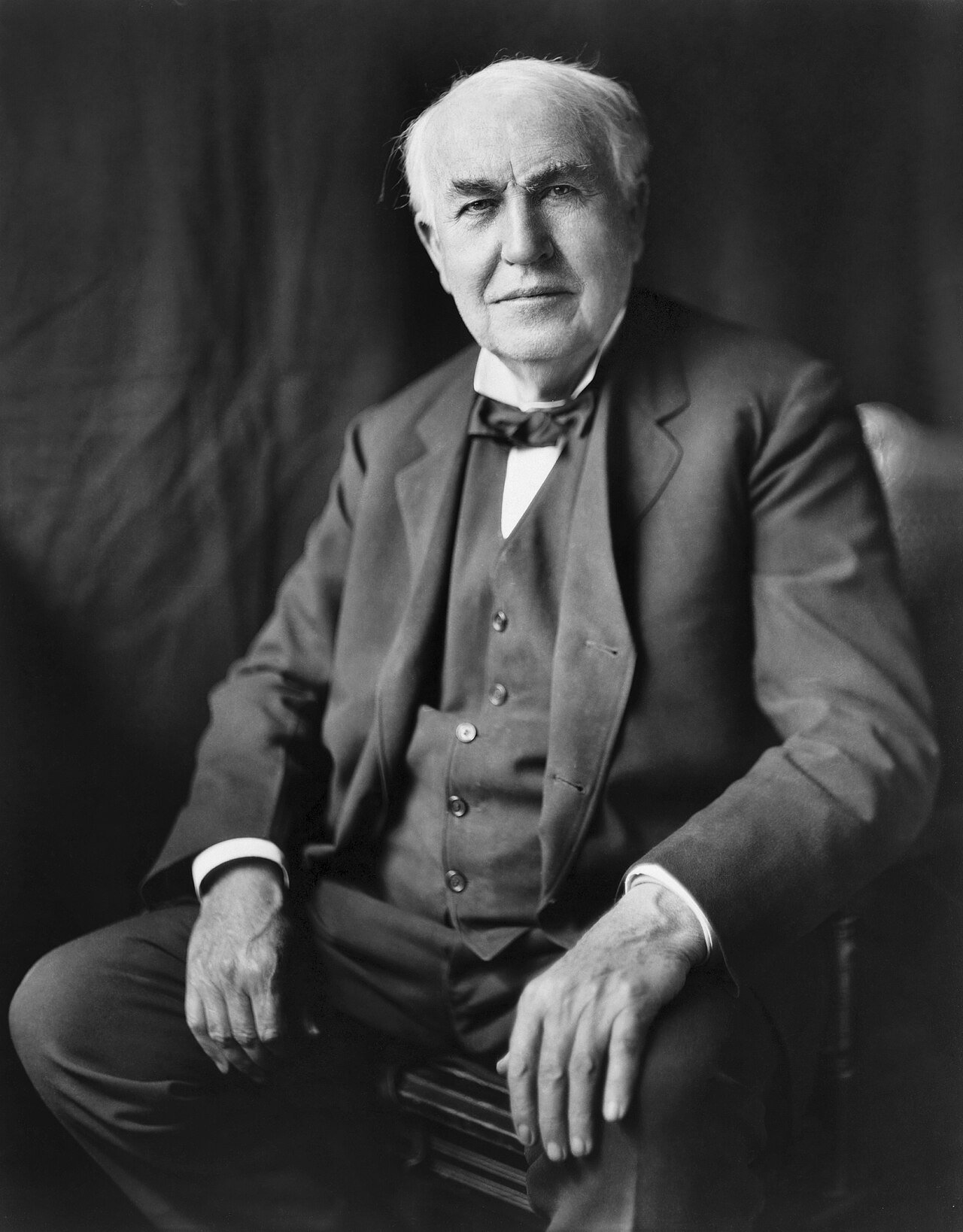

Thomas Edison (1847–1931) was an American inventor and entrepreneur who is widely regarded as one of history’s most prolific inventors. Born in Milan, Ohio, Edison developed numerous devices that greatly influenced life around the world, earning him the nickname “The Wizard of Menlo Park.” Among his most famous inventions are the phonograph, the motion picture camera, and the practical incandescent light bulb. Edison’s improvements to electric light and power distribution paved the way for widespread use of electricity in homes and businesses. He held over 1,000 patents, demonstrating his relentless pursuit of innovation. Beyond his technical achievements, Edison also pioneered the modern research laboratory, assembling teams of scientists and engineers to systematically develop new technologies. His work not only transformed industries but also shaped the modern era of invention and technological advancement.

Early Life and Education

Thomas Alva Edison was born on February 11, 1847, in Milan, Ohio, into a large family of modest means. His father, Samuel Edison Jr., was a Canadian-born political activist who was forced to flee to the United States after his involvement in the unsuccessful Mackenzie Rebellion in 1837. His mother, Nancy Elliott Edison, was a schoolteacher from New York, whose education played a crucial role in her son’s early development.

From a young age, Edison exhibited a deep curiosity and an independent spirit, traits that would later define his approach to invention. However, his formal education was brief and challenging. Enrolled in a local school, he struggled with the rigid structure and was labeled as “difficult” by his teachers. After just a few months, his mother withdrew him from the school and decided to educate him at home. Nancy Edison’s belief in her son’s potential was unwavering, and she provided him with a nurturing and intellectually stimulating environment that encouraged his natural curiosity.

Edison was particularly drawn to books on science and technology, devouring works such as Isaac Newton’s “Principia” and other scientific literature. His early education was characterized by hands-on experimentation, a method that suited his learning style far better than traditional schooling. By the age of 12, he had set up a small laboratory in the family’s basement, where he began conducting experiments with chemicals and basic electrical equipment.

Around this time, Edison also started working to support his family. He took up a job as a newsboy on the Grand Trunk Railroad, selling newspapers, candy, and other goods to passengers traveling between Port Huron, Michigan, and Detroit. The income from this work was vital to the Edison family, but the job also provided young Edison with new opportunities to experiment. He convinced the train conductor to let him set up a small printing press in a baggage car, where he published and sold a weekly newspaper called the “Grand Trunk Herald.” This venture was one of the first signs of Edison’s entrepreneurial spirit.

Edison’s time on the railroad also introduced him to the world of telegraphy. He became fascinated with the telegraph system used for communication along the train route and soon learned how to operate the equipment. His growing interest in electrical technology was evident, and it wasn’t long before he started tinkering with telegraph equipment, making improvements and modifications.

In 1862, a pivotal moment occurred when Edison saved a young boy from being struck by a runaway train. The boy’s grateful father, a stationmaster, taught Edison the basics of telegraphy as a reward. This event marked the beginning of Edison’s career as a telegraph operator, a job that would take him across the Midwest and expose him to various technological challenges and opportunities. It was during these early years that Edison began to develop his first inventions, setting the stage for what would become one of the most prolific careers in the history of invention.

First Inventions and Early Career

As a young telegraph operator, Thomas Edison traveled extensively across the Midwest, working in various cities and honing his skills in telegraphy. His job allowed him to interact with a diverse array of technologies and inventors, sparking his creativity and leading to his first significant inventions.

One of his early inventions was the automatic telegraph repeater, a device that could duplicate telegraph signals from one line to another, enabling the transfer of messages over long distances without the need for human intervention. This invention was a considerable improvement over existing telegraph systems, which required operators to manually relay messages at intermediate stations. Although Edison did not initially patent this device, it demonstrated his ability to identify and solve technical problems, laying the groundwork for future successes.

In 1868, at the age of 21, Edison moved to Boston, where he worked for the Western Union Company. Boston, with its vibrant intellectual and technological community, proved to be a fertile ground for Edison’s inventive mind. It was here that he developed and patented his first major invention, the electric vote recorder. This device was designed to speed up the process of tallying votes in legislative bodies by allowing representatives to cast their votes electronically. However, despite its technical innovation, the vote recorder was a commercial failure. Lawmakers were uninterested in the device, preferring the slower, more deliberative voting process that allowed for political maneuvering.

Undeterred by this setback, Edison continued to experiment and innovate. He realized that commercial success required not just technical ingenuity but also an understanding of market needs. This insight led him to focus on developing inventions that addressed practical problems with clear commercial potential.

In 1869, Edison moved to New York City, where he initially struggled to make ends meet. However, his fortunes changed when he was hired to repair a malfunctioning stock ticker at a brokerage firm. Edison not only fixed the machine but also proposed significant improvements to its design. His work impressed the firm’s manager, who offered him a job as an inventor.

Capitalizing on this opportunity, Edison developed the Universal Stock Ticker, a device that allowed stock prices to be transmitted over telegraph lines to brokerage firms across the country. The success of the Universal Stock Ticker led to the founding of Edison’s first company, the American Telegraph Works, in partnership with Franklin L. Pope and others. This venture marked the beginning of Edison’s entrepreneurial career and provided him with the financial resources to establish his first laboratory in Newark, New Jersey.

In Newark, Edison continued to refine his telegraph inventions. One of his most notable contributions during this period was the quadruplex telegraph, a system that allowed four telegraph signals to be transmitted simultaneously on a single wire. This invention significantly increased the efficiency of telegraph communication and was highly sought after by telegraph companies. Western Union, in particular, saw the potential of the quadruplex telegraph and acquired the rights to the invention for a substantial sum, further cementing Edison’s reputation as a leading inventor.

By the early 1870s, Thomas Edison had firmly established himself as a rising star in the world of invention. His early successes in telegraphy and his growing portfolio of patents provided the financial foundation for future ventures and allowed him to focus on more ambitious projects. Edison’s work during this period laid the groundwork for his later achievements, particularly in the fields of sound recording and electric lighting, which would revolutionize the world and secure his place in history.

The Phonograph: Revolutionizing Sound Recording

In 1877, Thomas Edison achieved one of his most famous and groundbreaking inventions—the phonograph. This invention not only revolutionized the way sound was recorded and reproduced but also marked the beginning of the modern music and entertainment industry.

The idea for the phonograph came to Edison while he was working on improvements to the telegraph and telephone. He noticed that telegraph messages could be recorded in the form of indentations on a piece of paper tape, and he wondered if a similar method could be used to record sound. Intrigued by the possibility, Edison began experimenting with various materials and designs, eventually developing a device that could record sound as indentations on a tinfoil-wrapped cylinder. This was the birth of the phonograph, the first machine capable of both recording and reproducing sound.

Edison’s first successful test of the phonograph occurred in December 1877. He recited the nursery rhyme “Mary Had a Little Lamb” into the machine, and to his amazement—and the amazement of those present—the device played back his voice. This achievement was nothing short of revolutionary, as it was the first time in history that human speech had been captured and replayed.

The phonograph was an instant sensation. Newspapers and magazines around the world hailed Edison as a genius, and the device was quickly dubbed the “talking machine.” Unlike many of Edison’s earlier inventions, which had been technical improvements on existing devices, the phonograph was a completely new concept with limitless potential applications. Edison himself recognized this, famously declaring that the phonograph would have many uses, including dictation, audiobooks for the blind, music playback, and family record-keeping.

Despite its initial success, the early phonograph was far from perfect. The tinfoil recordings were fragile and could only be played a few times before they became too worn to use. Additionally, the sound quality was poor by modern standards, and the machine itself was complex and expensive to produce. Nevertheless, the phonograph represented a major technological leap, and Edison continued to refine the device in the years that followed.

In 1878, Edison formed the Edison Speaking Phonograph Company to manufacture and market the phonograph. However, the commercial success of the phonograph was initially limited. The primary market for the device was as a novelty or curiosity, and the high cost and technical limitations made it impractical for widespread use. Edison soon shifted his focus to other projects, including the development of the electric light bulb, and the phonograph was temporarily sidelined.

It wasn’t until the 1880s, when Edison returned to the phonograph, that the device began to reach its full potential. By this time, Edison had developed new methods for recording sound onto wax cylinders, which were more durable and produced better sound quality than the original tinfoil. The introduction of these wax cylinders marked a significant improvement in the phonograph’s performance, making it more viable for commercial and consumer use.

The phonograph’s impact on society was profound. It paved the way for the modern music industry, enabling the mass production and distribution of music recordings. It also led to the development of new forms of entertainment, such as recorded performances and radio broadcasts, which would dominate the 20th century. Additionally, the phonograph had significant cultural implications, as it allowed people to experience music and voices from around the world, breaking down geographical and cultural barriers.

Edison’s work on the phonograph exemplified his approach to invention: a combination of technical innovation, persistence, and an eye for commercial potential. The phonograph remains one of Edison’s most iconic inventions, and it solidified his reputation as the “Wizard of Menlo Park,” a nickname he earned for the groundbreaking work conducted at his research laboratory in Menlo Park, New Jersey

The Electric Light Bulb: Lighting the World

Thomas Edison’s most famous invention is undoubtedly the practical electric light bulb, a creation that not only transformed the way people lived and worked but also established the foundation for the modern electric utility industry.

Before Edison’s work, electric lighting was not a new concept. Several inventors, including Sir Humphry Davy and Joseph Swan, had developed early forms of electric lamps, but these devices were either too dim, too expensive, or too short-lived to be practical for widespread use. Edison’s goal was to create a long-lasting, affordable, and reliable light bulb that could be used in homes, businesses, and public spaces.

Edison began his work on the electric light bulb in 1878, assembling a team of skilled scientists, engineers, and technicians at his Menlo Park laboratory. His approach was systematic: rather than focusing solely on the bulb itself, Edison recognized that an effective lighting system would require innovations in materials, manufacturing processes, and electrical distribution.

The key challenge Edison faced was finding a suitable filament material for the bulb. The filament needed to be durable enough to withstand prolonged heating without burning out, yet inexpensive to produce. Edison and his team tested thousands of materials, including platinum, carbonized paper, and bamboo, in their search for the ideal filament. After exhaustive experimentation, they discovered that carbonized bamboo provided the right balance of durability and cost-effectiveness.

In October 1879, Edison and his team successfully demonstrated a working light bulb that could burn for over 13 hours. This breakthrough marked a significant milestone in the development of electric lighting, but Edison knew that creating a practical lighting system required more than just a reliable bulb. He also developed a complete electrical distribution system, including generators, wiring, and switches, to deliver electricity to homes and businesses.

To bring his vision to life, Edison founded the Edison Electric Light Company in 1878 and began working on the construction of the world’s first central power station. In September 1882, the Pearl Street Station in lower Manhattan began supplying electricity to a small area of New York City. This marked the beginning of the electric age, as the station powered hundreds of incandescent bulbs in homes, offices, and public spaces.

Edison’s electric lighting system was an immediate success, and demand for electric light rapidly spread across the United States and beyond. However, Edison’s work was not without its challenges. He faced intense competition from other inventors and entrepreneurs, most notably Nikola Tesla and George Westinghouse, who were developing an alternative method of electrical distribution known as alternating current (AC). Edison’s system used direct current (DC), which had limitations in terms of long-distance power transmission.

The rivalry between Edison’s DC system and the AC system, championed by Tesla and Westinghouse, became known as the “War of Currents.” Edison argued that DC was safer and more reliable, while proponents of AC pointed to its ability to efficiently transmit electricity over long distances. Despite Edison’s efforts to promote DC, including a public campaign highlighting the dangers of AC, the advantages of AC eventually led to its widespread adoption.

Although Edison’s DC system ultimately lost out to AC, his contributions to the development of electric lighting and power distribution were monumental. The incandescent light bulb became a symbol of technological progress and innovation, and Edison’s work laid the groundwork for the modern electric utility industry. His inventions not only changed the way people lived, making it possible to work and socialize after dark, but also contributed to the growth of cities, industries, and the global economy.

Edison’s electric light bulb remains one of the most enduring symbols of his genius and perseverance. It was an invention that illuminated not only homes and streets but also the path toward a future shaped by technology and innovation.

Expanding into Electric Power Systems

Following the success of the electric light bulb, Thomas Edison turned his attention to the broader challenge of developing a complete electric power system that could deliver electricity efficiently and reliably to homes and businesses. This endeavor would not only revolutionize the way people lived and worked but also establish the foundation for the modern electric utility industry.

Edison’s vision for an electric power system began with the construction of the Pearl Street Station in New York City, which became operational on September 4, 1882. The station was the first commercial central power plant in the United States, and it represented a significant leap forward in the generation and distribution of electricity. Located in the heart of Manhattan, the Pearl Street Station used steam engines to drive electric generators, which produced direct current (DC) electricity.

The power generated by the Pearl Street Station was distributed to a small area of lower Manhattan, providing electricity to 59 customers who powered 3,000 incandescent lamps. The success of the station demonstrated the feasibility of Edison’s electric lighting system and marked the beginning of the electric utility industry. For the first time, electricity was available on demand, transforming night into day and enabling a host of new technologies and industries.

However, the expansion of Edison’s electric power system was not without challenges. The use of direct current presented significant limitations, particularly in terms of transmitting electricity over long distances. DC power could only be efficiently transmitted over short distances, which meant that power stations needed to be located close to their customers. This limitation made it difficult to scale the system to serve larger areas, such as entire cities or regions.

As Edison’s electric power system expanded, a new challenge emerged in the form of competition from alternating current (AC) systems. AC power, championed by inventors like Nikola Tesla and entrepreneurs like George Westinghouse, offered significant advantages over DC power. AC systems could easily change the voltage of electricity using transformers, allowing it to be transmitted over long distances with minimal energy loss. This capability made AC power more practical for large-scale distribution and led to a fierce rivalry between the proponents of AC and DC systems.

The “War of Currents” was characterized by intense competition, public debates, and even smear campaigns. Edison, who had invested heavily in DC technology, argued that AC power was dangerous and posed a risk to public safety. He went so far as to demonstrate the dangers of AC by publicly electrocuting animals, a move that shocked many but failed to sway public opinion in favor of DC.

Despite Edison’s efforts, the technical advantages of AC power became increasingly clear. AC systems could power entire cities from a single, centralized power plant, making them more cost-effective and efficient than DC systems. By the late 1880s, AC power was gaining widespread adoption, and Edison’s DC system was gradually phased out in favor of AC.

While Edison ultimately lost the War of Currents, his contributions to the development of electric power systems were far from overshadowed. The principles and technologies he developed laid the groundwork for the modern electrical infrastructure, even as alternating current (AC) became the dominant method of electrical distribution.

One of Edison’s most significant contributions to the electric power industry was his invention of the electric meter, which allowed for the accurate measurement of electricity consumption. This innovation was crucial for the commercial viability of electric power, as it enabled utility companies to charge customers based on their actual electricity usage, rather than a flat rate. Edison’s meters were among the first of their kind and became a standard component of electric power systems worldwide.

Edison also played a critical role in establishing the business model for electric utilities. He envisioned a network of central power stations, each serving a specific geographical area, with customers paying for the electricity they consumed. This model, which he implemented with the Pearl Street Station, became the blueprint for the electric utility industry and remains in use today. The idea of centralized power generation and distribution was revolutionary, and it transformed electricity from a luxury available only to the wealthy into a utility accessible to the general public.

Despite the eventual dominance of AC power, Edison’s DC systems continued to operate in some areas for many years. In fact, parts of New York City’s financial district were powered by DC electricity until as late as 2007, a testament to the durability and reliability of Edison’s original system. Moreover, Edison’s work on electrical systems extended beyond lighting and power distribution. He developed numerous other electrical devices and technologies, including the first commercially viable electric motor, which further expanded the applications of electricity in industry and everyday life.

Edison’s foray into electric power systems also had a profound impact on the urban environment. The availability of reliable electric lighting and power transformed cities, enabling the development of skyscrapers, subways, and a host of other innovations that defined the modern urban landscape. The ability to light streets and buildings after dark also had significant social and cultural implications, extending the hours during which people could work, shop, and socialize, and contributing to the vibrant nightlife that became a hallmark of modern cities.

While Edison may not have been the ultimate victor in the War of Currents, his work in the field of electric power was transformative. His inventions and business strategies laid the foundation for the modern electric utility industry, and his vision of a world powered by electricity became a reality. Edison’s legacy in this area is not just one of technological innovation, but also of creating the systems and infrastructure that allowed those innovations to be widely adopted and integrated into everyday life.

The experience of competing with AC power systems also highlighted one of Edison’s most remarkable qualities: his ability to adapt and evolve. Although he had invested heavily in DC technology, Edison did not allow the eventual success of AC to diminish his contributions. Instead, he continued to innovate in other areas, applying the lessons he had learned from the development of electric power systems to new challenges and opportunities.

Edison’s work on electric power systems represents one of the most significant chapters in his career. It was a period of intense creativity, competition, and learning, during which Edison not only developed groundbreaking technologies but also helped to shape the future of electricity and its role in society. His contributions to this field remain an essential part of his legacy as one of the greatest inventors of all time.

Motion Pictures: Pioneering the Film Industry

In addition to his groundbreaking work in electricity and sound recording, Thomas Edison played a pivotal role in the birth of the motion picture industry. His contributions to this field helped lay the foundation for cinema as we know it today, transforming entertainment and creating a new medium for storytelling, art, and communication.

Edison’s interest in motion pictures was sparked by his earlier work on the phonograph. Having successfully captured and reproduced sound, he became intrigued by the idea of doing the same for moving images. In the late 1880s, Edison tasked his assistant, William Kennedy Laurie Dickson, with developing a device that could record and display motion pictures. This effort led to the invention of the kinetoscope, a pioneering motion picture viewing device.

The kinetoscope was a relatively simple machine that used a continuous loop of film, threaded through a series of rollers and lit by an incandescent light bulb, to project moving images onto a screen. The images were viewed through a peephole, one person at a time, making the kinetoscope a precursor to later movie projectors. In 1891, Edison and his team successfully demonstrated the kinetoscope, and by 1893, it was ready for commercial production.

Edison’s kinetoscope parlors, which opened in cities across the United States, became popular attractions where people could pay to watch short films. These early films, produced by Edison’s studio, the Black Maria, were typically only a few minutes long and depicted simple scenes, such as a man sneezing or a couple dancing. Despite their brevity, these films were a marvel of technology and captivated audiences with their novelty.

However, the kinetoscope had its limitations. Because it could only be viewed by one person at a time, it was not well-suited for large audiences. Recognizing this, Edison and his team began working on a projection system that could display motion pictures to a larger audience. This work led to the development of the Vitascope, an early film projector that Edison introduced in 1896. The Vitascope was among the first devices to project films onto a screen, paving the way for the modern movie theater experience.

Edison’s contributions to motion pictures extended beyond the development of viewing devices. He also played a significant role in the production and distribution of films. Edison’s studio, the Black Maria, was the first movie studio in the United States, and it produced hundreds of short films during its operation. These films ranged from simple recordings of everyday activities to early narrative films that told a story. Edison’s involvement in film production helped establish the conventions of early cinema and set the stage for the growth of the film industry.

One of the most notable aspects of Edison’s work in motion pictures was his commitment to innovation. He and his team were constantly experimenting with new techniques and technologies, such as synchronized sound and color film. Although many of these innovations would not be fully realized until after Edison’s time, his early experiments laid the groundwork for future developments in the film industry.

Edison’s influence on the motion picture industry was not without controversy. He was known for aggressively protecting his patents, and he often engaged in legal battles with other inventors and filmmakers. Edison’s Motion Picture Patents Company, also known as the “Edison Trust,” sought to control the production, distribution, and exhibition of films in the United States. This monopolistic approach led to widespread resistance from independent filmmakers, who eventually relocated to Hollywood, California, to escape Edison’s influence.

Despite these controversies, Edison’s impact on the motion picture industry is undeniable. His inventions and innovations helped transform motion pictures from a technological curiosity into a major form of entertainment and communication. The techniques and technologies he developed continue to influence filmmaking today, and his contributions to the industry remain a significant part of his legacy.

Edison’s work in motion pictures exemplifies his ability to envision the future and create the tools needed to realize that vision. His pioneering efforts in this field helped shape the course of entertainment history, and his influence can still be felt in the movies and media we enjoy today.

Later Years and Legacy

As Thomas Edison entered the later years of his life, his role as an inventor and businessman evolved, but his influence on technology and industry remained profound. By the time of his death in 1931, Edison had amassed 1,093 U.S. patents and countless more in other countries, making him one of the most prolific inventors in history. His inventions and innovations spanned a wide range of fields, from electricity and sound recording to motion pictures and communication technologies.

In the early 20th century, Edison continued to innovate, although his pace of invention slowed somewhat compared to his earlier years. He focused on refining existing technologies and exploring new areas of interest, such as the development of synthetic materials and the improvement of storage batteries. One of Edison’s notable achievements during this period was the development of the Edison storage battery, a nickel-iron battery that was more durable and longer-lasting than earlier designs. This invention had applications in a variety of industries, including transportation and renewable energy.

Edison’s later years were also marked by his continued involvement in the business world. He remained active in the companies he had founded, including General Electric and the Edison Electric Light Company, and he played a key role in shaping the direction of these businesses. Edison’s entrepreneurial spirit and business acumen were essential to his success as an inventor, and they helped ensure that his inventions were not only technologically groundbreaking but also commercially viable.

Throughout his life, Edison was driven by a relentless curiosity and a desire to solve problems. This drive led him to explore a wide range of fields and to make significant contributions to many different industries. Edison’s approach to invention was characterized by persistence, experimentation, and a willingness to take risks. He famously remarked that “genius is one percent inspiration and ninety-nine percent perspiration,” a statement that reflects his belief in the importance of hard work and determination.

Edison’s legacy is not only defined by his inventions but also by the impact he had on the world. His work helped usher in the modern era, transforming the way people lived, worked, and communicated. The technologies he developed laid the foundation for many of the conveniences and advancements we take for granted today, from electric lighting and recorded music to motion pictures and telecommunications.

In recognition of his contributions, Edison received numerous honors and accolades during his lifetime. He was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal in 1928, one of the highest honors the United States can bestow on a civilian, in recognition of his achievements in electricity and sound recording. Edison was also honored by various scientific and academic institutions, and he was inducted into several prestigious organizations, including the National Academy of Sciences and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. These accolades were a testament to the profound impact of his work on science, industry, and society as a whole.

Despite his many successes, Edison’s later years were not without challenges. He faced health issues, including hearing loss, which had plagued him for much of his life and became more pronounced as he aged. Nevertheless, he remained active and engaged in his work, continuing to invent and experiment even in his final years. Edison’s passion for discovery never waned, and he spent his last days working in his laboratory, surrounded by the tools and materials that had been a constant part of his life.

Edison’s personal life also saw significant developments during his later years. His first wife, Mary Stilwell Edison, passed away in 1884, leaving him a widower with three young children. In 1886, Edison remarried Mina Miller, the daughter of a prominent inventor and industrialist. Mina became a key figure in Edison’s life, managing his affairs and providing him with emotional support. The couple had three children together, and Mina played an important role in preserving Edison’s legacy after his death.

Edison’s contributions to society extended beyond his inventions. He was a strong advocate for education and believed in the importance of scientific literacy. He supported various educational initiatives and institutions, and he often spoke about the need for practical, hands-on learning experiences for students. Edison’s belief in the value of education was reflected in his own life; despite having little formal schooling, he was a lifelong learner who constantly sought to expand his knowledge and skills.

As Edison’s life drew to a close, his legacy was already being recognized and celebrated. In 1929, a special event was held in his honor at Henry Ford’s Greenfield Village in Michigan, where Edison reenacted the invention of the incandescent light bulb. The event was attended by President Herbert Hoover and other dignitaries, and it served as a testament to Edison’s enduring impact on the world.

On October 18, 1931, Thomas Alva Edison passed away at his home in West Orange, New Jersey, at the age of 84. His death was met with an outpouring of grief and admiration from people around the world. In a symbolic gesture, communities across the United States turned off their lights for one minute to honor the man who had brought electric light to the masses.

Edison’s legacy continues to be felt today, more than a century after his most famous inventions were introduced. The technologies he developed have evolved and improved, but their fundamental principles remain the same. Electric lighting, sound recording, motion pictures, and countless other innovations can all trace their origins back to Edison’s work.

Moreover, Edison’s approach to invention—characterized by perseverance, experimentation, and a willingness to embrace failure—has inspired generations of inventors and entrepreneurs. His belief in the power of innovation to change the world remains a guiding principle for those who seek to solve the challenges of today and tomorrow.

Edison’s contributions to the modern world are immeasurable, and his influence extends far beyond the specific inventions he created. He helped shape the course of technological development in the 20th century and laid the groundwork for the digital age. Edison’s legacy is not just one of machines and devices; it is a legacy of imagination, creativity, and the relentless pursuit of progress.

As we reflect on Edison’s life and work, it is clear that he was more than just an inventor—he was a visionary who saw the potential for technology to transform society and improve the human condition. His inventions brought light to the darkness, sound to silence, and motion to stillness. In doing so, Edison changed the world, and his legacy will continue to inspire and influence future generations for years to come.

Edison’s Influence on Modern Innovation

The influence of Thomas Edison on modern innovation extends far beyond his lifetime, impacting both the trajectory of technological advancement and the ethos of the entrepreneurial spirit. As one of the most prolific inventors in history, Edison not only introduced groundbreaking inventions but also pioneered methods of research and development that have become standard practices in the innovation ecosystem today.

One of the most enduring aspects of Edison’s legacy is his establishment of the first industrial research laboratory. Located in Menlo Park, New Jersey, this lab was a novel concept in the late 19th century, combining the talents of engineers, chemists, and other specialists to work collaboratively on inventing new technologies. This interdisciplinary approach to problem-solving was revolutionary and laid the groundwork for the modern R&D labs that are now integral to corporations, universities, and government agencies around the world.

Edison’s emphasis on practical, market-driven innovation is another key element of his influence. Unlike many inventors who focused solely on the scientific aspects of their work, Edison was keenly aware of the commercial potential of his inventions. He understood that for a new technology to succeed, it had to be not only functional but also accessible and desirable to the public. This focus on the consumer experience is a hallmark of modern product development and is evident in everything from the user-friendly design of smartphones to the seamless integration of digital services in everyday life.

Edison also pioneered the concept of vertical integration in business. He recognized that to bring his inventions to market, he needed to control every aspect of their production and distribution. This led him to establish companies that not only manufactured his products but also supplied the raw materials and managed the sales and distribution channels. This approach allowed Edison to ensure the quality and availability of his inventions and maximized their impact on the market. Today, vertical integration is a common strategy used by companies in various industries to streamline operations and increase efficiency.

Another significant contribution Edison made to modern innovation was his approach to intellectual property. Edison was acutely aware of the importance of protecting his inventions through patents, and he was involved in numerous legal battles to defend his rights. His aggressive stance on intellectual property set a precedent for how inventors and companies manage and protect their innovations today. The patent system, which allows inventors to safeguard their creations and benefit financially from them, has been instrumental in fostering innovation and encouraging investment in new technologies.

Edison’s approach to failure also offers valuable lessons for modern innovators. He famously conducted thousands of experiments before successfully inventing the incandescent light bulb, demonstrating an extraordinary level of persistence and resilience. Edison viewed failure not as a setback but as a learning opportunity, each unsuccessful attempt bringing him one step closer to success. This mindset is now widely recognized as crucial in the innovation process, where trial and error are often necessary to achieve breakthrough results.

The impact of Edison’s work on modern innovation is also reflected in the industries he helped create. The electric power industry, the motion picture industry, and the sound recording industry all owe their existence, in large part, to Edison’s inventions and business acumen. These industries have grown and evolved over the years, but their foundations were laid by Edison’s early efforts. His work in these fields has had a lasting influence, shaping the way we generate, distribute, and consume electricity, entertainment, and information.

Moreover, Edison’s legacy lives on in the culture of innovation that he helped to establish. The idea that technology can solve problems and improve lives is a fundamental belief that drives much of the innovation happening today. Whether it’s developing new medical treatments, creating sustainable energy solutions, or advancing digital technologies, the spirit of invention that Edison embodied continues to inspire and motivate people around the world.