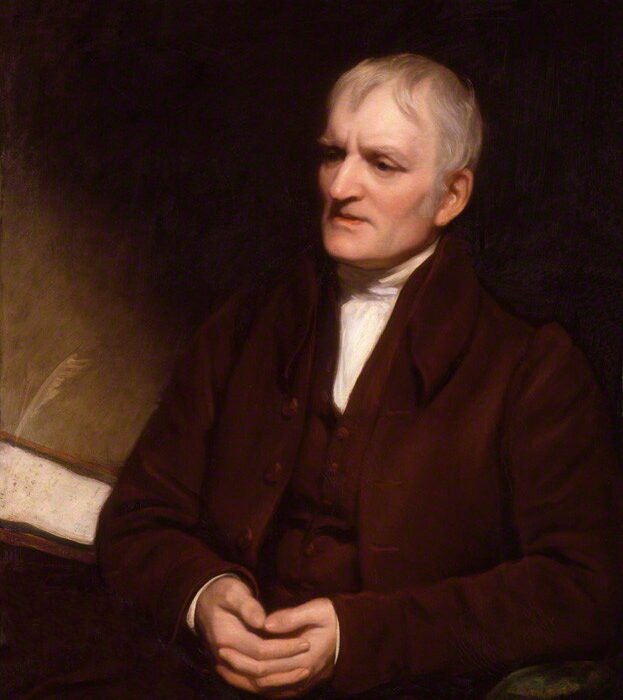

Thomas Robert Malthus (1766-1834) was an English economist and demographer best known for his influential theories on population growth. In his seminal work, An Essay on the Principle of Population (1798), Malthus argued that while population grows exponentially, food production only increases arithmetically, leading to inevitable shortages. He theorized that without checks such as famine, disease, and war, population growth would outstrip resources, resulting in societal collapse. Malthus’s ideas sparked significant debate and influenced economic and social policies, particularly in the areas of population control and welfare. Though later criticized and refined, his work laid the groundwork for the study of demography and had a lasting impact on economics, particularly in discussions of resource scarcity and environmental sustainability. Malthus’s ideas remain relevant today, informing debates on population dynamics, resource management, and the challenges of sustainable development.

Early Life and Education

Thomas Robert Malthus was born on February 13, 1766, in Westcott, Surrey, England, into a prosperous family. He was the seventh child of Daniel Malthus and Henrietta Catherine. The Malthus family was well-connected and intellectual, offering young Thomas an environment rich in philosophical discourse. His father, Daniel Malthus, was a friend of prominent philosophers like David Hume and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, which exposed Thomas to intellectual debates from an early age.

Malthus was educated privately, initially at home by his father and then at a school in Dorking. He was later enrolled at Warrington Academy, a dissenting academy that emphasized critical thinking and nonconformist religious principles. However, the pivotal moment in his education came when he attended Jesus College, Cambridge, in 1784. At Cambridge, Malthus excelled in his studies, particularly in mathematics, and graduated with honors in 1788. He also took holy orders, being ordained as an Anglican clergyman in 1789.

His time at Cambridge laid the foundation for his intellectual development. Malthus was influenced by the ideas of the Enlightenment, particularly those related to reason, science, and progress. However, he also became increasingly skeptical of the more utopian aspects of Enlightenment thought, particularly the idea that society could achieve perfect equality and harmony. This skepticism would later be a significant influence on his work, especially his most famous theory concerning population growth.

After Cambridge, Malthus took up a position as a curate in a small parish in Surrey. It was during this time that he began to reflect on the issues of population growth and human misery, which were exacerbated by the agricultural and industrial revolutions in Britain. His observations and reflections eventually culminated in his most famous work, “An Essay on the Principle of Population,” published in 1798.

Malthus’s early life and education thus set the stage for his later work. The intellectual environment of his childhood, combined with the rigorous academic training at Cambridge, equipped him with the tools to critically engage with the social and economic issues of his time. His skepticism of utopian ideals, shaped by his observations as a clergyman, would become central to his later arguments about the limits of human progress.

Malthus’s Early Career and Influences

After completing his education, Malthus entered a period of intellectual development shaped by his interactions with the major thinkers of his time and his experiences as a clergyman. The late 18th century was a period of significant social and economic change in Britain, with the Industrial Revolution transforming the economy and society. Malthus was deeply concerned with the consequences of these changes, particularly the impact on the poor and the potential for widespread social unrest.

Malthus was influenced by a range of contemporary thinkers, including his father’s friends, who were part of the intellectual circle known as the Enlightenment. However, it was the work of economists like Adam Smith, David Ricardo, and others that had a profound impact on his thinking. Smith’s ideas on free markets and the division of labor provided Malthus with a framework for understanding economic growth and its effects on society. At the same time, the writings of philosophers like William Godwin and the Marquis de Condorcet, who argued for the perfectibility of human society, challenged Malthus to think critically about the limits of human progress.

It was in response to these utopian ideas that Malthus began to formulate his own theory of population. He was particularly troubled by the notion that human society could achieve a state of perfect equality and harmony, believing that such ideas were not only unrealistic but also dangerous. Malthus’s observations of the conditions of the poor in Britain, combined with his study of history, led him to conclude that population growth would always outpace the growth of resources, leading to inevitable shortages and suffering.

In 1798, Malthus published the first edition of “An Essay on the Principle of Population.” The essay was initially published anonymously, but it quickly became one of the most controversial and influential works of its time. In the essay, Malthus argued that population growth would always tend to outstrip the growth of food supply, leading to what he called “positive checks” on population, such as famine, disease, and war. He also identified “preventive checks,” such as moral restraint and delayed marriage, as ways to control population growth. However, Malthus was pessimistic about the ability of these preventive checks to significantly alter the course of population growth.

Malthus’s early career was thus marked by his engagement with the major social and economic issues of his time. His work was a direct response to the optimistic visions of human progress put forward by Enlightenment thinkers, and it laid the groundwork for his later contributions to economics and social theory.

The Publication of the Essay on Population

The publication of “An Essay on the Principle of Population” in 1798 marked a turning point in Malthus’s life and career. The essay was a bold and controversial work that challenged the prevailing optimism of the Enlightenment. In it, Malthus argued that population growth would always tend to outstrip the growth of food supply, leading to inevitable shortages and suffering. His ideas were a direct response to the utopian visions of thinkers like William Godwin and the Marquis de Condorcet, who believed that human society could achieve a state of perfect equality and harmony.

Malthus’s essay was grounded in empirical observations and historical analysis. He argued that throughout history, population growth had always been checked by famine, disease, and war, which he called “positive checks.” These checks, he argued, were the natural consequences of population growth outstripping the growth of resources. Malthus also identified “preventive checks,” such as moral restraint and delayed marriage, as ways to control population growth. However, he was pessimistic about the ability of these preventive checks to significantly alter the course of population growth.

The essay was initially published anonymously, but it quickly attracted widespread attention. Malthus’s ideas were both praised and criticized, and the essay became one of the most influential works of its time. Some saw Malthus as a prophet of doom, while others saw him as a realist who was simply pointing out the harsh realities of human existence. The essay also had a significant impact on public policy, particularly in the areas of population control and poverty relief.

In subsequent editions of the essay, Malthus expanded on his ideas and addressed some of the criticisms that had been leveled against him. He also refined his arguments, distinguishing between different types of population checks and exploring the implications of his theory for economic and social policy. Despite the controversy surrounding his work, Malthus’s ideas became central to the emerging field of political economy, and he is often regarded as one of the founders of modern economics.

The publication of the essay also marked a turning point in Malthus’s personal life. He became a prominent public figure and was appointed to several academic positions, including a professorship of history and political economy at the East India Company College in Hertfordshire. This position allowed Malthus to continue his research and writing while also teaching and influencing a new generation of students.

The publication of “An Essay on the Principle of Population” was thus a defining moment in Malthus’s career. The essay challenged the prevailing optimism of the Enlightenment and laid the groundwork for his later contributions to economics and social theory. Despite the controversy it generated, the essay remains one of the most important works in the history of economic thought.

Malthusian Theory and its Critiques

Malthus’s theory of population, as presented in “An Essay on the Principle of Population,” has had a profound and lasting impact on economic and social thought. The central idea of Malthusian theory is that population growth tends to outstrip the growth of resources, leading to inevitable shortages and suffering. Malthus argued that population grows geometrically, while food supply grows arithmetically, creating a situation where the population would inevitably exceed the ability of resources to sustain it.

Malthus’s theory was both influential and controversial. On the one hand, it provided a stark and sobering counterpoint to the optimism of the Enlightenment, challenging the idea that human society could achieve perfect equality and harmony. On the other hand, it was criticized for being overly pessimistic and for failing to account for the potential of human innovation and technological progress to increase the supply of resources.

One of the most significant criticisms of Malthus’s theory came from the economist David Ricardo, who argued that Malthus had underestimated the ability of technological progress and capital accumulation to increase agricultural productivity. Ricardo believed that Malthus’s pessimism was unwarranted and that economic growth could continue indefinitely as long as technological innovation kept pace with population growth. This debate between Malthus and Ricardo laid the groundwork for much of the subsequent development of economic theory.

Malthus’s theory was also criticized by Karl Marx, who saw it as a justification for the exploitation of the working class. Marx argued that Malthus’s theory was based on a flawed understanding of the nature of capitalist production, which he believed was the real cause of poverty and suffering. Marx rejected the idea that population growth was the primary cause of social and economic problems, arguing instead that these issues were rooted in the dynamics of capitalist production. According to Marx, the Malthusian theory wrongly attributed poverty and scarcity to natural laws rather than recognizing them as products of social and economic systems. For Marx, the real problem lay in the unequal distribution of resources, which was driven by the capitalist mode of production.

Marx believed that under capitalism, the ownership and control of the means of production were concentrated in the hands of a few, leading to the exploitation of the working class. This exploitation created a situation where the working class produced more value than they received in wages, generating surplus value for the capitalists. Marx argued that the resulting economic inequalities and cycles of boom and bust were inherent to capitalism, not the consequence of population growth outstripping resources, as Malthus had proposed.

Furthermore, Marx viewed Malthus’s theory as ideologically convenient for the ruling classes, as it provided a justification for social inequality and the harsh treatment of the poor. By framing poverty as a natural outcome of population pressure, Malthus’s theory absolved the ruling classes of responsibility for the social conditions of the time. Instead of addressing the structural issues of capitalism, the Malthusian perspective suggested that poverty was inevitable, thus discouraging social reform and reinforcing existing power structures.

In contrast, Marx argued that social change could only come through the overthrow of the capitalist system and the establishment of a classless society. He believed that in a socialist society, where the means of production were owned collectively, the problems associated with population growth could be managed more effectively. Resources could be distributed according to need, rather than profit, and technological advancements could be used to improve living standards for all, rather than to increase the wealth of a few.

Despite these criticisms, Malthus’s ideas continued to have a significant influence on economic and social thought. In the 19th century, his theory was used to justify policies that restricted aid to the poor, under the assumption that such aid would only encourage population growth and exacerbate poverty. The Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834, for example, was influenced by Malthusian thinking and aimed to make poor relief less attractive, thereby discouraging the poor from having large families.

Malthus’s theory also found resonance in the field of biology, where it influenced Charles Darwin’s development of the theory of natural selection. Darwin recognized the parallels between Malthus’s ideas on population growth and the struggle for existence in the natural world, where only the fittest survive. This connection between Malthusian theory and evolutionary biology further cemented Malthus’s place in the history of ideas.

However, the 20th century saw new challenges to Malthusian theory, particularly as technological advancements in agriculture and industry led to unprecedented increases in food production and living standards. The Green Revolution, for example, demonstrated that human ingenuity could overcome the limitations that Malthus had described, at least in the short term. These developments called into question the inevitability of the Malthusian trap, where population growth would inevitably lead to scarcity and suffering.

Nonetheless, Malthus’s ideas have experienced a resurgence in recent years, particularly in discussions about environmental sustainability and resource depletion. The concept of carrying capacity, which is central to modern ecological thought, is rooted in Malthusian principles. As concerns about climate change, food security, and overpopulation grow, the Malthusian perspective remains relevant, highlighting the ongoing tension between population growth and the planet’s finite resources.

Malthus’s Later Works and Economic Theories

Following the publication of his seminal essay, Malthus continued to refine and expand his ideas, contributing significantly to the fields of economics and social theory. While his population theory remained central to his work, Malthus also engaged with a wide range of economic issues, including the nature of wealth, the distribution of resources, and the functioning of markets. His later writings reflect his deepening engagement with the economic debates of his time and his evolving views on the relationship between population, resources, and economic growth.

One of Malthus’s most important later works was “An Inquiry into the Nature and Progress of Rent” (1815), in which he developed the concept of economic rent. Malthus argued that rent was a payment made to landowners for the use of land, which arose because of the differences in the fertility and location of land. The most fertile and well-located land would generate higher rents, as it could produce more output with the same amount of labor and capital. This concept of rent became a cornerstone of classical economics and influenced subsequent economists, including David Ricardo, who built upon Malthus’s ideas in his theory of comparative advantage.

In 1820, Malthus published “Principles of Political Economy,” where he addressed some of the weaknesses he saw in the work of his contemporaries, particularly Ricardo. Malthus disagreed with Ricardo’s theory of value, which was based on the labor theory of value, and instead argued for a more demand-driven approach. He believed that effective demand, or the ability and willingness of consumers to purchase goods and services, was crucial for economic stability. Malthus warned that an imbalance between production and consumption could lead to economic stagnation, a view that anticipated later Keynesian economics. His concern was that if savings outpaced investment, it could result in insufficient demand, leading to economic downturns.

Malthus also contributed to debates on the Corn Laws, which were tariffs on imported grain designed to protect British agriculture. He supported the Corn Laws, arguing that they helped maintain agricultural production and prevent dependence on foreign imports. Malthus believed that a strong agricultural sector was essential for national security and economic stability. However, his support for the Corn Laws put him at odds with many of his contemporaries, including Ricardo, who argued that free trade would benefit the economy by lowering food prices and allowing capital to flow into more productive sectors.

Throughout his later career, Malthus remained concerned with the social implications of economic policy. He was a vocal advocate for the poor, arguing that social and economic policies should aim to alleviate poverty and improve living standards. However, his views on how to achieve these goals were shaped by his belief in the limits imposed by population growth. Malthus supported education and moral reform as means of encouraging population control, and he believed that charity should be carefully managed to avoid creating dependency.

Malthus’s later works also reflect his ongoing engagement with the scientific developments of his time. He corresponded with leading scientists and thinkers, including Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace, who were influenced by his ideas on population pressure. Malthus’s emphasis on the struggle for resources and the role of competition in shaping human society resonated with the emerging theory of evolution, providing a social and economic context for Darwin’s ideas on natural selection.

Despite his contributions to economic theory, Malthus’s later works did not achieve the same level of recognition as his essay on population. His ideas on rent, demand, and economic policy were often overshadowed by the more dominant theories of Ricardo and other classical economists. However, Malthus’s work remains significant for its emphasis on the importance of demand, the social implications of economic policy, and the limitations imposed by population growth.

Impact, Legacy, and Modern Interpretations

Thomas Robert Malthus’s ideas have had a lasting impact on economics, social theory, and public policy. His theory of population growth remains one of the most influential and controversial ideas in the history of economic thought. While his predictions about the inevitable consequences of population growth have not been fully realized, his work continues to shape debates on population, resources, and sustainability.

Malthus’s influence can be seen in a wide range of fields, from economics and sociology to environmental science and public health. His ideas have been invoked in discussions about food security, poverty, and the limits of economic growth. The concept of carrying capacity, which is central to modern ecological thought, is rooted in Malthusian principles. As concerns about climate change, resource depletion, and environmental degradation grow, Malthus’s warnings about the consequences of unchecked population growth have gained renewed relevance.

In economics, Malthus’s work has influenced both classical and modern economic theory. His emphasis on the importance of effective demand anticipated later developments in Keynesian economics, which focuses on the role of aggregate demand in driving economic growth. Malthus’s ideas on rent and the distribution of resources also contributed to the development of classical economic theory, influencing economists like Ricardo and John Stuart Mill.

Malthus’s ideas have also had a significant impact on public policy, particularly in the areas of population control and poverty relief. In the 19th century, his theory was used to justify policies that aimed to limit population growth and reduce the burden on public resources. The Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834, which sought to make poor relief less attractive, was influenced by Malthusian thinking. In the 20th century, Malthus’s ideas were invoked in debates over family planning and birth control, particularly in developing countries where rapid population growth was seen as a threat to economic development.

However, Malthus’s legacy is not without controversy. His theory has been criticized for its deterministic and pessimistic outlook, as well as for its failure to account for the potential of technological innovation to overcome resource constraints. Critics argue that Malthus underestimated the capacity of human societies to adapt to changing conditions and to develop new technologies that can increase the supply of resources. The Green Revolution, for example, demonstrated that advances in agricultural technology could significantly increase food production, alleviating the pressures that Malthus had described.

Moreover, Malthus’s ideas have been associated with eugenics and other harmful policies aimed at controlling population growth. Some of his followers advocated for measures that would restrict the reproduction of certain groups, leading to ethical and moral concerns about the implications of Malthusian theory. These associations have tarnished Malthus’s legacy, particularly in the context of 20th-century population control policies that veered into coercive or ethically dubious practices. For example, some of Malthus’s ideas were misappropriated by proponents of eugenics, who argued for the selective breeding of humans to improve genetic quality. Although Malthus himself did not advocate such measures, the deterministic aspects of his theory were interpreted by others as a justification for restricting the reproduction of certain populations deemed “unfit.”

Moreover, the harsh application of Malthusian ideas has been linked to policies that exacerbated social inequality and human suffering. For instance, during the Great Irish Famine of the 1840s, some British policymakers viewed the crisis through a Malthusian lens, seeing it as a natural and inevitable consequence of overpopulation. This perspective contributed to a lack of effective intervention, as the suffering of the Irish population was considered by some to be an unavoidable outcome of Malthusian principles. These historical episodes have left a dark shadow over Malthus’s intellectual legacy, complicating his reputation as a social theorist.

In the modern era, however, Malthus’s work has experienced a resurgence, especially in discussions about environmental sustainability and global resource limits. Neo-Malthusianism, a modern reinterpretation of Malthusian ideas, emphasizes the potential for environmental degradation, resource depletion, and social instability due to unchecked population growth. This school of thought argues that while technological innovations have temporarily alleviated some of the pressures Malthus predicted, the fundamental issue of finite resources remains relevant. Neo-Malthusians warn that continued population growth, combined with rising consumption, could lead to ecological collapse unless significant changes are made to how societies manage resources.

Contemporary environmentalists and economists often invoke Malthusian concepts when discussing issues such as climate change, deforestation, water scarcity, and biodiversity loss. The notion that there are ecological limits to growth, a central theme in Malthus’s work, resonates with current concerns about the planet’s capacity to sustain human activity. Debates over the carrying capacity of the Earth, sustainable development, and the balance between population and resources all echo Malthusian ideas, albeit in a more complex and nuanced context than Malthus originally envisioned.

Malthus’s influence also extends to global public health, particularly in discussions about food security and famine. Organizations such as the United Nations and the World Food Programme frequently address the challenges posed by population growth in regions where resources are already scarce. While technological advances in agriculture, such as genetically modified crops and precision farming, have helped to feed a growing global population, the specter of Malthusian scarcity still looms in areas vulnerable to environmental changes and political instability.

Critics of modern Malthusianism argue that it remains overly pessimistic and fails to fully account for the human capacity for innovation and adaptation. They point to the historical success of technological advancements, economic reforms, and social changes in overcoming the challenges Malthus anticipated. However, even these critics acknowledge that the basic tension between population growth and resource availability—a core Malthusian concern—continues to pose significant challenges for global development and environmental sustainability.