Since the dawn of human thought, we have gazed upward and asked questions that reach beyond the stars. What is the universe? Where does it end? Does it curve back on itself, or does it stretch into infinity? These are not just abstract philosophical musings—they touch the deepest aspects of human existence. To ask about the shape of the universe is to ask about the structure of everything that has ever been, about the architecture of reality itself.

For most of history, such questions seemed impossible to answer. The stars appeared fixed on the dome of the sky, giving ancient observers the impression that they lived at the center of a finite, spherical cosmos. Over the centuries, that view expanded—from Aristotle’s crystalline spheres to Newton’s infinite space, and finally to Einstein’s dynamic universe, capable of stretching, curving, and evolving.

Today, cosmologists pursue one of the most profound mysteries in all of science: What is the shape of space? Is the universe flat like a sheet, curved like a sphere, or shaped in some unimaginable way? The answer is not a matter of mere geometry—it determines the destiny of the cosmos. It decides whether space will expand forever, collapse into itself, or curve endlessly in a cosmic loop.

The Geometry of the Infinite

To understand what “the shape of the universe” means, we must first grasp the concept of spacetime. Einstein’s theory of general relativity, formulated in 1915, revolutionized our perception of reality. It showed that space and time are not passive backgrounds on which events unfold, but active, flexible entities that can bend, stretch, and warp in response to matter and energy.

Mass and energy tell spacetime how to curve, and that curvature tells matter how to move. Gravity, in this view, is not a force but the effect of this curvature. A planet orbits the Sun not because it is “pulled” by an invisible force, but because the Sun’s mass warps spacetime, creating a natural path that the planet follows.

If matter and energy can curve spacetime locally, what about the universe as a whole? Does all the matter in existence bend the grand fabric of the cosmos? The answer depends on the total amount of mass and energy it contains. The geometry of the universe is dictated by its density—specifically, the balance between its actual density and a critical value determined by the laws of relativity.

If the universe’s density exceeds this critical value, gravity will cause space to curve inward, giving the universe a closed, spherical shape. If the density is lower, space will curve outward, producing an open, saddle-like geometry. And if the density is precisely equal to the critical value, space will be perfectly flat.

This triad—closed, open, flat—represents the three fundamental possibilities for the shape of space. But as we shall see, the story is far more intricate, and the universe may hold surprises beyond even these elegant options.

The Spherical Universe: A Cosmos That Bends Back

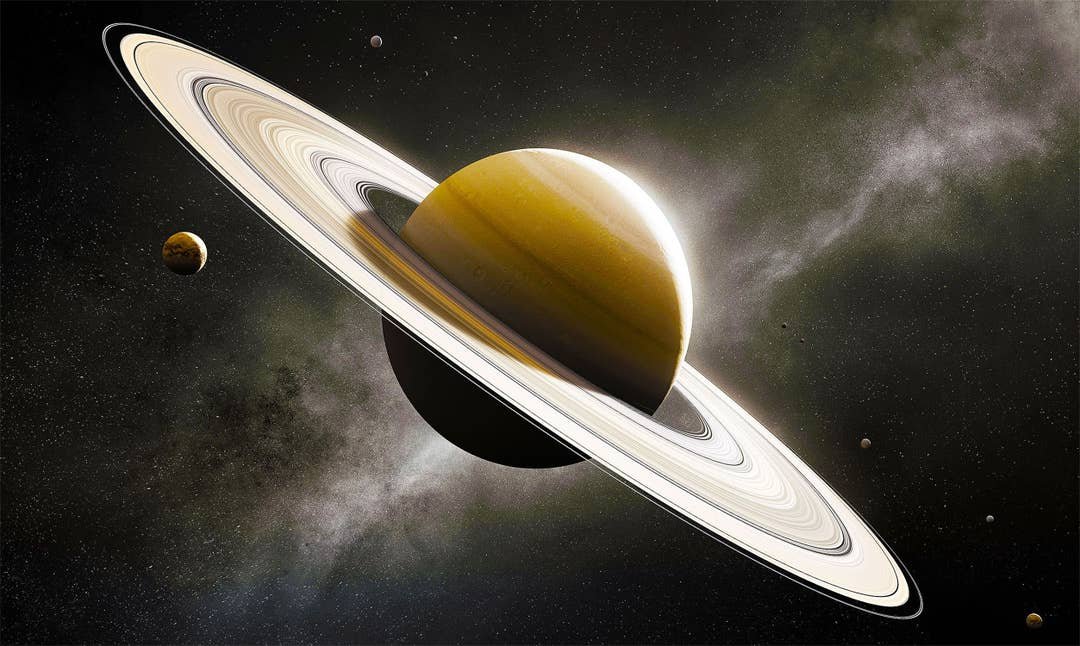

Imagine standing in a vast desert, seeing no edge, only the curvature of the horizon. Now extend that concept to three dimensions. A closed universe is one in which space curves back on itself like the surface of a sphere, but in higher dimensions. You could travel in a straight line forever and eventually return to your starting point—not because space ends, but because it wraps around.

This model has deep philosophical appeal. It gives the universe a finite volume but no boundary, just as Earth’s surface is finite yet unbounded. It also has cosmic consequences: a closed universe contains enough mass to eventually halt its expansion. After billions of years, gravity would overcome the momentum of the Big Bang, slowing the galaxies until they stopped, then drawing them back together in a colossal collapse known as the Big Crunch.

This cyclical vision once fascinated scientists and philosophers alike. It suggests a universe that breathes—expanding, collapsing, and perhaps rebirthing itself in eternal rhythms. The Hindu concept of cosmic cycles, the Stoic “ekpyrosis,” and certain modern cosmological models all echo this idea.

But there is a catch. Observations show that the universe’s expansion is not slowing—it’s accelerating, driven by a mysterious force known as dark energy. This discovery, made in the late 1990s, cast doubt on the closed model. Unless dark energy changes its nature over time, the universe will not recollapse. Still, the possibility of a curved, finite universe remains mathematically viable and philosophically alluring.

The Hyperbolic Universe: A Cosmos of Infinite Saddle

Now imagine a surface shaped like a saddle—curving upward in one direction and downward in another. This is the geometry of an open universe, one with negative curvature. In such a cosmos, parallel lines diverge, and the angles of a triangle add up to less than 180 degrees.

An open universe has too little matter to stop its expansion. It will grow forever, with galaxies receding faster and faster into the void. Over unimaginable timescales, stars will die, galaxies will fade, and the universe will approach a state of cold, dark emptiness—a “heat death” where energy is evenly spread and no further work can be done.

This vision may seem bleak, yet it carries a strange beauty. The open universe represents endless possibility, an infinite cosmos that never repeats, never closes. In such a reality, space has no edge or center—it simply is, boundless and eternal.

Mathematically, open universes arise naturally from Einstein’s equations when the density of matter and energy falls below the critical threshold. Observations of the cosmic microwave background—the faint afterglow of the Big Bang—allow cosmologists to measure this curvature with exquisite precision. What they find suggests something remarkable: the universe is astonishingly close to flat, but if it does curve, it might curve ever so slightly outward, like a vast, cosmic saddle.

The Flat Universe: Geometry of Perfection

The simplest and, according to current evidence, the most accurate description of our cosmos is that it is flat. In a flat universe, Euclidean geometry—the geometry you learned in school—holds true. Parallel lines remain parallel forever, and the angles of a triangle add up to exactly 180 degrees.

This flatness implies that the total energy density of the universe equals the critical density, a balance so precise it seems almost miraculous. Why should the universe be tuned so perfectly? A slight deviation at the beginning of time would have led to drastically different outcomes—either a rapid collapse or an uncontrolled expansion.

The answer may lie in a revolutionary idea known as cosmic inflation. Proposed in the 1980s by physicist Alan Guth and refined by others, inflation suggests that a fraction of a second after the Big Bang, the universe underwent an episode of exponential expansion—growing by a factor of at least 10³⁰ in less than a trillionth of a second.

This inflationary burst would have stretched any initial curvature to near-flatness, much as blowing up a balloon smooths its surface. The observable universe, therefore, may appear flat not because it truly is across all scales, but because we can only see a small, smoothed-out patch of a much larger cosmos.

Measuring the Shape of the Universe

How do we know whether space is curved? The key lies in observing how light travels across vast distances. In a curved universe, light rays that start parallel will either converge (in a closed universe) or diverge (in an open one). By measuring the apparent sizes of distant objects, cosmologists can detect these subtle effects.

The most powerful tool for this is the cosmic microwave background (CMB)—the afterglow of the Big Bang, now cooled to just 2.7 degrees above absolute zero. The CMB is not uniform; it contains minute temperature fluctuations that encode information about the early universe’s geometry.

In 2003, NASA’s WMAP satellite provided the first detailed map of these fluctuations, followed by the European Space Agency’s Planck mission in 2013. The results were striking: the universe appears flat to within a margin of 0.4%. That means if there is curvature, it’s so subtle that even across the observable universe—93 billion light-years in diameter—it would be nearly imperceptible.

However, “flat” does not necessarily mean infinite. Just as the surface of a cylinder can be flat in one direction but loop around in another, space might have a topology more complex than simple geometry implies. It could wrap around in ways that allow light to circle the cosmos and return from another direction—a concept that hints at a finite but unbounded universe.

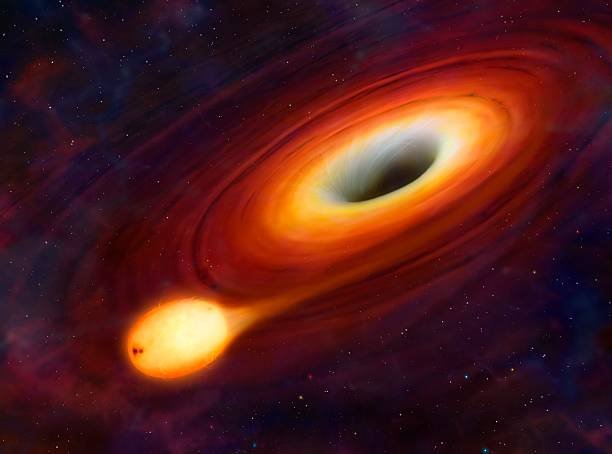

Beyond Geometry: The Role of Dark Energy

The shape of space is not static; it evolves with time. Einstein’s equations reveal that the geometry of the universe depends not only on its total mass and energy but also on the properties of the mysterious dark energy driving its accelerated expansion.

If dark energy remains constant—as described by the cosmological constant—then the universe’s flatness will persist while expansion continues indefinitely. But if dark energy changes its strength over time, the geometry could shift. Some theories suggest that dark energy might weaken, allowing gravity to dominate again, leading to eventual collapse. Others propose it could strengthen, tearing apart galaxies, stars, and even atoms in a cataclysmic “Big Rip.”

The nature of dark energy remains one of modern physics’ greatest enigmas. Understanding it is essential not only for predicting the universe’s fate but also for deciphering its ultimate shape.

The Universe We See, and the Universe Beyond

When cosmologists say the universe is flat, they mean the observable universe—the part we can see, bounded by the speed of light and the age of the cosmos. But what lies beyond that horizon? The answer could redefine everything we think we know about geometry and reality.

If the universe is truly infinite, its shape may be meaningless in the conventional sense. Infinity has no edges, no boundaries, and no curvature we can measure. But if the universe is finite and wraps around itself, we might one day detect repeating patterns in the sky—echoes of light that have circled the cosmos more than once.

So far, searches for such patterns have come up empty. But some speculative models suggest that space may have a “multiply connected” topology, like a 3D torus or a dodecahedron. In these scenarios, traveling far enough in one direction could bring you back from another, creating a universe that is both finite and edgeless—a cosmic hall of mirrors.

The Quantum Foam and the Fabric of Reality

On the smallest scales imaginable, the smooth geometry of spacetime begins to break down. According to quantum theory, space is not continuous but fluctuates violently at scales near the Planck length—about 10⁻³⁵ meters. In this domain, known as quantum foam, spacetime may bubble, twist, and reconnect in a seething chaos beyond ordinary comprehension.

Some theories of quantum gravity—like loop quantum gravity and string theory—suggest that the universe’s large-scale shape may emerge from these microscopic structures. Space could be composed of discrete “atoms” of geometry, woven together by quantum interactions. In such a view, curvature is not fundamental but arises as an average property of a deeper, quantum fabric.

This union of the cosmic and the quantum remains one of physics’ greatest quests: to reconcile Einstein’s curved spacetime with the probabilistic nature of quantum mechanics. When we finally achieve this synthesis, we may discover that the true shape of the universe is neither flat nor curved in the classical sense, but something entirely new—woven from the geometry of information itself.

The Multiverse and Beyond

If inflationary theory is correct, our universe might be just one bubble in an infinite cosmic sea—a multiverse of universes, each with its own laws, constants, and geometry. Some may be open, others closed, others still with bizarre topologies beyond human imagination.

In this grander view, asking about “the” shape of the universe may be too narrow. Our observable cosmos could be merely one region of a much larger reality, shaped by conditions that vary from place to place. Some regions may expand faster, curve differently, or even have more (or fewer) spatial dimensions.

While the multiverse remains speculative, it offers a profound perspective: what we call the “universe” might be a local patch in an endless cosmic mosaic. The geometry we observe—flat, open, or closed—may be but one pattern in the infinite tapestry of creation.

The Human Perspective: Seeing Curvature in the Mind

When we speak of the shape of the universe, we are ultimately confronting the limits of perception. Our senses evolved to navigate the immediate world, not to comprehend spacetime curvature or multidimensional topology. Yet through mathematics, we have extended our reach across billions of light-years, tracing the universe’s structure through the faintest whispers of radiation.

The concept of curvature challenges our intuition. We are accustomed to thinking of space as emptiness, but in reality, it is a dynamic entity that shapes and is shaped by everything within it. The universe is not an arena where events happen—it is the event itself, evolving, bending, and expanding in concert with the matter it contains.

This understanding is both humbling and uplifting. It reminds us that our very existence is tied to the structure of spacetime—that the atoms in our bodies, the stars above, and the geometry of the cosmos are all woven from the same fundamental laws.

The Fate Written in Curvature

The universe’s shape does not merely describe its form; it determines its destiny. If the cosmos is open, it will expand forever, growing colder and darker until even atoms decay. If it is closed, it may one day contract into a fiery collapse, perhaps to begin anew. If it is flat, it will expand eternally, approaching an equilibrium where creation and decay balance in infinite stillness.

Current data favor the flat model, suggesting an endless expansion driven by dark energy. But the story is not over. As new telescopes—like the James Webb Space Telescope and the upcoming Euclid and Nancy Grace Roman missions—peer deeper into space and time, they may refine our measurements, perhaps even reveal subtle curvature we cannot yet detect.

Whatever the outcome, the universe’s geometry is not static—it evolves, just as our understanding does. Each discovery reshapes our view of reality, reminding us that knowledge itself is part of the universe’s unfolding story.

The Beauty of Curved Existence

Beyond equations and data, there is wonder. The question of the universe’s shape is not merely scientific—it is poetic. Whether the cosmos curves like a sphere, stretches like a saddle, or flows flat into infinity, it expresses a profound truth about existence: that we live within a vast and dynamic geometry of being.

When we gaze at the night sky, we are not looking outward but inward—seeing the curvature of space that connects us to everything else. The photons striking our eyes have traveled through the contours of spacetime, tracing the invisible architecture that holds galaxies, stars, and ourselves together.

To understand the universe’s shape is to glimpse the mind of nature itself—a mind that writes in the language of geometry, that sculpts infinity into form. Whether the universe is flat, round, or curvy, its true beauty lies not in its shape, but in its harmony—a balance so delicate that it allowed consciousness to arise and wonder at the cosmos that made it.

The Shape of Wonder

The question “Is the universe flat, round, or curvy?” does not end with measurement—it begins there. It is a doorway into deeper mysteries: Why does anything exist? Why does spacetime take the form it does? Could there be other shapes, other realities, beyond what our instruments can perceive?

In seeking the universe’s geometry, we are really tracing the outline of our own curiosity. We are creatures of curvature ourselves—bent by gravity, shaped by starlight, bound to a planet that moves through a spacetime we barely comprehend. Yet we dare to ask questions that reach to the edges of infinity.

Perhaps the true shape of the universe is not a line, a circle, or a saddle, but a question mark—a symbol of perpetual curiosity, curling back upon itself, inviting each generation to explore further. For as long as we look upward and wonder, the shape of space will remain not just a topic of science, but a testament to the human spirit.

And maybe, in the end, that is the most beautiful geometry of all—the curvature of thought that bends toward understanding, reaching endlessly into the infinite night.