds in rolling waves of stone, Mount Olympus has long held a place of awe in human imagination. At 2,917 meters (9,570 feet), it is the tallest mountain in Greece, but its significance is not measured in meters alone. For thousands of years, Olympus has stood not only as a physical peak but as a spiritual summit—a bridge between earth and heaven, between the mortal and the divine.

To the ancient Greeks, Olympus was far more than rock and snow. It was the throne of the immortals, the radiant home of the Olympian gods who governed the cosmos. When storms rolled across its summit, they believed Zeus himself was hurling thunderbolts. When the mountain glowed in the golden light of dawn, they imagined the halls of Hera, Apollo, and Athena glittering above the clouds. Olympus was not just a mountain—it was the seat of power, myth, and mystery.

Today, scientists and mountaineers see Olympus as a natural wonder, a national park brimming with biodiversity and geological history. Yet even stripped of myth, the mountain retains its aura of majesty, as if memory itself has left an imprint on the cliffs and valleys. To climb Olympus is to ascend not only a natural peak but a cultural one—a journey into the heart of mythology, history, and human longing for the divine.

The Geography of Olympus

Located near the border of Thessaly and Macedonia, Mount Olympus rises steeply from the Aegean Sea’s coastal plains. Unlike many mountains that stretch into a long chain, Olympus stands apart, a compact and solitary mass, its ridges cutting dramatically against the sky. Its most famous summit is Mytikas, meaning “nose,” which forms the highest point of Greece. Nearby lies Stefani, the “Throne of Zeus,” a jagged crown of rock that dominates the skyline.

Olympus is not one peak but many. Its massif consists of dozens of summits and deep gorges carved by glacial and river erosion. The mountain is composed largely of limestone, which formed under ancient seas before being thrust skyward by tectonic forces millions of years ago. Over time, water carved caves and chasms, creating a labyrinth of stone that adds to its aura of mystery.

The mountain is also a sanctuary for life. Designated Greece’s first national park in 1938 and later recognized as a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve, Olympus shelters more than 1,700 plant species and countless animals, from wolves and deer to eagles and butterflies. Its lower slopes are cloaked in oak and pine forests, while its higher ridges are bare, wind-scoured, and snowbound for much of the year.

Yet, beyond the flora and fauna, Olympus has another presence: the human imagination. Its geography provided a stage, but mythology gave it a soul.

The Birth of a Mythical Home

Why did the Greeks choose Olympus, of all mountains, as the home of their gods? The answer lies partly in its physical dominance. Towering above the plains, shrouded in clouds, Olympus seemed unreachable and mysterious. Its summit was often hidden from sight, reinforcing the belief that mortals could never intrude upon the sacred dwelling of the immortals.

In Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, Olympus is depicted not as a cold, barren peak but as a radiant palace. There, the gods dined on nectar and ambrosia, their laughter echoing through golden halls. Unlike humans, they did not feel wind or rain—the mountain’s peak was bathed in eternal sunshine, untouched by storms that lashed its lower slopes. It was paradise in the sky, a realm of perfection above the chaos of the mortal world.

To the Greeks, this made sense. If gods were immortal, their home must be equally divine, free from decay, suffering, and imperfection. Olympus became the ultimate symbol of separation between gods and mortals: visible yet inaccessible, near yet impossibly far.

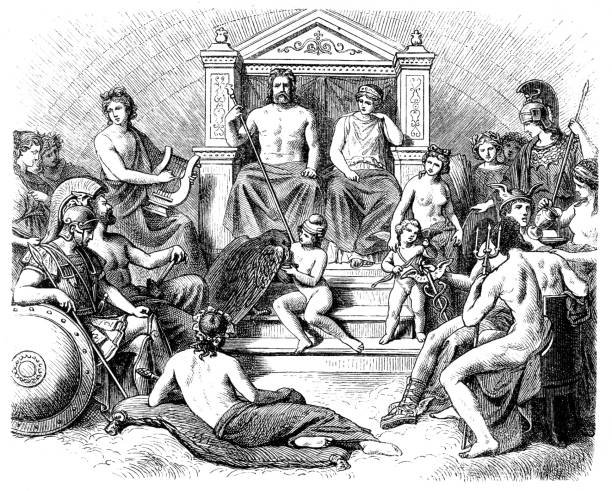

The Olympian Pantheon

Olympus was not home to a single god but to a pantheon of twelve deities, each governing aspects of the universe. At the summit of their hierarchy sat Zeus, the sky-father and wielder of thunder. His throne was said to stand in Stefani, the peak that still bears his name. From there, he ruled the heavens and earth, dispensing justice with both mercy and wrath.

Beside him was Hera, his queen, protector of marriage and family. Athena, born from Zeus’s head, embodied wisdom and war’s strategic side, while Apollo represented light, music, and prophecy. His twin sister, Artemis, ruled the hunt and wilderness, while Aphrodite embodied beauty and love.

The pantheon also included Ares, god of war’s chaos and bloodshed; Demeter, goddess of agriculture and harvest; Hephaestus, the divine craftsman of fire and forge; Hermes, messenger and trickster; Poseidon, master of the seas; and Dionysus, the youthful god of wine, ecstasy, and transformation.

Together, they formed a divine society, with feasts, quarrels, alliances, and betrayals not unlike those of mortals. But unlike mortals, their intrigues shaped the destiny of the world. From their halls on Olympus, they looked down upon heroes and kings, guiding battles, blessing cities, or unleashing disasters.

Olympus in Ancient Religion

For the Greeks, Olympus was both a symbol and a sacred reality. Though no temple was ever built on its summit—perhaps out of reverence, perhaps because it was too remote—the mountain loomed in religious consciousness. Instead, cities built temples and altars at lower altitudes or elsewhere in Greece, believing the gods could descend from Olympus to receive offerings.

At the foot of Olympus stood the ancient city of Dion, a place of great religious importance. Here, festivals and sacrifices were held to honor Zeus and the Olympian gods. Pilgrims gathered to celebrate, pray, and seek divine favor, with the mountain looming above as a silent witness.

Olympus thus became not only a mythic dwelling but a spiritual anchor. The gods were not distant abstractions—they lived just beyond the clouds, watching, intervening, and inspiring. This closeness shaped the Greek worldview, where divine presence was woven into daily life.

Olympus in Myth and Story

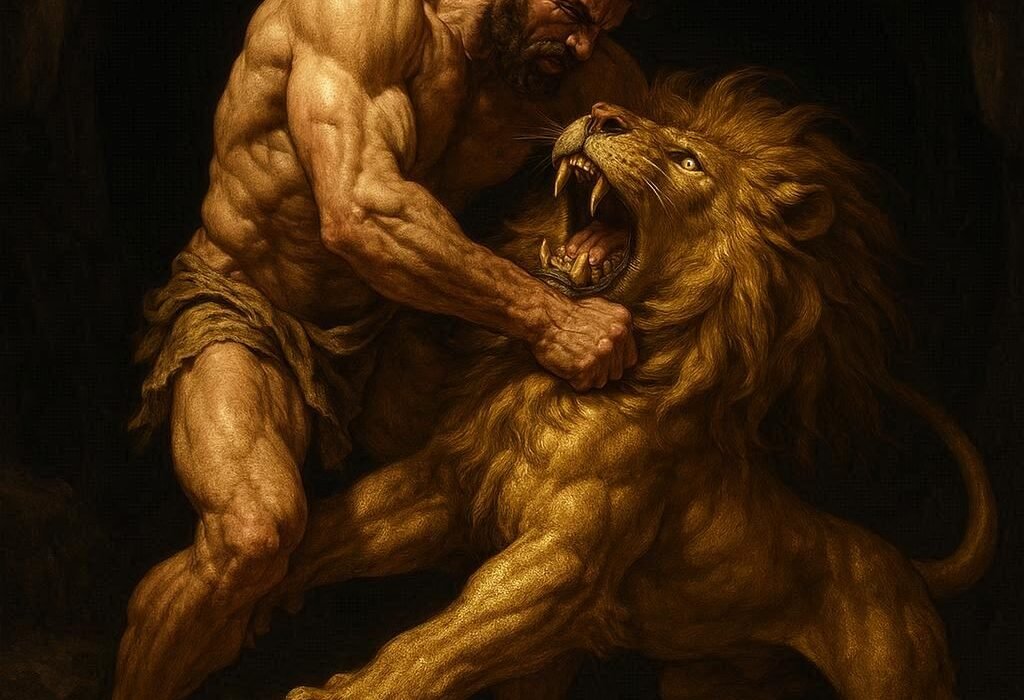

Throughout Greek mythology, Olympus is not just a backdrop but a stage for countless dramas. In the Iliad, the gods debate and argue over the fate of Troy, each taking sides in the great war. Zeus’s thunderbolts shake both heaven and earth, while Hera and Athena conspire to aid their favored heroes.

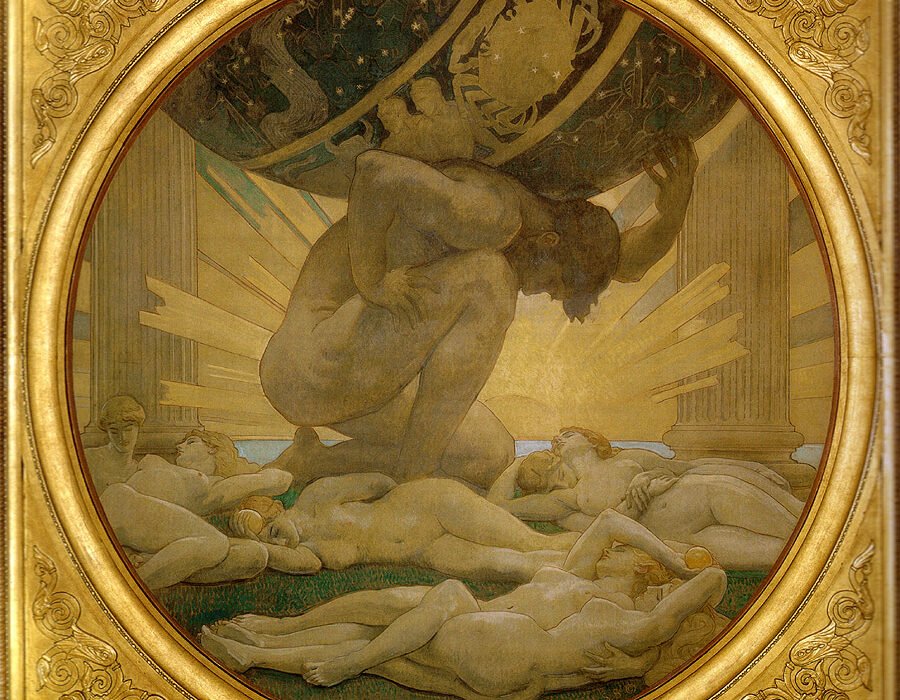

In Hesiod’s Theogony, Olympus becomes the prize of victory after Zeus and his siblings defeat the Titans in the cosmic Titanomachy. With their triumph, they ascend to Olympus, establishing their eternal reign. The mountain thus becomes not only a home but a monument to divine victory and order.

The myths of Olympus also reveal the gods’ very human qualities—jealousy, pride, desire, and anger. This duality, of divine power and human flaw, gave the stories their enduring resonance. Olympus was both a heaven and a mirror of human society, elevated yet relatable.

The Mountain in History and Culture

Even as Greek religion gave way to Christianity, Olympus never lost its hold on the imagination. Byzantine monks settled on its slopes, building monasteries and hermitages in the hidden valleys. To them, the mountain remained sacred—not as the seat of pagan gods but as a place of spiritual solitude and divine closeness.

In modern times, Olympus has become a national symbol of Greece, representing both natural beauty and cultural heritage. Every year, thousands of climbers and hikers ascend its trails, seeking not only adventure but connection with a mountain steeped in myth. Reaching Mytikas is not just a physical achievement but a pilgrimage to the roof of Greece, where sky and stone meet in silent majesty.

The mountain has also inspired poets, artists, and thinkers across centuries. From Pindar and Euripides in antiquity to modern writers, Olympus continues to symbolize the human desire to reach higher, to touch the divine, and to bridge the gap between earth and heaven.

Olympus in Science and Exploration

Though steeped in myth, Olympus is also a subject of science. Geologists study its limestone layers, tracing their origins back to shallow seas of the Mesozoic era. Botanists explore its flora, finding alpine flowers that survive against icy winds. Ecologists examine its ecosystems, where Mediterranean and Balkan species mingle in unique diversity.

Climbers and explorers, too, have left their mark. The first recorded ascent of Mytikas occurred in 1913, led by Swiss climbers and a local guide. Since then, Olympus has become a destination for mountaineers worldwide, its trails offering both challenge and wonder.

Yet despite its accessibility, the summit often remains shrouded in cloud—a reminder of the mystery that has always surrounded it. For even when reached, Olympus resists full possession, as if guarding its secrets for eternity.

The Symbolism of Olympus

Beyond its physical and mythological presence, Olympus represents something deeper: the human quest for transcendence. Mountains across cultures—Everest in Nepal, Kailash in Tibet, Fuji in Japan—have been seen as sacred, places where the divine dwells. Olympus is the Greek expression of this universal impulse, the belief that the highest peaks bring us closer to the gods.

In this sense, Olympus is not only a place but an idea. It is the dream of perfection, a realm untouched by decay, a height beyond the reach of ordinary life. It is the symbol of aspiration, reminding us that even in the mortal world, we can imagine the eternal.

Olympus Today: Between Myth and Reality

Today, Mount Olympus stands at the intersection of past and present, myth and reality. Hikers who climb its trails walk through forests where Zeus was once believed to hurl thunderbolts. Botanists studying its wildflowers trace the same paths where poets once envisioned the footsteps of the gods. The mountain is alive with dual meanings—scientific and spiritual, earthly and mythic.

For Greece, Olympus is both heritage and hope. It is a reminder of the power of myth to shape culture, and of the power of nature to inspire reverence. For the world, it remains one of the most famous mountains, not because of its height but because of its story.

To gaze upon Olympus is to see more than stone—it is to glimpse the dreams of a civilization, the laughter of gods in golden halls, and the eternal pull of humanity to climb higher, to seek meaning, to imagine a home among the clouds.

The Eternal Mountain

In the end, Mount Olympus is not only about Greece, mythology, or even nature. It is about the enduring human need to place meaning in the world around us. Olympus gave the ancient Greeks a home for their gods, but it also gave them a vision of order, beauty, and transcendence.

Today, long after the last sacrifice was made at Dion, Olympus continues to inspire. Its peaks still pierce the sky, its forests still whisper in the wind, its legends still echo in art and literature. It stands as both a natural monument and a cultural one—a mountain that carries the weight of history, myth, and imagination.

To call Olympus the “home of the gods” is to honor not only the myths of the past but the eternal human longing for the divine. The mountain rises, immutable and eternal, reminding us that even in a world of science and reason, there is still room for awe, wonder, and the dream of immortality.