The story of the Tower of Babel is one of the most iconic tales in ancient literature. Told in the eleventh chapter of the Book of Genesis, it describes a united humanity building a colossal tower that would reach the heavens, only for God to intervene, scatter the people, and confound their language. For centuries, this brief biblical account has inspired theological debate, artistic depictions, and archaeological quests. But beneath the surface of this myth lies a far richer story—one of empire, identity, linguistics, and the eternal tension between human ambition and divine order.

The real story behind the Tower of Babel is not just a tale of bricks and hubris. It is a tapestry woven from the histories of Mesopotamia, the myths of Sumer and Babylon, the shifting sands of linguistic evolution, and the deep psychological imprint of the desire to transcend human limits. This is a story that begins not only in the pages of Genesis, but in the mudbrick ziggurats of ancient Iraq, in the cuneiform tablets buried beneath centuries of dust, and in the collective memory of a civilization that sought to understand its place in the cosmos.

The Biblical Account: A Short but Potent Narrative

The Tower of Babel narrative, as found in Genesis 11:1–9, is remarkably concise. In just nine verses, we are told that humanity, speaking a single language, migrated eastward and settled in the land of Shinar. There, they decided to build a city and a tower “with its top in the heavens,” using brick and bitumen. Their goal was to “make a name” for themselves and avoid being scattered across the earth.

But God descended to observe their construction. Troubled by their unified purpose and linguistic uniformity, He confused their language so they could no longer understand one another, and scattered them across the earth. The city was called Babel, “because there the Lord confused the language of all the earth.”

The power of this story lies in its brevity. It encapsulates a profound theological message: that human pride and ambition, when unmoored from divine guidance, lead to fragmentation. Yet this message also raises intriguing questions. Why did God fear a unified humanity? What kind of tower were they building? Where is Shinar, and what was Babel? Was there a real structure that inspired this legend?

To find answers, we must journey back to ancient Mesopotamia—the cradle of civilization.

Shinar and the Shadow of Babylon

The “land of Shinar” in Genesis is widely understood to refer to ancient Mesopotamia, specifically the region known as Sumer and later as Babylon. This fertile plain between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers was home to some of humanity’s earliest cities, writing systems, and monumental architecture. Among these cities, none was more famous—or infamous—than Babylon.

Babylon was more than a city. It was an idea, a symbol of empire, cultural fusion, and divine defiance. Founded as early as the 19th century BCE and rising to prominence under Hammurabi, Babylon became the beating heart of Mesopotamian civilization. Its towering ziggurat—known in Akkadian as Etemenanki, meaning “House of the Foundation of Heaven and Earth”—was believed by many scholars to be the historical basis for the Tower of Babel.

This great ziggurat, dedicated to the god Marduk, stood within the city’s sacred precinct and may have risen nearly 300 feet high. Constructed of sun-dried bricks and bitumen—just as described in Genesis—it was a seven-tiered step pyramid that sought to connect heaven and earth, man and deity. To the people of Babylon, it was a bridge to the divine. To the biblical authors, it may have represented something far more troubling: an audacious attempt to usurp heaven’s authority.

The Ziggurat: Humanity’s Stairway to the Gods

To understand why the biblical narrative paints the tower in such ominous tones, we must explore the role of ziggurats in Mesopotamian society. These were not simply tall buildings. They were sacred mountains, architectural expressions of cosmic order, and places where heaven and earth met. Each ziggurat was part of a temple complex and served as the dwelling place of a city’s patron deity.

The ziggurat at Babylon, Etemenanki, was dedicated to Marduk, the chief god of the Babylonian pantheon. According to Babylonian texts, this tower was not just an object of religious reverence—it was a center of political identity. The construction and maintenance of the ziggurat symbolized a king’s legitimacy, his divine favor, and his role as a mediator between gods and men.

In this context, the building of the Tower of Babel can be seen as a metaphor for imperial ambition. The people are not merely erecting a tall structure; they are trying to create a unified world under a single language, a single authority, and a single ideology. It is no coincidence that Babel sounds like Babylon—a city that, in the biblical imagination, comes to symbolize human arrogance, idolatry, and opposition to God.

Language as a Tool of Empire—and Resistance

One of the most striking aspects of the Tower of Babel story is the emphasis on language. The people originally “had one language and the same words.” Their unity in speech enabled them to coordinate their efforts and aspire to greatness. But it also made them a threat. God’s response—to confuse their language—introduces not only divine intervention, but also the birth of linguistic diversity.

From a historical perspective, language has always been a tool of empire. The imposition of a single language over diverse peoples is a hallmark of centralized power. The Akkadian Empire, the Assyrians, the Persians, and later the Romans all promoted official languages to unify their realms. The biblical narrative reflects this reality, recognizing both the power of linguistic unity and the danger of its misuse.

But the confusion of language is not merely punitive. It is also a creative act. In scattering the people and multiplying their tongues, God introduces diversity, decentralization, and cultural pluralism. The Tower of Babel is not just the origin of different languages—it is the origin of nations, of unique worldviews, of the mosaic of human civilization.

Echoes of Babel in Other Ancient Myths

The story of a great tower reaching the heavens is not unique to the Bible. Throughout the ancient world, similar motifs emerge—stories of human pride, divine punishment, and the division of peoples. These parallels suggest that the Tower of Babel narrative is part of a broader mythological tradition.

In Sumerian literature, for example, we find the tale of Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta. In this story, the king of Uruk prays for a time when all people will speak one language. The text also describes the construction of a great temple and the use of brick and bitumen—strikingly similar to the Babel account. Although this Sumerian tale predates Genesis by centuries, it contains thematic echoes that suggest a shared cultural memory.

Similarly, in the Epic of Gilgamesh, the gods punish human pride and ambition. In Greek mythology, the myth of Icarus—who flies too close to the sun—captures the same warning against overreaching. These stories, across time and culture, reflect a deep human anxiety: that our greatest achievements may become our downfall if we lose sight of humility.

The Historical Fall of Babylon and Its Symbolic Rebirth

Babylon’s legacy did not end with the collapse of its empire. In the Hebrew Bible, Babylon becomes a symbol of oppression, idolatry, and divine judgment. The Babylonian exile, during which the Jews were forcibly relocated to Babylon in the 6th century BCE, left a deep scar on the Jewish psyche. The memory of that exile colored how later biblical writers viewed Babylon—and, by extension, the Tower of Babel.

In the Book of Revelation, Babylon is resurrected as a metaphor for Rome, the decadent and persecuting power of the time. “Babylon the Great” becomes the harlot who seduces kings and merchants, only to be destroyed by divine wrath. In this apocalyptic vision, the ancient tower becomes a symbol of everything that opposes God’s kingdom.

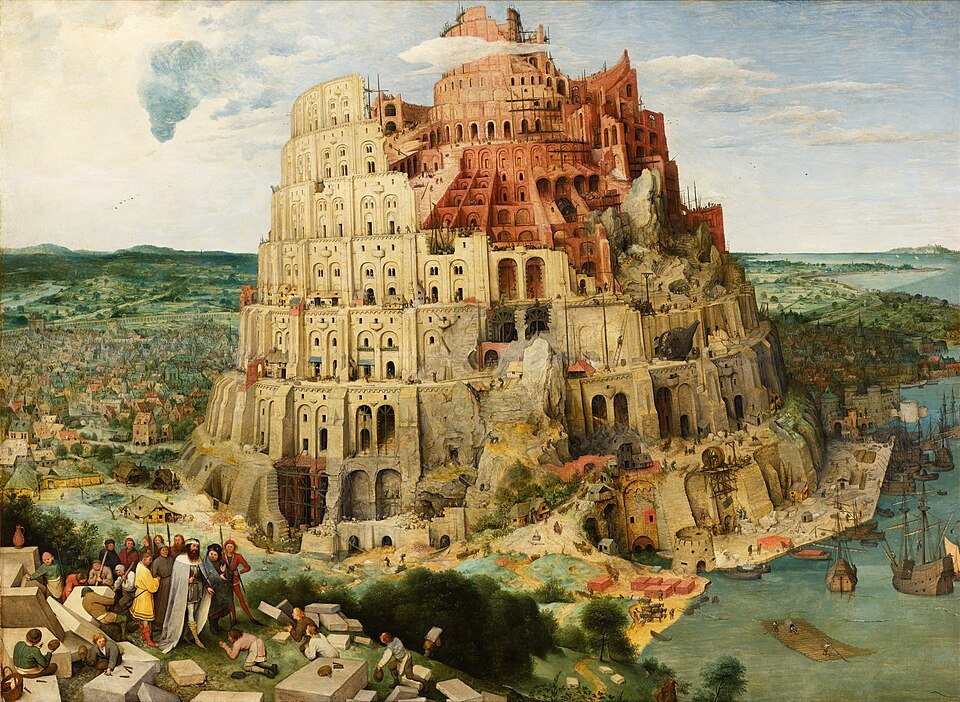

Yet Babylon also fascinated later thinkers. In medieval Europe, the Tower of Babel inspired painters and scholars. In Renaissance art, it was a favorite subject—depicted as a spiraling skyscraper of Gothic arches and biblical drama. For Enlightenment thinkers, Babel became a puzzle of linguistics, a quest to recover the “original language” lost in divine confusion. For modern writers, it is a metaphor for cultural fragmentation and the limits of human understanding.

The Linguistic Legacy: From Babel to Babylonian Cuneiform

The Tower of Babel myth sparked centuries of speculation about the origin of languages. Medieval scholars believed that Hebrew was the original tongue, and that other languages were corrupted branches. The rise of comparative linguistics in the 18th and 19th centuries challenged this view. Scholars began to trace language families, reconstruct proto-languages, and uncover the deep structures that connect speech across cultures.

One of the most astonishing discoveries was the decipherment of cuneiform—the wedge-shaped script of ancient Mesopotamia. Beginning in the 19th century, archaeologists unearthed thousands of clay tablets in cities like Nineveh, Uruk, and Babylon. These texts revealed the richness of Sumerian, Akkadian, and Babylonian culture. They also illuminated the real tower projects undertaken by kings, including Etemenanki.

The decipherment of cuneiform turned the myth of Babel on its head. Where once there was confusion, now there was understanding. The recovery of ancient languages opened a new window into the past, allowing us to see the world that inspired the biblical authors.

A Tower of Memory and Meaning

So what, ultimately, is the real story behind the Tower of Babel? It is a myth rooted in history, a parable drawn from architecture, language, and empire. It reflects the real ziggurats of Mesopotamia, the political ambitions of Babylonian kings, and the theological concerns of ancient Israel.

It is also a mirror—a way of seeing ourselves. The story of Babel is about more than bricks and divine wrath. It is about our desire to unify, to reach higher, to transcend the boundaries of earth and language. It warns of the dangers of pride, yes, but it also celebrates the richness of diversity. It explains the birth of nations, the origins of culture, and the deep mystery of language.

In every age, Babel has been reinterpreted. To the medieval theologian, it was a cautionary tale. To the Renaissance artist, a subject of wonder. To the modern historian, a bridge to the ancient past. And perhaps, to us today, it is a reminder: that in our efforts to build towers—of technology, of knowledge, of ambition—we must not lose sight of our shared humanity.