Buried beneath the dusty plains of southeastern Turkey, at the archaeological site of Başur Höyük, lies a mystery that is rewriting what we thought we knew about the origins of inequality in human societies. There, in graves dating back over five thousand years, teenagers—some scarcely older than twelve—were laid to rest with swords of bronze, glittering ornaments, exotic beads, and signs of deliberate violence that hint at ritual sacrifice. What makes this discovery extraordinary isn’t just the luxury of their burials. It’s the profound and unsettling question it raises: how could a world so young already be so unequal?

A sweeping international collaboration, involving institutions such as University College London, the University of Central Lancashire, and Ege University, has pieced together this puzzling narrative. Drawing from archaeology, genetics, isotopic chemistry, and forensic anthropology, their research challenges the long-held belief that structured social inequality emerged only after the rise of states, kings, and bureaucratic governance. Instead, the evidence from Başur Höyük tells a different story—one in which power and privilege appeared first not in the palaces of rulers, but in the graves of children.

Traditional archaeology has often told a linear story of civilization. It begins with egalitarian villages—peaceful, modest communities where people shared and survived together. Over time, according to this narrative, these villages grew into cities. Cities birthed elites, bureaucracies, and rulers—bringing with them the earliest class divisions and power structures. Monumental architecture, written law codes, and rich tombs in southern Mesopotamia were taken as markers of this grand transition from equality to hierarchy. Başur Höyük disrupts this script entirely.

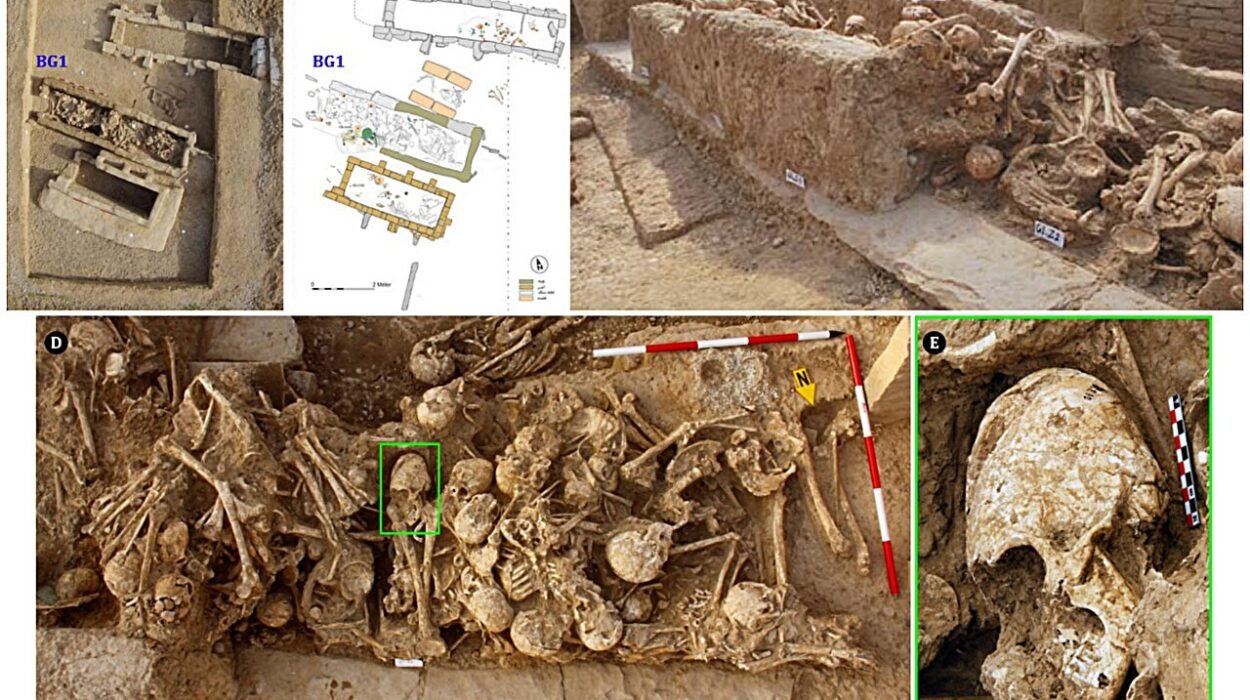

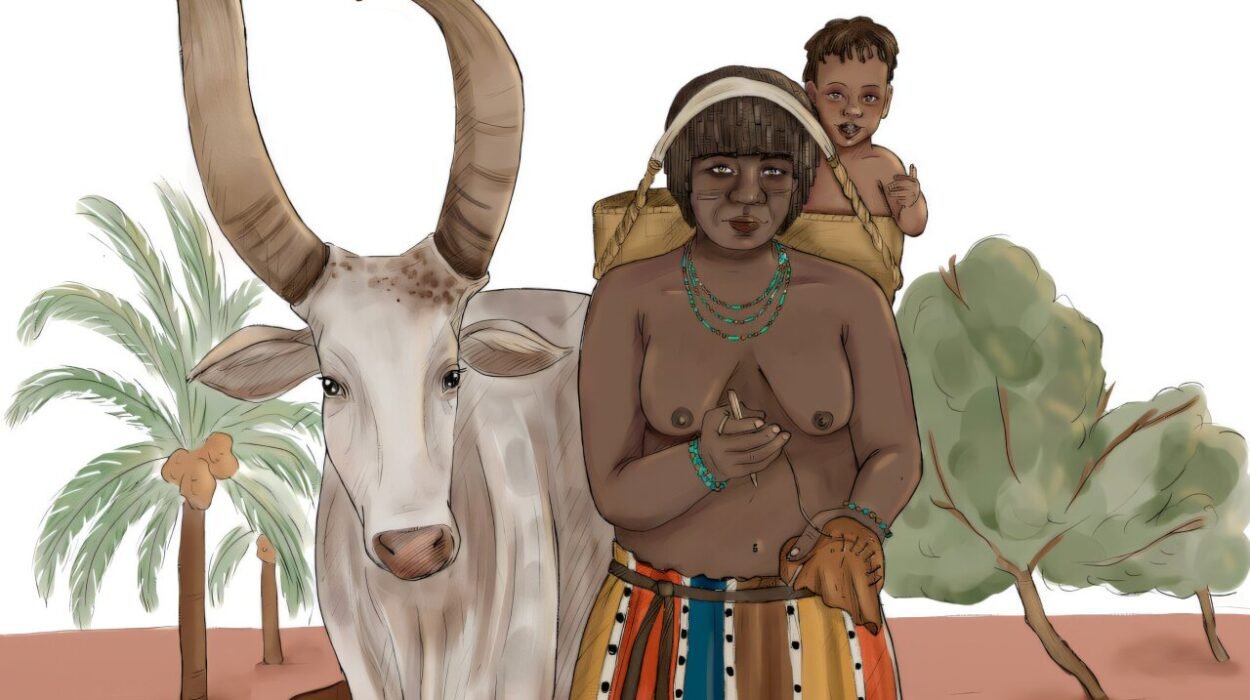

Dated between 3100 and 2800 BCE, the cemetery at Başur Höyük sits not in the heartland of early Mesopotamian civilization but on its rugged northern periphery. The site consists of 18 graves—some simple pits, others built of stone slabs in cist formation—holding both individual and multiple interments. The difference between them is striking. While some burials are modest, others brim with wealth: bronze daggers, silver beads, finely crafted ornaments, and garments woven with materials from distant lands. And almost without exception, the central figures in these opulent graves are adolescents—boys and girls between 12 and 16 years of age.

This in itself is unusual. Across early cultures, elaborate burials are typically reserved for adults—elders, warriors, religious leaders, or rulers. To find such riches concentrated around teenagers suggests that something very different was at work in Early Bronze Age Anatolia.

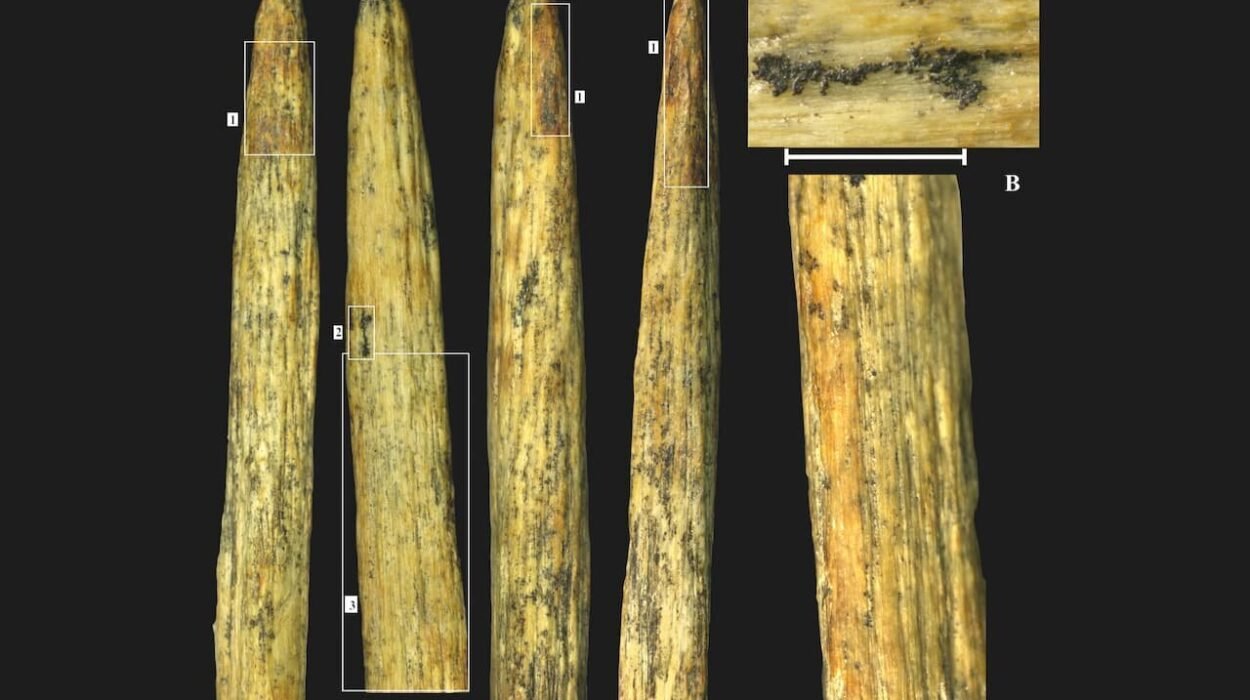

The research team employed an impressive suite of techniques to decode the mystery. Ancient DNA analysis revealed that these lavishly buried adolescents were not close relatives. There were no signs of noble lineages or ruling families. Isotopic testing, which examines chemical signatures in bones and teeth, indicated that many of them had grown up far from Başur Höyük—possibly even outside the region entirely. Some were migrants, others perhaps captives. Moreover, forensic analysis revealed signs of sharp-force trauma on certain individuals, consistent with ritual killing—a practice seen in other ancient societies where human life was sacrificed to serve the dead in the afterlife.

But perhaps most revealing was the pattern of burial architecture and ornamentation. The stone cist graves, especially those containing weapons and jewelry, were spatially clustered and organized. Richly adorned adolescents were placed in prominent positions, often surrounded by less well-equipped individuals in more subordinate postures—lying at the feet or along the margins of the grave. The implication is chilling: these may have been sacrificial attendants, buried to serve their adolescent masters beyond death.

What can we make of this? If these adolescents were not royals, if they held no inherited position, and if they died before adulthood, how did they come to command such status in death? The researchers suggest several possibilities. One theory is that Başur Höyük reflected an age-based social structure—where youth, rather than lineage or adult achievement, conferred special meaning. In such a society, adolescence may have been seen as a liminal phase, a sacred time of transformation worthy of ceremonial reverence. Alternatively, the burials could represent a symbolic or ritual cult centered on youthful vitality—where young people were venerated in ways disconnected from political authority.

Either way, the findings are revolutionary. They suggest that social inequality may have emerged first not in the boardrooms of ancient administrators, but in the ceremonial and spiritual realm. Before states and kings carved power into stone, before scribes penned the rules of dynasties, there may have been inequality born of belief, not bureaucracy.

This turns the conventional model of social evolution on its head. For decades, scholars have debated the origins of inequality. Was it agriculture, with its surpluses and storerooms? Was it private property? Was it war, or religion, or trade? The discoveries at Başur Höyük imply another layer: that symbolic inequality—the power to inspire awe, receive sacrifice, or command elaborate funerary rites—could predate material inequality and formal hierarchies. It may have been through ritual, not rule, that human societies first learned to separate themselves into ranks.

The implications extend far beyond ancient Anatolia. If ceremonial inequality existed centuries before state formation in this region, might similar processes have occurred elsewhere? Could the seeds of social hierarchy lie not in laws and cities, but in more intangible human impulses—the desire to honor, to worship, or to distinguish?

Moreover, the fact that the adolescents buried at Başur Höyük were not related, and in some cases not even local, raises unsettling questions. Were these children brought from afar to be sacrificed? Were they chosen, or captured? Did their deaths reflect power held by a priesthood or cult that has otherwise vanished from the archaeological record?

And what of the evolution of these customs? Later in the Bronze Age, adult burials across the region begin to mirror the adornments and practices seen at Başur Höyük—wealthy grave goods, sacrificial attendants, and elaborate tomb construction. Could this reflect a transition, where symbols of honor once reserved for youth were appropriated by adults who had gained political and economic power? In this light, the rise of dynasties and elite lineages may not have created inequality, but rather inherited and institutionalized earlier forms of ritual distinction.

The authors of the study caution against drawing overly definitive conclusions. The full nature of the rituals at Başur Höyük remains obscure. The dead speak in fragments: beads, bones, and blades. Their voices have been buried for millennia. But one thing is increasingly clear—inequality did not simply emerge when humans built cities. It may have been born in the earliest places where we gathered to bury our dead, and to tell stories about what it meant to live, and to matter.

In reinterpreting the past, the study does more than update our timelines. It forces us to reconsider the origins of status and power—not as inevitable consequences of civilization, but as complex, sometimes contradictory choices made by human communities. At Başur Höyük, those choices involved children, sacrifice, and a worldview that remains tantalizingly out of reach.

Ultimately, the graves at Başur Höyük reflect more than funerary practices—they reflect a worldview. One in which death was a stage for performance, where the lines between reverence, violence, and inequality were already being drawn in adolescence. In these silent tombs, we glimpse a society testing the boundaries of status, value, and humanity. And in doing so, we begin to understand that the roots of our own social hierarchies may lie not in the grand halls of ancient kings—but in the intimate, ritualized choices of communities long lost to time.

More information: David Wengrow et al, Inequality at the Dawn of the Bronze Age: The Case of Başur Höyük, a ‘Royal’ Cemetery at the Margins of the Mesopotamian World, Cambridge Archaeological Journal (2025). DOI: 10.1017/S0959774324000398