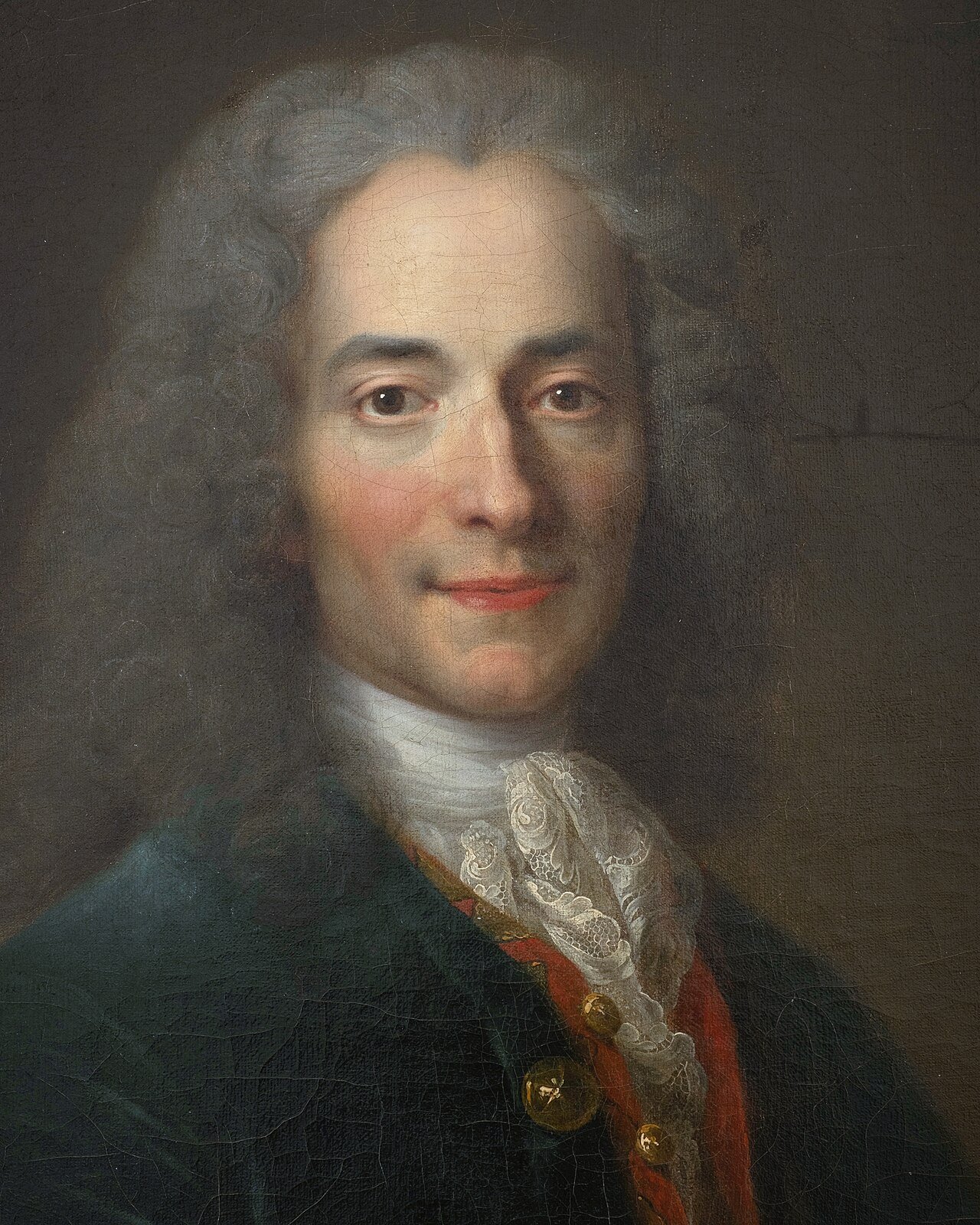

Voltaire, born François-Marie Arouet (1694–1778), was a leading French Enlightenment philosopher, writer, and critic. Renowned for his wit and advocacy of civil liberties, he championed freedom of speech, separation of church and state, and intellectual tolerance. Voltaire’s works include the famous satirical novella Candide, which critiques the philosophical optimism of his time through a series of comedic and often tragic misadventures. His sharp critiques of established institutions and his polemical writings earned him both admiration and controversy. Voltaire’s prolific output spans essays, historical works, plays, and letters, reflecting his commitment to reason and skepticism of authoritarianism. His influence extended beyond literature, shaping modern secular thought and democratic ideals, and his legacy remains significant in discussions of human rights and freedom.

Early Life and Education (1694-1717)

François-Marie Arouet, better known by his pen name Voltaire, was born on November 21, 1694, in Paris, France. He was the youngest of five children, though only two of his siblings survived to adulthood. His father, François Arouet, was a well-established notary, and his mother, Marie Marguerite Daumard, came from a minor noble family. Despite his bourgeois background, Voltaire would later cultivate an aristocratic persona, preferring the refined life of the court and salon over his middle-class origins.

Voltaire’s early education took place at the prestigious Jesuit-run Collège Louis-le-Grand in Paris. The education he received here was rigorous and classical, focusing on Latin, rhetoric, and philosophy. Voltaire excelled in his studies, showing a particular talent for literature and the classics. The Jesuits emphasized strict discipline, but also encouraged intellectual curiosity, a trait that Voltaire would carry with him throughout his life. The young Voltaire was heavily influenced by classical authors such as Virgil, Horace, and Cicero, as well as the early modern French playwrights Pierre Corneille and Jean Racine. The seeds of his later literary ambitions were sown during this period.

However, Voltaire’s relationship with his family was strained. His father hoped that he would pursue a legal career, and after completing his studies, Voltaire was sent to Caen to study law. But Voltaire’s interests lay elsewhere. He was already developing a passion for writing, and he began frequenting the literary salons of Paris, where he mingled with poets, playwrights, and philosophers. His wit, charm, and intelligence quickly earned him a place in these circles, but his sharp tongue also led to trouble. Even at a young age, Voltaire had a penchant for satire and a willingness to criticize authority, traits that would define his career.

In 1713, Voltaire’s father secured him a position as secretary to the French ambassador in the Netherlands. Although this was intended to steer him toward a more conventional career, Voltaire instead used the opportunity to immerse himself in the vibrant intellectual culture of the Dutch Republic. During his time in the Netherlands, Voltaire had a romantic entanglement with a French Protestant refugee named Catherine Olympe Dunoyer. This scandalous affair displeased his father, who promptly recalled him to France.

Returning to Paris in 1714, Voltaire continued to pursue a literary career despite his father’s disapproval. His first serious attempts at writing were poems and plays, which showcased his wit and his ability to navigate the complexities of French society. Voltaire’s early works were influenced by the neoclassical style, but he was also beginning to develop his own voice, one that would be characterized by a fierce commitment to reason and a disdain for dogma.

By 1717, Voltaire’s satirical writings had caught the attention of the French authorities. He was accused of writing verses that lampooned the regent, Philippe II, Duke of Orléans. This led to his arrest and imprisonment in the Bastille, a notorious fortress-prison in Paris. Voltaire spent nearly a year in the Bastille, but the experience did not break his spirit. Instead, it further cemented his rebellious nature and his resolve to challenge authority through his writing. It was during his imprisonment that he adopted the pen name “Voltaire,” a name that would become synonymous with Enlightenment thought.

The origin of the name Voltaire is a subject of debate. Some scholars believe it was an anagram of “Arouet, le jeune,” while others suggest it was a variation of the Latinized spelling of his family estate, “Airvault.” Regardless of its origin, the name Voltaire became emblematic of his identity as a writer and a thinker. It was under this name that he would challenge the powerful institutions of his time: the monarchy, the Church, and the aristocracy.

Voltaire’s early life and education laid the foundation for his future career as one of the most influential figures of the Enlightenment. His classical education, his exposure to the literary salons of Paris, and his early brushes with the law all contributed to shaping his worldview. Voltaire emerged from these experiences with a commitment to intellectual freedom, a sharp wit, and a determination to use his pen as a weapon against tyranny and ignorance. As he moved into his adult life, these traits would only become more pronounced, setting the stage for a remarkable career that would challenge the very foundations of European society.

Early Career and First Exile (1718-1726)

Following his release from the Bastille in 1718, Voltaire returned to the Parisian literary scene with renewed vigor. His time in prison had done little to curb his rebellious spirit, and he quickly resumed his writing, focusing on both poetry and drama. His first major success came with the tragedy Œdipe (1718), a play based on the Greek myth of Oedipus. The play was well received by both critics and the public, establishing Voltaire as a significant figure in French theater. Œdipe marked the beginning of Voltaire’s long and prolific career as a playwright, during which he would write over fifty plays.

Voltaire’s success with Œdipe brought him into contact with the aristocracy, and he began to move in higher social circles. His wit and charm made him a favorite at the court of the regent, Philippe II, Duke of Orléans. However, Voltaire’s sharp tongue and satirical writings continued to make him enemies among the powerful. In 1725, a quarrel with the Chevalier de Rohan, a powerful nobleman, led to Voltaire’s second major confrontation with the French authorities. After being insulted by Rohan, Voltaire responded with a biting retort. Enraged, Rohan had Voltaire beaten by his servants. When Voltaire demanded satisfaction, he was once again arrested and imprisoned in the Bastille.

This time, Voltaire was given a choice: he could either remain in prison or leave France. Voltaire chose exile, and in 1726, he departed for England, where he would spend the next three years. This period of exile would prove to be one of the most formative experiences of his life, exposing him to new ideas and influencing his future work in profound ways.

England in the early 18th century was a very different place from France. While France was still ruled by an absolute monarchy, England had a constitutional monarchy with a relatively free press and a more open intellectual climate. The English Enlightenment, led by thinkers such as John Locke and Isaac Newton, emphasized reason, empiricism, and the scientific method. Voltaire was deeply impressed by the intellectual freedom he found in England, as well as by the country’s political and religious tolerance.

During his time in England, Voltaire became acquainted with many of the leading intellectuals of the day, including the philosopher George Berkeley, the writer Jonathan Swift, and the poet Alexander Pope. He also studied the works of John Locke, whose ideas about the nature of human understanding and the social contract had a profound impact on Voltaire’s thinking. Locke’s emphasis on the importance of reason and the rights of the individual would become central themes in Voltaire’s later writings.

Voltaire was also deeply influenced by the work of Sir Isaac Newton, whose discoveries in physics and mathematics were revolutionizing the scientific world. Newton’s theories about gravity and the laws of motion provided Voltaire with a model of how reason and observation could be used to understand the natural world. Voltaire became one of the leading proponents of Newtonian science in France, helping to popularize Newton’s ideas on the continent.

Voltaire’s time in England also gave him a new perspective on religion. While he remained critical of organized religion, particularly the Catholic Church, he was impressed by the relative religious tolerance in England, where different sects were allowed to coexist. This contrasted sharply with the situation in France, where religious dissent was often met with persecution. Voltaire’s experiences in England reinforced his belief in the importance of religious tolerance, a theme that would feature prominently in his later works.

In 1733, after returning to France, Voltaire published Letters Concerning the English Nation (later known as Lettres philosophiques in French). This book was a collection of essays in which Voltaire praised English society for its intellectual freedom, political system, and religious tolerance. The Lettres were a thinly veiled critique of French absolutism and the Catholic Church, and they caused a sensation in France. The French authorities condemned the book, and Voltaire was once again forced to flee Paris, this time taking refuge in the chateau of the Marquise du Châtelet in Cirey, in the region of Lorraine.

The Lettres philosophiques marked a turning point in Voltaire’s career. They established him as a leading voice of the Enlightenment and set the tone for much of his future work. In these essays, Voltaire used England as a lens through which to criticize the institutions of his homeland, particularly the French monarchy and the Catholic Church. He praised the relative intellectual freedom in England, the more democratic elements of its political system, and its greater tolerance for religious diversity.

Voltaire’s admiration for England extended beyond its political and religious systems. He was also struck by the flourishing of science and philosophy in the country. During his time in England, he became acquainted with the works of scientists and philosophers like Isaac Newton and John Locke. Newton’s laws of motion and universal gravitation represented, for Voltaire, the triumph of reason and the power of the human mind to unlock the mysteries of the natural world. Locke’s writings on government and individual rights challenged the idea of absolute monarchy and emphasized the social contract, ideas that resonated deeply with Voltaire’s growing political thought.

The Lettres philosophiques were groundbreaking not only for their content but also for their style. Voltaire wrote in a clear, engaging manner that made complex philosophical ideas accessible to a broad audience. His wit and sharp critique of the French institutions were both entertaining and enlightening, ensuring the work’s popularity. However, this popularity came at a price. The book was banned by the French authorities, and Voltaire was once again forced to flee Paris. His books were burned, and a warrant was issued for his arrest.

This was not the first time Voltaire had been forced to flee, and it would not be the last. But each time, exile only served to fuel his intellectual curiosity and sharpen his critiques of authority. For the next several years, Voltaire lived with Émilie du Châtelet, a brilliant mathematician and physicist, at her chateau in Cirey. Their relationship was one of both romance and intellectual partnership. Together, they studied and wrote about science, philosophy, and literature, further refining the ideas that would make Voltaire one of the central figures of the Enlightenment.

During this period, Voltaire continued to write plays, poems, and essays, always with an eye toward challenging the status quo and promoting the ideals of reason, liberty, and tolerance. His exile in England and his experiences in French society had cemented these values as the core of his worldview, and he would spend the rest of his life advocating for them in his writings and his actions.

The impact of Voltaire’s early career and first exile cannot be overstated. By the time he returned to France, Voltaire had already established himself as a leading intellectual and a fierce critic of authority. His experiences in England had exposed him to new ideas and new ways of thinking, which he brought back to France in his writings. These early years set the stage for the rest of Voltaire’s career, during which he would become one of the most influential voices of the Enlightenment, using his wit, his pen, and his unyielding belief in reason to challenge the institutions of his time and to advocate for a more just and enlightened society.

London Exile and English Influence (1726-1729)

Voltaire’s exile in England between 1726 and 1729 was not merely a time of refuge; it was a period of profound intellectual growth that would leave a lasting impact on his philosophical outlook and future writings. England, with its relatively open society and constitutional monarchy, offered Voltaire a stark contrast to the absolutism and censorship of France. The country’s intellectual climate, brimming with the ideas of empiricism, natural philosophy, and political theory, captivated Voltaire and influenced much of his later work.

Arriving in England in May 1726, Voltaire initially faced difficulties due to his limited knowledge of the English language. Nevertheless, his intellect and charm allowed him to quickly immerse himself in London’s literary and philosophical circles. He became acquainted with prominent figures such as Jonathan Swift, Alexander Pope, and John Gay. These connections opened doors for him to engage with England’s intellectual elite, where he encountered the works of major thinkers like John Locke and Isaac Newton.

John Locke’s philosophy, particularly his ideas about empiricism and the social contract, had a profound effect on Voltaire. Locke’s assertion that human understanding is derived from experience and that government should be based on the consent of the governed resonated deeply with Voltaire, who had grown increasingly critical of the arbitrary power exercised by the French monarchy and the Catholic Church. Locke’s political theories laid the groundwork for Voltaire’s later advocacy of civil liberties and his critiques of despotism.

Similarly, Isaac Newton’s scientific achievements impressed Voltaire and reinforced his belief in the power of reason. Newton’s discoveries in physics, especially his laws of motion and universal gravitation, represented for Voltaire the triumph of human intellect over ignorance and superstition. Voltaire became an enthusiastic proponent of Newtonian science, and his efforts to popularize Newton’s work in France would play a key role in bringing the ideas of the Scientific Revolution to a broader European audience.

Voltaire’s fascination with England extended beyond philosophy and science to the country’s political system. England’s constitutional monarchy, which limited the power of the king through Parliament and protected certain individual rights, stood in stark contrast to the absolute monarchy of France. The relatively free press and the existence of political opposition also impressed Voltaire, who admired the English system for allowing more freedom of thought and expression. While England was by no means a perfect democracy, its political structure offered a model for a more balanced and just form of governance, one that Voltaire believed France should emulate.

Religious tolerance in England also caught Voltaire’s attention. Unlike in France, where Catholicism was the state religion and dissenters were often persecuted, England allowed for a greater degree of religious diversity. Although the Church of England was the established church, other Christian denominations, including Presbyterians, Baptists, and Quakers, were allowed to practice their faith relatively freely. This tolerance, while not complete, was far greater than what Voltaire had witnessed in France, where religious dissent was often met with violence and oppression. Voltaire’s experiences in England reinforced his belief in the necessity of religious tolerance, a theme that would become central to his later writings.

During his time in England, Voltaire also observed the role of commerce in shaping society. England’s growing commercial economy, driven by trade and industry, stood in contrast to the more agrarian-based economy of France. Voltaire saw in England a society where commerce encouraged innovation, progress, and social mobility, values that aligned with his Enlightenment ideals. He believed that a strong commercial class could serve as a counterbalance to the power of the aristocracy and promote greater equality and opportunity.

Voltaire’s admiration for England culminated in the publication of Letters Concerning the English Nation in 1733 (later published in France as Lettres philosophiques). This collection of essays covered a wide range of topics, including religion, politics, science, and literature, all viewed through the lens of Voltaire’s experiences in England. In these essays, Voltaire praised England’s constitutional monarchy, religious tolerance, and intellectual freedom, while implicitly criticizing the absolutism and repression of France. The Lettres philosophiques were revolutionary in their tone and content, as they challenged the dominant institutions of French society and called for reform.

The impact of the Lettres philosophiques was immediate and controversial. The French authorities quickly condemned the book as subversive, and it was banned shortly after its publication. Copies were seized and burned, and Voltaire was once again forced to flee Paris to avoid arrest. Despite the controversy, the Lettres philosophiques solidified Voltaire’s reputation as a leading intellectual of the Enlightenment and set the stage for his future work as a champion of reason, liberty, and tolerance.

Voltaire’s exile in England was a pivotal moment in his life. The ideas he encountered there—empiricism, Newtonian science, constitutional government, religious tolerance, and the importance of commerce—would become central themes in his later writings. The experience broadened his perspective and deepened his commitment to challenging the injustices of the Old Regime in France. When Voltaire returned to his homeland, he was no longer just a satirist and playwright; he had become a philosopher and an advocate for Enlightenment ideals that would shape the intellectual and political landscape of Europe for decades to come.

The Rise of Voltaire: Historical Writings and Enlightenment Thought (1730-1749)

Following his return to France after the English exile, Voltaire entered a period of significant intellectual and literary output. The years from 1730 to 1749 were marked by his transformation into a major public intellectual and a key figure in the Enlightenment movement. This period saw Voltaire’s emergence not only as a prolific writer but also as a sharp critic of contemporary society and politics.

One of Voltaire’s major achievements during this time was his extensive work in historical writing. His Histoire de Charles XII (1731) was his first major historical work, a biography of the Swedish king Charles XII. This work showcased Voltaire’s ability to blend historical analysis with engaging narrative, a style that would become a hallmark of his later works. In Histoire de Charles XII, Voltaire presented a critical and somewhat revisionist account of Charles XII’s reign, focusing on the king’s military campaigns and political decisions. The work was well received and established Voltaire’s reputation as a historian.

Voltaire’s foray into historical writing continued with Histoire de l’Empire de Russie sous Pierre le Grand (1739), a detailed account of the reign of Peter the Great of Russia. This work demonstrated Voltaire’s growing interest in the broader European context and his skill in weaving together historical facts with insightful commentary. In this history, Voltaire highlighted Peter the Great’s reforms and his role in modernizing Russia, offering a nuanced view that contrasted with the often one-sided portrayals of historical figures common in the period.

These historical writings were part of Voltaire’s broader engagement with Enlightenment thought. He became increasingly involved in philosophical debates and public discourse, championing the ideals of reason, progress, and tolerance. Voltaire’s philosophical writings during this period included Le Dictionnaire philosophique (1764), a work that compiled his thoughts on a range of subjects, from religion to politics. The Dictionnaire was notable for its clarity and its willingness to challenge established norms, making it a seminal work of the Enlightenment.

Voltaire’s engagement with Enlightenment ideas also led him to critique the existing social and political order. His Candide (1759) is perhaps the most famous of his satirical works, a novella that critiques the optimism espoused by the philosopher Leibniz and his followers. Through the character of Candide, Voltaire satirizes the idea that “all is for the best in the best of all possible worlds,” presenting a more cynical view of human suffering and the folly of blind optimism. Candide was met with both acclaim and controversy, illustrating Voltaire’s skill at provoking thought and challenging prevailing ideologies.

Voltaire’s philosophical and historical works during this period were not just limited to written texts. He was also an active participant in the salons and intellectual circles of Paris, where he engaged in debates with other Enlightenment thinkers and philosophers. His correspondence with figures such as Denis Diderot and Jean-Jacques Rousseau was instrumental in shaping the intellectual climate of the time. These exchanges helped to refine Voltaire’s ideas and to promote the principles of the Enlightenment.

In addition to his philosophical writings, Voltaire continued to produce plays and poems, although his focus increasingly shifted toward his role as a critic and commentator. His dramatic works, including Zaire (1732) and La Mort de César (1735), were well received and contributed to his reputation as a leading literary figure. However, it was his historical and philosophical writings that solidified his place in the Enlightenment movement.

The period from 1730 to 1749 was crucial in Voltaire’s development as a thinker and writer. His historical works demonstrated his ability to engage with complex subjects and to present them in an accessible and compelling manner. His philosophical writings and public discourse established him as a leading advocate of Enlightenment ideals, challenging established norms and promoting the values of reason, progress, and tolerance. Voltaire’s contributions during this time were instrumental in shaping the intellectual landscape of 18th-century Europe and in laying the groundwork for the broader Enlightenment movement.

Collaboration with Frederick the Great and Later Career (1750-1770)

In the latter half of the 18th century, Voltaire’s career took on new dimensions as he engaged in a notable collaboration with Frederick II of Prussia, known as Frederick the Great. This period, from 1750 to 1770, was marked by Voltaire’s involvement in political and diplomatic affairs, his continued literary output, and his influence on European intellectual and political life.

Voltaire first met Frederick the Great in 1736 during a visit to the Prussian court in Berlin. The two men quickly developed a mutual respect and friendship, united by their shared intellectual interests and Enlightenment ideals. Frederick, who was a great admirer of Voltaire’s work, sought to bring him to his court and to benefit from his insights and counsel.

In 1750, Voltaire accepted an invitation from Frederick to come to Berlin, where he would serve as a confidant and advisor to the king. This period of collaboration lasted until 1753, and it was marked by both intellectual engagement and personal conflict. While Frederick valued Voltaire’s contributions and saw him as an important intellectual ally, their relationship was not without its tensions.

Voltaire’s time at the Prussian court was productive. He wrote several works during this period, including La Pucelle d’Orléans (1755), a satirical poem about Joan of Arc, and L’Ingénu (1767), a philosophical tale that critiques religious and social institutions. His writing during this time continued to reflect his Enlightenment values, emphasizing reason, tolerance, and skepticism of authority.

However, the relationship between Voltaire and Frederick was strained by personal and political disagreements. Voltaire’s outspoken criticism of the Prussian court and Frederick’s policies led to tensions between the two men. In 1753, Voltaire was involved in a public quarrel with Frederick’s ministers, which resulted in his departure from Berlin and a period of travel through Europe.

Despite the difficulties in his relationship with Frederick, Voltaire’s time in Prussia had a lasting impact on his career. The experience provided him with valuable insights into the workings of an enlightened monarchy and the complexities of political power. Voltaire continued to correspond with Frederick and to engage with his ideas, contributing to the broader intellectual and political discourse of the time.

After leaving Prussia, Voltaire settled in Geneva and later in the French region of Ferney, near the Swiss border. During this period, he continued to be an active writer and public figure. His works from this time included Le Dictionnaire philosophique (1764) and L’Année de la peste (1764), which further developed his critiques of religion and politics.

Voltaire’s later career was marked by his ongoing advocacy for Enlightenment ideals and his influence on European intellectual and political life. He continued to engage in debates and correspondence with other Enlightenment thinkers and to challenge the established norms of his time. His writings and public statements contributed to the shaping of Enlightenment thought and the promotion of reason, tolerance, and progress.

The collaboration with Frederick the Great and the subsequent years of Voltaire’s career reflected both the opportunities and challenges of being a leading intellectual in an age of political and social change. Voltaire’s engagement with Frederick and his continued literary output demonstrated his commitment to the ideals of the Enlightenment and his influence on the intellectual and political landscape of 18th-century Europe.

The Legacy of Voltaire: Influence, Death, and Posterity (1770-1789)

As Voltaire entered the final decades of his life, his influence on European intellectual and political life continued to grow. The period from 1770 to his death in 1778 was marked by his enduring impact on Enlightenment thought, his continued activism, and his eventual legacy.

Voltaire’s writings and ideas had a profound effect on the intellectual climate of the time. His critiques of religion, politics, and social institutions resonated with many and contributed to the broader Enlightenment movement. His emphasis on reason, tolerance, and individual rights influenced subsequent generations of thinkers and reformers.

One of Voltaire’s most enduring contributions was his advocacy for religious tolerance and freedom of expression. His works, including Candide and Lettres philosophiques, challenged the dominance of religious orthodoxy and promoted the idea that individuals should be free to think and speak without fear of persecution. Voltaire’s defense of these principles helped to shape the modern understanding of religious freedom and laid the groundwork for later human rights movements.

In addition to his advocacy for religious tolerance, Voltaire was a prominent critic of political despotism and arbitrary power. His writings often challenged the authority of monarchs and the abuses of power by ruling elites. Voltaire’s commitment to political reform and his emphasis on the importance of reason and justice had a lasting impact on the development of democratic ideas and the promotion of constitutional government.

Voltaire’s legacy was also shaped by his influence on the French Revolution. While he did not live to see the revolution unfold, his ideas and writings were instrumental in shaping the intellectual climate that led to the revolutionary upheaval. The principles of the Enlightenment, as articulated by Voltaire and his contemporaries, played a key role in inspiring the demands for political and social change that characterized the revolution.

In the years leading up to his death, Voltaire continued to be an active and influential figure. He maintained correspondence with other Enlightenment thinkers and continued to write and speak on a range of issues. His engagement with contemporary debates and his commitment to his principles demonstrated his enduring relevance and influence.

Voltaire passed away on May 30, 1778, at the age of 83. His death marked the end of an era but also the beginning of a lasting legacy that would significantly influence European intellectual and political life. Voltaire’s passing was widely mourned, and his contributions were recognized by both contemporaries and future generations. Despite his controversial life and outspoken criticisms of various institutions, his ideas had a profound impact on the course of history. His advocacy for civil liberties, religious tolerance, and rational inquiry continued to inspire movements for reform and Enlightenment ideals across Europe.

In the immediate aftermath of his death, Voltaire’s reputation grew even more prominent. His works were celebrated for their wit, clarity, and boldness. His critique of religious intolerance, his satire against arbitrary power, and his promotion of reason and scientific inquiry became foundational elements of Enlightenment thought. The French Revolution, which erupted in 1789, was heavily influenced by the principles articulated by Voltaire and his contemporaries. Although Voltaire himself did not live to witness the revolution, his advocacy for individual rights and critical approach to authority resonated deeply with revolutionary ideals.

Voltaire’s ideas about governance and reform also found resonance in the broader European context. Enlightenment thinkers and reformers across the continent drew inspiration from his writings to challenge the existing social and political structures. His works contributed to the broader intellectual movement that sought to promote rationality, democracy, and human rights. Voltaire’s emphasis on empirical evidence and his skepticism of dogmatic beliefs helped to pave the way for the development of modern secular and democratic societies.

In addition to his influence on political thought, Voltaire’s literary legacy continued to shape literature and philosophy. His style, characterized by its sharp wit, satirical edge, and clear prose, set a standard for later writers and philosophers. His ability to blend humor with profound philosophical insights made his works both accessible and thought-provoking. Voltaire’s literary innovations, especially in satire and philosophical narrative, left a lasting mark on the development of European literature.

The years following his death saw a growing recognition of Voltaire’s contributions to intellectual history. Monuments were erected in his honor, and his works were studied and celebrated by scholars and students. His influence extended beyond France, impacting intellectual and cultural life in other European countries. Voltaire’s writings were translated into various languages and continued to be read and discussed across the continent.

In addition to his literary and philosophical impact, Voltaire’s life and work were also the subject of extensive biographical and critical studies. Scholars and historians examined his contributions to Enlightenment thought and his role in shaping the intellectual landscape of the 18th century. His correspondence with other leading figures of the Enlightenment, as well as his interactions with political leaders and institutions, were explored to understand his influence and legacy more fully.

Voltaire’s life and ideas continue to be relevant in contemporary discussions about freedom of expression, religious tolerance, and human rights. His commitment to questioning authority and advocating for rational discourse remains a powerful example for those who seek to challenge injustice and promote enlightenment values. As a central figure of the Enlightenment, Voltaire’s legacy endures through his writings, his influence on subsequent thinkers, and his impact on the development of modern democratic and secular ideals.