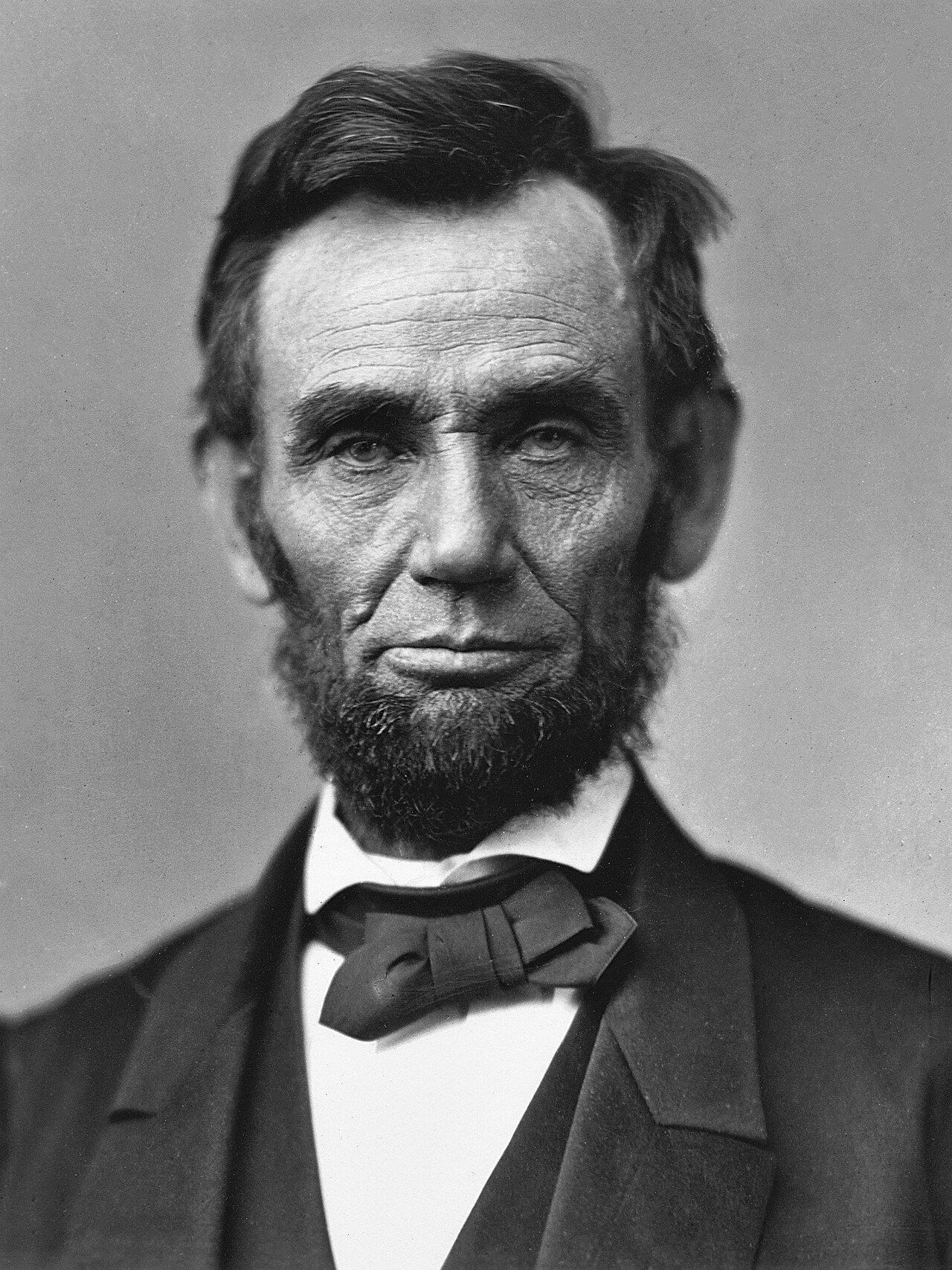

Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865) was the 16th President of the United States, serving from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Born in a log cabin in Kentucky, Lincoln rose from modest beginnings to become a key figure in American history. His presidency was defined by the American Civil War, a conflict that tested the nation’s commitment to its founding principles. Lincoln is renowned for his leadership in preserving the Union and his efforts to end slavery, most notably through the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, which declared all enslaved people in Confederate-held territory to be free. He also delivered the Gettysburg Address in 1863, a speech that articulated the war’s purpose and redefined the nation’s ideals. Lincoln’s legacy is marked by his dedication to equality, democracy, and the preservation of the United States, making him one of the most revered leaders in American history.

Early Life and Education (1809–1830)

Abraham Lincoln was born on February 12, 1809, in a one-room log cabin on the Sinking Spring Farm in Hardin County, Kentucky, which is now part of LaRue County. He was the second child of Thomas Lincoln and Nancy Hanks Lincoln, two uneducated farmers. Lincoln’s early years were marked by hardship and poverty, which would shape his character and values for the rest of his life. His early life was defined by a series of moves and challenges that would influence his later worldview.

Thomas Lincoln, Abraham’s father, was a hard-working but unambitious farmer and carpenter who struggled to make ends meet. The family moved frequently due to land disputes and other difficulties. In 1811, they moved to a farm on Knob Creek, but faced legal disputes over the land. By 1816, frustrated with legal issues and seeking better opportunities, Thomas moved his family to the wilderness of southern Indiana, where they lived in a crude shelter until a more permanent home was built. It was in Indiana that young Abraham would experience both profound loss and personal growth.

In 1818, tragedy struck the Lincoln family when Nancy Hanks Lincoln died of “milk sickness,” a disease caused by drinking milk from cows that had ingested poisonous white snakeroot. Her death left a deep emotional scar on nine-year-old Abraham. Thomas Lincoln remarried the following year, bringing a widow named Sarah Bush Johnston and her three children into the household. Sarah Bush Lincoln was a kind and affectionate stepmother who encouraged Abraham’s curiosity and learning. She quickly bonded with Abraham, who came to regard her with great affection, referring to her as “Mother.” Under her care, Abraham found some stability and solace, though the challenges of frontier life were never far away.

Abraham Lincoln’s formal education was limited and sporadic. Over the course of his youth, he received only about 18 months of formal schooling, spread out over several years. The schools he attended were typically “blab schools,” where students repeated lessons aloud. Nevertheless, Lincoln was an eager learner and voracious reader. He borrowed books whenever he could, teaching himself through the works of authors like Aesop, the Bible, John Bunyan, and William Shakespeare. His stepmother Sarah would later remark that Abraham “read every book he could lay his hands on.”

Despite his limited schooling, Lincoln developed a reputation for being intelligent and thoughtful. He was known for his storytelling ability and his talent for mimicry, often entertaining his friends and family with his stories and imitations. His intellectual curiosity, combined with a growing awareness of the world beyond the frontier, set him apart from his peers. The frontier environment, with its demand for manual labor and self-reliance, further shaped Lincoln’s character. He became skilled in the use of an ax and was known for his strength and ability to work hard. Yet, he never lost his desire for knowledge and learning, and he used any spare time he had to read and study.

As Lincoln grew into his teenage years, he developed a sense of moral integrity and a dislike for cruelty and injustice. His experiences working on the family farm, as well as hired labor for neighbors, gave him an understanding of the harsh realities of life and labor. He also witnessed the effects of slavery firsthand during a trip to New Orleans in 1828, where he encountered slaves being bought and sold. The experience left a lasting impression on him and would later influence his views on slavery.

By the time Lincoln turned 21 in 1830, his family moved again, this time to Illinois. Thomas Lincoln had once more decided to seek better opportunities, and the family settled on a farm in Macon County, near Decatur. Abraham, however, was now of age and increasingly independent. He assisted in building the new family home and worked to help clear land, but his thoughts were turning toward a different future. The move to Illinois marked a turning point in Lincoln’s life, as he began to seek opportunities beyond the farm. His early years had instilled in him a deep sense of responsibility, a desire for self-improvement, and a commitment to principles that would guide him for the rest of his life.

Early Career and Entry into Politics (1830–1849)

In the spring of 1831, after helping his family settle in Illinois, Abraham Lincoln struck out on his own. He found work on a flatboat, transporting goods down the Mississippi River to New Orleans. This journey was pivotal for Lincoln, as it exposed him to the broader world and deepened his abhorrence of slavery after witnessing a slave auction in the South. Upon his return, he settled in the small village of New Salem, Illinois, where he would spend the next several years of his life.

New Salem was a formative period for Lincoln. He worked a variety of jobs, including as a clerk in a general store, a postmaster, and a surveyor. These experiences broadened his horizons and deepened his understanding of people and their concerns. His honesty, integrity, and storytelling abilities won him the respect and friendship of the local community. It was during this time that Lincoln began to educate himself more formally, studying law, grammar, and mathematics. His self-discipline and determination were evident as he pursued knowledge despite his lack of formal schooling.

In 1832, Lincoln’s burgeoning political interests took shape when he decided to run for the Illinois General Assembly. However, his campaign was interrupted by the outbreak of the Black Hawk War, in which he volunteered for service. Lincoln was elected captain of his company, a role he took seriously despite his lack of military experience. Although he did not see combat, his leadership during the conflict earned him the respect of his men and provided him with valuable experience.

After the war, Lincoln resumed his campaign but was defeated in the election. Despite this setback, he was undeterred. He began to study law more earnestly and continued to build connections in the community. Two years later, in 1834, he successfully ran for the Illinois General Assembly as a member of the Whig Party. This victory marked the beginning of Lincoln’s political career, one that would see him rise from a small-town lawyer to the highest office in the land.

As a legislator, Lincoln quickly established himself as a hard-working and astute representative. He aligned himself with the Whig Party’s platform, which supported internal improvements, a national bank, and protective tariffs. Lincoln was particularly interested in infrastructure projects, such as the construction of roads and canals, which he believed were essential for economic growth. His support for these projects reflected his belief in the importance of a modern, interconnected economy, and his legislative work focused on advancing these goals.

During his time in the Illinois General Assembly, Lincoln also began to develop his legal career. In 1836, after passing the bar exam, he received his law license and moved to Springfield, Illinois, in 1837 to establish a law practice. His partnership with John T. Stuart, a fellow legislator, proved to be successful, and Lincoln quickly gained a reputation as a skilled and ethical lawyer. His practice covered a wide range of cases, from debt collection to criminal defense, and he traveled extensively across the state to represent clients.

Lincoln’s legal career was marked by his methodical approach, his ability to simplify complex issues, and his commitment to justice. He was known for his ability to connect with juries through his clear and logical arguments, as well as his use of humor and storytelling. His honesty earned him the nickname “Honest Abe,” and he became well-respected within the legal community. His legal work not only provided him with financial stability but also deepened his understanding of the law and the American legal system.

Throughout the 1830s and 1840s, Lincoln continued to serve in the Illinois General Assembly, where he gained experience in state politics and developed a network of political allies. He became a leader within the Whig Party and was known for his moderate views and pragmatic approach to issues. One of his most notable legislative achievements was his role in moving the state capital from Vandalia to Springfield in 1839, a move that benefited his home city and solidified his standing in state politics.

In 1842, Lincoln’s personal life took a significant turn when he married Mary Todd, a well-educated and politically connected woman from a prominent Kentucky family. Their courtship had been tumultuous, with Lincoln breaking off their engagement at one point due to doubts and depression. However, they eventually reconciled and were married on November 4, 1842. The marriage brought Lincoln into a new social circle and provided him with a partner who was deeply interested in politics and supportive of his ambitions.

The 1840s also saw Lincoln’s political ambitions extend to the national stage. In 1846, he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, where he served a single term. During his time in Congress, Lincoln was a vocal critic of the Mexican-American War, which he viewed as an unjust conflict initiated by President James K. Polk. His opposition was rooted in his belief that the war was an effort to expand slavery into new territories. However, his stance was unpopular with many of his constituents, and he chose not to seek re-election.

After his term in Congress ended in 1849, Lincoln returned to Springfield to resume his law practice. He remained politically active but was largely focused on his legal career. It was during this period that Lincoln honed his skills as an orator and deepened his understanding of the issues that would later define his presidency. His early career and entry into politics laid the foundation for his rise as a national leader, and his experiences during these years shaped his views on democracy, law, and justice.

The Road to the Presidency (1850–1860)

The decade of the 1850s was a transformative period in Abraham Lincoln’s life, both personally and politically. After his return to Springfield following his single term in Congress, Lincoln immersed himself in his law practice, which had become one of the most successful in Illinois. However, it was the intensifying national debate over slavery that would draw him back into the political arena and set him on the path to the presidency.

The passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854 was the event that reignited Lincoln’s political career. Sponsored by Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, the act effectively repealed the Missouri Compromise by allowing the residents of Kansas and Nebraska to determine whether to allow slavery within their borders through popular sovereignty. Lincoln was outraged by this legislation, viewing it as a dangerous expansion of slavery that threatened the nation’s moral fabric and its future as a free society. In response, he began speaking out against the act, marking his return to public life with a series of powerful speeches that articulated his opposition to the spread of slavery.

Lincoln’s opposition to the Kansas-Nebraska Act was not just a matter of political strategy; it was deeply rooted in his moral beliefs. He saw slavery as a profound injustice, fundamentally incompatible with the principles of liberty and equality espoused by the Founding Fathers. However, Lincoln was also a pragmatist. He did not call for the immediate abolition of slavery where it already existed, recognizing that the Constitution protected it in the Southern states. Instead, he advocated for halting its expansion, believing that if slavery were confined to its current boundaries, it would eventually die out. This position allowed him to appeal to a broad spectrum of Northerners who were uncomfortable with slavery’s expansion but not yet ready to endorse abolition.

Lincoln’s emergence as a leading voice against the Kansas-Nebraska Act led to his involvement in the formation of the Republican Party, a new political coalition dedicated to opposing the spread of slavery. The Republican Party quickly gained momentum, drawing support from former Whigs, Free Soilers, and anti-slavery Democrats. Lincoln’s eloquence and moral clarity made him a natural leader within the party, and he was soon considered a potential candidate for higher office.

The Lincoln-Douglas debates of 1858 were a critical moment in Lincoln’s rise to national prominence. That year, Lincoln challenged Stephen A. Douglas for his U.S. Senate seat. Although Lincoln and Douglas had been political rivals for years, the stakes were higher than ever. The nation was increasingly divided over the issue of slavery, and the debates between Lincoln and Douglas attracted national attention. Over the course of seven debates, held in various towns across Illinois, Lincoln and Douglas clashed over the future of slavery in America.

Lincoln’s arguments during the debates were grounded in his belief that slavery was morally wrong and that it should not be allowed to spread into the territories. He famously declared, “A house divided against itself cannot stand. I believe this government cannot endure permanently half slave and half free.” This statement reflected Lincoln’s conviction that the nation would eventually have to choose between becoming entirely free or entirely slave-holding; it could not continue indefinitely as a house divided. Douglas, on the other hand, defended his doctrine of popular sovereignty, arguing that each territory should have the right to decide the slavery question for itself.

Although Lincoln ultimately lost the Senate race to Douglas, the debates elevated his national profile. His clear articulation of the moral and political stakes in the slavery debate earned him widespread recognition within the Republican Party and beyond. Many Republicans saw in Lincoln a principled and effective advocate who could unite the party and appeal to a broad electorate. His defeat in the Senate race was, paradoxically, a significant step toward his eventual nomination for the presidency.

The political landscape in the late 1850s was increasingly polarized, with the issue of slavery driving a wedge between North and South. The Dred Scott decision in 1857, in which the Supreme Court ruled that African Americans could not be citizens and that Congress had no authority to prohibit slavery in the territories, further inflamed tensions. Lincoln strongly opposed the ruling, arguing that it undermined the principles of the Declaration of Independence and threatened to make slavery a national institution. He believed that the decision was part of a conspiracy to extend slavery across the entire nation, and he used his growing platform to rally opposition to it.

In the years leading up to the 1860 presidential election, Lincoln continued to hone his political message. He delivered a number of speeches that clarified his position on slavery, emphasizing both its moral wrongness and the danger it posed to the nation’s future. His Cooper Union Address in New York City in February 1860 was particularly significant. In this speech, Lincoln carefully argued that the Founding Fathers had intended to limit the spread of slavery, not allow its expansion, and that the federal government had the authority to do so. The speech was well-received and helped to solidify Lincoln’s reputation as a thoughtful and moderate leader capable of guiding the nation through its deepening crisis.

The Republican National Convention of 1860 was held in Chicago, and Lincoln entered the convention as a dark horse candidate. The front-runner was William H. Seward, a U.S. Senator from New York and a leading abolitionist. However, Seward was seen by some as too radical, while other potential candidates had regional appeal but lacked broad national support. Lincoln’s combination of moderate anti-slavery views, strong oratory skills, and humble background made him an appealing compromise candidate. His team, led by David Davis and others, skillfully managed his campaign at the convention, securing key delegate support.

On the third ballot, Lincoln won the Republican nomination for president. His selection was a testament to his ability to navigate the complex political landscape and his growing stature within the party. The general election campaign was contentious and marked by the deep divisions in the country. The Democratic Party was split between Northern Democrats, who supported Stephen Douglas, and Southern Democrats, who backed John C. Breckinridge. A fourth candidate, John Bell of the Constitutional Union Party, also entered the race, hoping to appeal to moderates who wanted to avoid disunion.

Lincoln’s campaign was focused on the key battleground states in the North, where he emphasized his opposition to the spread of slavery while reassuring voters that he did not intend to interfere with slavery where it already existed. The Republican platform called for economic development, including support for a transcontinental railroad and protective tariffs, which appealed to Northern voters. Lincoln himself did not campaign actively, following the tradition of the time, but his supporters and the Republican press worked tirelessly on his behalf.

On November 6, 1860, Abraham Lincoln was elected the 16th President of the United States with less than 40% of the popular vote but a decisive majority in the Electoral College. His victory was met with jubilation in the North and outrage in the South. Lincoln’s election, without the support of a single Southern state, underscored the deep sectional divide in the country. Southern leaders, who had long warned that they would secede if a Republican were elected president, now began to make good on their threats. The road to the presidency had been long and difficult for Lincoln, but the challenges that awaited him as president would be far greater. The nation was on the brink of civil war, and Lincoln’s leadership would be tested as never before.

The Election of 1860 and the Start of the Civil War (1860–1861)

Abraham Lincoln’s election as the 16th President of the United States on November 6, 1860, was a pivotal moment in American history, marking the culmination of decades of sectional conflict over slavery and setting the stage for the Civil War. His victory, achieved without the support of a single Southern state, sent shockwaves through the South, where the prospect of a Republican president who opposed the expansion of slavery was seen as an existential threat to the Southern way of life. The election of 1860 was not just a political contest; it was a referendum on the future of the nation.

The 1860 election was one of the most contentious and consequential in American history. The country was deeply divided along sectional lines, with slavery at the heart of the conflict. The Democratic Party, once a national coalition that included both Northern and Southern factions, had fractured into two separate camps. The Northern Democrats, led by Stephen A. Douglas, supported popular sovereignty, which allowed territories to decide for themselves whether to permit slavery. The Southern Democrats, led by Vice President John C. Breckinridge, demanded federal protection for slavery in the territories. A fourth candidate, John Bell of the Constitutional Union Party, sought to appeal to moderates who wished to avoid disunion by ignoring the slavery issue altogether and focusing on preserving the Union.

Lincoln’s Republican platform was clear: no extension of slavery into the territories, protection of free labor, and support for infrastructure improvements. The Republicans did not call for the immediate abolition of slavery where it already existed, but they were firmly opposed to its spread. This position won Lincoln the support of many Northerners who were uneasy about slavery’s expansion but were not yet committed to abolition. The Republican Party also appealed to a broad coalition of voters by advocating for economic modernization, including a transcontinental railroad, protective tariffs, and free homesteads for settlers.

As the election approached, Southern leaders issued dire warnings about the consequences of a Lincoln victory. They argued that his election would be tantamount to a declaration of war on the South. In the months leading up to the election, there were widespread threats of secession if Lincoln were to win. These threats were not mere bluster; they reflected a genuine belief among many Southerners that their way of life, which was inextricably linked to slavery, was under imminent threat. For Lincoln, the prospect of disunion was a grave concern, but he remained committed to his principles, believing that the Union could not endure if it were to allow the unchecked expansion of slavery.

When the votes were counted, Lincoln won a decisive victory in the Electoral College, securing 180 out of 303 electoral votes. However, he received only about 40% of the popular vote, reflecting the deep divisions in the country. Lincoln carried nearly all of the Northern states, while Breckinridge won most of the South, Douglas took Missouri, and Bell won in Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee. The results underscored the sectional divide: Lincoln had won without carrying a single Southern state. For many Southerners, this was proof that their voices no longer mattered in a Union dominated by the North.

The response in the South was swift and ominous. Even before Lincoln’s inauguration, Southern states began to secede from the Union. On December 20, 1860, South Carolina became the first state to secede, declaring that it had the right to leave the Union in defense of its sovereignty and its institution of slavery. In the following weeks, six more states—Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas—also seceded, forming the Confederate States of America in February 1861. The Confederacy, led by President Jefferson Davis, adopted a constitution that closely resembled the U.S. Constitution but explicitly protected the institution of slavery and emphasized states’ rights.

As the secession crisis unfolded, President James Buchanan, who was still in office until Lincoln’s inauguration in March 1861, took little action to stop the Southern states from leaving the Union. Buchanan believed that the federal government had no authority to coerce states back into the Union, and his inaction only emboldened the secessionists. Meanwhile, efforts at compromise, such as the Crittenden Compromise, which proposed constitutional amendments to protect slavery in the territories south of the 36°30′ line, failed to gain traction. Lincoln, while supportive of efforts to maintain peace, remained firm in his opposition to any compromise that would allow the expansion of slavery.

As the seceding states seized federal forts and arsenals within their borders, tensions continued to rise. The situation was particularly volatile at Fort Sumter, a federal fort in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina. By the time Lincoln took office on March 4, 1861, Fort Sumter was one of the last remaining federal outposts in the Confederacy. The Confederate government demanded its surrender, but Major Robert Anderson, the Union commander at the fort, refused. The situation at Fort Sumter became the first major test of Lincoln’s presidency and his commitment to preserving the Union.

In his inaugural address, Lincoln sought to calm fears and prevent further secession. He reassured the South that he had no intention of interfering with slavery where it existed but made it clear that he would not recognize the secession of the Southern states or allow them to break up the Union. “In your hands, my dissatisfied fellow countrymen, and not in mine, is the momentous issue of civil war,” Lincoln declared. “The government will not assail you. You can have no conflict without being yourselves the aggressors.” Despite his conciliatory tone, Lincoln’s refusal to accept secession set the stage for an inevitable clash.

The standoff at Fort Sumter could not be resolved peacefully. On April 12, 1861, Confederate forces under General P.G.T. Beauregard opened fire on the fort, marking the beginning of the Civil War. After 34 hours of bombardment, Major Anderson surrendered Fort Sumter to the Confederates. The attack on Fort Sumter galvanized the North and solidified Lincoln’s resolve to preserve the Union. On April 15, he issued a call for 75,000 volunteers to suppress the rebellion, marking the official start of the war.

The firing on Fort Sumter also had a profound impact on the remaining slave states that had not yet seceded. In the wake of the attack, Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina joined the Confederacy, bringing the total number of Confederate states to eleven. The war, which many had hoped to avoid or at least contain, was now a reality. Both sides began to mobilize for a conflict that would ultimately last four years and claim the lives of over 600,000 Americans.

For Lincoln, the outbreak of the Civil War was both a challenge and an opportunity. He understood that the war was not just about preserving the Union; it was also about defining the future of the nation. Would the United States remain a house divided, half slave and half free, or would it emerge from the conflict as a nation committed to the principles of liberty and equality? Lincoln’s leadership during this critical period would be tested as never before, and his decisions in the months and years to come would shape the course of American history.

As the war began, Lincoln faced the daunting task of leading a divided nation through its greatest crisis. He had to balance the demands of war with the need to maintain public support, navigate the complexities of military strategy, and manage the often fractious relationships within his own government. Moreover, he had to contend with the issue of slavery, which lay at the heart of the conflict. How Lincoln addressed these challenges would determine not only the outcome of the war but also the future of the United States as a unified nation.

Lincoln’s Leadership During the Civil War (1861–1865)

Abraham Lincoln’s presidency during the Civil War is often regarded as one of the most critical periods in American history. His leadership, decisions, and vision were instrumental in navigating the country through its most profound crisis. The Civil War was not only a battle over the future of slavery but also a test of the endurance of the Union itself. Lincoln’s resolve, his ability to adapt to changing circumstances, and his moral clarity would define his presidency and ultimately determine the fate of the United States.

When the Civil War began in 1861, Lincoln faced a multitude of challenges. The Confederacy was determined and well-prepared, with strong leadership under President Jefferson Davis and General Robert E. Lee. The Union, on the other hand, was initially disorganized, lacking both a coherent military strategy and effective leadership. Lincoln, who had little military experience, had to learn quickly how to conduct a war while also managing the complex political landscape. His first task was to assemble a capable team of military and civilian leaders who could help guide the Union war effort.

One of Lincoln’s early challenges was finding the right generals to lead the Union Army. His initial choices, including General George McClellan, proved disappointing. McClellan was overly cautious, often reluctant to engage the Confederate forces despite having superior numbers. Lincoln’s frustration with McClellan grew over time, especially after the general’s failure to pursue Lee’s army following the Battle of Antietam in September 1862, which, despite being a tactical draw, was a strategic victory for the Union. Eventually, Lincoln replaced McClellan with a series of commanders, each of whom failed to deliver the decisive victories the Union needed. It was not until Lincoln appointed General Ulysses S. Grant as commander of all Union armies in 1864 that he found a leader who shared his determination to fight a total war aimed at destroying the Confederate military and its resources.

Lincoln’s approach to the war evolved as the conflict progressed. Initially, he focused on preserving the Union and restoring the nation to its pre-war status. However, as the war dragged on and casualties mounted, it became clear that the conflict was about more than just reunification; it was also about the future of slavery in America. The issue of emancipation was complex and politically sensitive. Many in the North, including some of Lincoln’s own party members, were not initially in favor of immediate abolition, while others, particularly the Radical Republicans, pushed for more aggressive action against slavery.

Lincoln’s views on slavery had always been morally opposed, but he had been cautious about pushing for abolition too quickly, fearing it would alienate the border states and undermine the war effort. However, by mid-1862, he recognized that emancipation could be a powerful tool in weakening the Confederacy and bolstering the Union cause. Following the Union’s tactical victory at Antietam, Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862, which declared that all slaves in Confederate-held territory would be free as of January 1, 1863, if the rebellion did not end by then. The Emancipation Proclamation was a bold and controversial move, but it fundamentally changed the nature of the war, transforming it into a fight not just for the Union but also for human freedom.

The Emancipation Proclamation had significant effects both at home and abroad. In the Confederacy, it undermined the Southern economy, which was heavily dependent on slave labor. It also encouraged enslaved people to flee to Union lines, weakening the Confederate war effort. In the North, the proclamation galvanized abolitionist support and made the war a moral crusade. Internationally, the proclamation had a profound impact, effectively ending any hopes the Confederacy had of gaining recognition from European powers such as Britain and France, both of which had strong anti-slavery sentiments.

Despite the importance of the Emancipation Proclamation, it did not immediately free all slaves. Its scope was limited to areas under Confederate control, leaving slavery untouched in the border states and parts of the South already occupied by Union forces. Lincoln understood that a more comprehensive solution was needed, which led him to support the passage of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution. This amendment, which would permanently abolish slavery throughout the United States, became a central focus of Lincoln’s efforts in the final months of the war. Despite significant opposition, particularly from Democrats who feared the social and economic consequences of abolition, Lincoln’s persistent advocacy helped secure the amendment’s passage in the House of Representatives in January 1865. The 13th Amendment was ratified later that year, ensuring that slavery would never again exist in the United States.

Throughout the war, Lincoln also had to manage a fractious political environment. He faced opposition not only from Southern sympathizers and Democrats but also from within his own Republican Party. The Radical Republicans, led by figures such as Thaddeus Stevens and Charles Sumner, often criticized Lincoln for being too moderate, particularly on the issue of slavery. They pushed for more aggressive measures against the South and greater protections for African Americans. On the other hand, more conservative Republicans and Union Democrats sometimes viewed Lincoln’s policies as too radical and were concerned about the implications of emancipation and the centralization of federal power.

Lincoln’s ability to navigate these political challenges was one of his greatest strengths. He was a master of political compromise and had a keen sense of timing. While he was willing to make concessions when necessary, he never wavered from his ultimate goal of preserving the Union and ending slavery. His re-election in 1864, which many had doubted would be possible given the ongoing war and the heavy toll it was taking on the nation, was a testament to his leadership. Lincoln’s decision to run on a National Union ticket with Democrat Andrew Johnson as his vice-presidential candidate was a shrewd move that broadened his appeal and helped secure victory.

The election of 1864 was held during some of the most critical moments of the war. By then, the Union had gained significant momentum, with key victories at Gettysburg, Vicksburg, and Atlanta. These successes, combined with Lincoln’s commitment to seeing the war through to a successful conclusion, resonated with voters. However, the election was still highly contested, and Lincoln feared defeat, especially as the war dragged on and casualties mounted. His opponent, former General George McClellan, ran on a platform that called for a negotiated peace with the Confederacy, which many Northerners found appealing after years of brutal conflict. Nevertheless, Lincoln’s determination to continue the fight until the Union was restored, and slavery was abolished, carried the day, and he won re-election with a substantial margin in the Electoral College.

As the war entered its final phase, Lincoln’s attention turned to the question of how to reunite the nation and heal the wounds of conflict. His vision for Reconstruction was guided by a desire for reconciliation and a belief in a “malice toward none” approach. He favored a lenient policy that would allow Southern states to rejoin the Union quickly and with minimal punishment, provided they accepted the end of slavery and pledged loyalty to the United States. This approach was in stark contrast to the more punitive measures advocated by the Radical Republicans, who sought to reshape Southern society and ensure full rights for the newly freed African Americans.

Tragically, Lincoln would not live to see his vision for Reconstruction realized. On April 9, 1865, General Robert E. Lee surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House, effectively ending the Civil War. Just five days later, on April 14, 1865, Lincoln was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth while attending a play at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C. His death was a devastating blow to the nation, which had looked to him for guidance and leadership in the difficult task of rebuilding a shattered Union.

Lincoln’s leadership during the Civil War was characterized by his steadfast commitment to the Union, his evolving views on slavery, and his remarkable ability to manage both the military and political aspects of the conflict. He navigated the complexities of war with a deep sense of moral purpose and a pragmatic approach to the challenges he faced. His legacy as a leader who preserved the Union and laid the groundwork for the abolition of slavery remains one of the most enduring in American history.

Certainly! Here is a section on “Emancipation and the Fight for Freedom (1862–1865)” that fits within the broader context of Abraham Lincoln’s biography:

Emancipation and the Fight for Freedom (1862–1865)

The Emancipation Proclamation is one of Abraham Lincoln’s most significant and celebrated achievements. Issued in two parts in 1862 and 1863, it marked a turning point in the Civil War, transforming the conflict from a struggle for the Union into a battle for human freedom. The fight for emancipation was fraught with political, social, and military challenges, but Lincoln’s leadership and moral vision ultimately guided the nation toward the abolition of slavery.

At the start of the Civil War, Lincoln’s primary goal was to preserve the Union. Although he personally abhorred slavery, he approached the issue cautiously, aware that too aggressive a stance could alienate the border states—slave states that remained loyal to the Union—and undermine the war effort. Early in the conflict, Lincoln was more focused on maintaining national unity than on ending slavery outright. He hoped that a combination of military pressure and compensated emancipation (paying slaveholders to free their slaves) would gradually lead to the institution’s demise.

However, as the war dragged on, Lincoln began to recognize that slavery was not just a moral blight but also a significant strategic factor in the Confederacy’s strength. The Southern economy relied heavily on slave labor, and the Confederacy used enslaved people to support its war effort by providing food, building fortifications, and performing other essential tasks. By striking at the institution of slavery, Lincoln could weaken the Confederacy militarily and economically while also appealing to anti-slavery sentiment in the North and among European powers.

The tipping point came in the summer of 1862. Despite some Union victories, the war had reached a stalemate, and Lincoln faced mounting pressure from Radical Republicans and abolitionists to take decisive action against slavery. At the same time, the prospect of European intervention on behalf of the Confederacy loomed large. Britain and France, though officially neutral, had economic and political interests that could have led them to recognize the Confederacy if they believed it could win the war. Lincoln understood that aligning the Union with the cause of freedom would make it politically impossible for these nations—both of which had abolished slavery—to support the Confederacy.

After much deliberation, Lincoln decided to issue an emancipation order. However, he needed a military victory to lend credibility to such a proclamation and prevent it from appearing as an act of desperation. This opportunity came with the Battle of Antietam in September 1862, where Union forces halted General Robert E. Lee’s invasion of the North. Although not a decisive victory, it was enough for Lincoln to move forward.

On September 22, 1862, Lincoln issued the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. This document declared that if the Confederacy did not cease its rebellion by January 1, 1863, all slaves in Confederate-held territory would be “then, thenceforward, and forever free.” The preliminary proclamation was a bold and controversial move, signaling Lincoln’s shift from a policy of containment to one of direct confrontation with the institution of slavery. It also gave the Confederacy an ultimatum: return to the Union or face the destruction of slavery.

When the Confederacy refused to yield, Lincoln followed through with the final Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. This executive order declared the freedom of all enslaved people in Confederate-controlled areas. While the proclamation did not immediately free a single slave—since it applied only to areas outside Union control—it fundamentally changed the character of the war. The Union army became an agent of liberation, with each advance into Southern territory bringing freedom to thousands of enslaved people.

The Emancipation Proclamation had profound implications for the war effort. It allowed African Americans to enlist in the Union army, a decision that had both symbolic and practical significance. By the end of the war, nearly 200,000 African American soldiers and sailors had served in the Union forces, playing a crucial role in achieving victory. Their bravery and sacrifices not only helped to win the war but also challenged deeply entrenched racist attitudes in the North. The inclusion of black soldiers also underscored the Union’s commitment to a more inclusive vision of freedom.

Internationally, the proclamation had an immediate and significant impact. It effectively ended any hopes the Confederacy had of gaining formal recognition from European powers. By making the abolition of slavery a central war aim, Lincoln ensured that Britain and France, which had both outlawed slavery, would find it politically untenable to support the South. The proclamation helped to align the Union cause with the global movement for human rights and liberty.

Domestically, the Emancipation Proclamation was met with mixed reactions. While abolitionists and many Northerners celebrated the move, others criticized it as either too radical or insufficient. In the South, the proclamation was denounced as a tyrannical act designed to incite slave rebellions and destroy Southern society. Within the Union, Democrats, especially those in border states and areas with strong anti-abolition sentiment, accused Lincoln of overstepping his constitutional authority and turning the war into a campaign for racial equality. Despite these criticisms, the proclamation solidified Lincoln’s reputation as the “Great Emancipator” and set the stage for the eventual abolition of slavery nationwide.

Lincoln knew that the Emancipation Proclamation, as an executive order, was limited in its permanence and scope. To ensure that slavery would be abolished forever, he pushed for the passage of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution. This amendment, which was passed by Congress in January 1865 and ratified by the states later that year, permanently outlawed slavery throughout the United States. Lincoln’s advocacy for the amendment in the final months of his life demonstrated his unwavering commitment to the cause of freedom and equality.

The fight for emancipation was not merely a legal or military struggle but also a moral one. Throughout the process, Lincoln’s views on slavery and race evolved. Initially focused on preserving the Union above all else, he came to see the war as an opportunity to address the nation’s original sin of slavery. His speeches during this period, including the Gettysburg Address and his second inaugural address, reflected his growing conviction that the war was a divine judgment on a nation that had allowed slavery to flourish. In these speeches, Lincoln articulated a vision of a nation “conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.”

The Emancipation Proclamation and the eventual abolition of slavery were monumental achievements, but they also left unresolved the broader issues of racial equality and civil rights. While Lincoln took significant steps toward a more just society, his assassination in April 1865 cut short his plans for Reconstruction. The post-war era would see significant gains for African Americans, including the passage of the 14th and 15th Amendments, but also a fierce backlash in the form of Jim Crow laws and segregation.

Lincoln’s Assassination and Legacy (1865–Present)

Abraham Lincoln’s assassination on April 14, 1865, marked a tragic end to a presidency that had guided the United States through its most perilous period. Just days after the Civil War had effectively ended with General Robert E. Lee’s surrender, Lincoln fell victim to an assassin’s bullet, leaving the nation in mourning and profoundly altering the course of American history. The circumstances surrounding his assassination, the immediate aftermath, and the long-term impact of his presidency continue to resonate in American culture, politics, and society.

Lincoln was shot by John Wilkes Booth, a well-known actor and Confederate sympathizer, at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C. Booth, angered by the defeat of the Confederacy and Lincoln’s plans to extend voting rights to certain African Americans, had originally plotted to kidnap the president. However, as the Confederacy’s prospects dimmed, Booth shifted his plans to assassination, believing that by killing Lincoln and other key officials, he could throw the federal government into disarray and revive the Southern cause. On the evening of April 14, while Lincoln was watching a performance of Our American Cousin, Booth slipped into the presidential box and shot Lincoln in the head. Lincoln was carried across the street to a boarding house, where he died the next morning on April 15, 1865.

The assassination stunned the nation. Lincoln had become a symbol of hope, unity, and moral resolve, and his death was a devastating blow to a country still reeling from the costs of the Civil War. The mourning for Lincoln was widespread and deeply felt. His body was taken on a two-week train journey from Washington, D.C., to his final resting place in Springfield, Illinois, stopping in major cities along the way. Millions of Americans paid their respects as his funeral train passed through the North, and the profound grief expressed during this period reflected the deep connection many felt with Lincoln as both a leader and a symbol of national unity.

Booth’s assassination plot was broader than just the killing of Lincoln. It included plans to assassinate Vice President Andrew Johnson and Secretary of State William H. Seward. However, these efforts failed—Johnson’s would-be assassin lost his nerve, and Seward, though badly injured, survived an attack. Booth himself was pursued by Union soldiers and was killed on April 26, 1865, after being cornered in a Virginia barn. Several of his co-conspirators were captured, tried, and executed. The assassination conspiracy shocked the nation and reinforced the perception that Lincoln had died a martyr for the Union cause.

Lincoln’s death had profound implications for the Reconstruction period that followed the Civil War. His approach to Reconstruction had been one of leniency and reconciliation. He advocated for a swift restoration of the Southern states to the Union with minimal retribution, provided they accepted the abolition of slavery. His “Ten Percent Plan” proposed that a Southern state could be readmitted into the Union once ten percent of its voters swore an oath of loyalty to the Union. Lincoln’s plan also aimed to extend limited voting rights to African Americans, particularly those who were literate or had served in the Union army.

However, with Lincoln’s death, the direction of Reconstruction shifted. His successor, Andrew Johnson, initially followed Lincoln’s moderate approach but quickly found himself at odds with the Radical Republicans in Congress. These lawmakers sought to impose harsher terms on the South and to ensure that African Americans gained full civil rights, including the right to vote. The conflict between Johnson and Congress led to a bitter political struggle, culminating in Johnson’s impeachment in 1868. Although Johnson was acquitted by a single vote, his presidency was largely ineffective, and the Radical Republicans took control of Reconstruction.

The Radical Republicans’ vision for Reconstruction was far more punitive than Lincoln’s. They passed the Reconstruction Acts, which divided the South into military districts and required Southern states to ratify the 14th Amendment, which granted citizenship and equal protection under the law to all persons born or naturalized in the United States, including former slaves. The 15th Amendment, passed in 1870, further extended voting rights to African American men. However, the Radical Republicans’ policies, while ambitious, faced fierce resistance in the South and eventually led to the end of Reconstruction in 1877. The withdrawal of federal troops from the South allowed the rise of Jim Crow laws, which disenfranchised African Americans and established a system of racial segregation that would persist for nearly a century.

Lincoln’s legacy is vast and multifaceted. He is remembered as the president who preserved the Union, ended slavery, and defined the moral purpose of the American experiment in democracy. His Emancipation Proclamation, while limited in its immediate effect, set the stage for the abolition of slavery and fundamentally altered the character of the nation. The 13th Amendment, which Lincoln championed, ensured that slavery would be permanently abolished. Together with the 14th and 15th Amendments, these changes, often referred to as the Reconstruction Amendments, laid the groundwork for future civil rights advancements.

Beyond his role in ending slavery, Lincoln is also celebrated for his eloquence and his ability to articulate the ideals of freedom, equality, and democracy. His speeches, particularly the Gettysburg Address and his second inaugural address, are considered among the finest in American history. In the Gettysburg Address, delivered during the dedication of the Soldiers’ National Cemetery in November 1863, Lincoln redefined the Civil War as a struggle not just for the Union but for the principle of human equality. His famous words, “government of the people, by the people, for the people,” have come to symbolize the democratic aspirations of the United States.

In his second inaugural address, delivered in March 1865, Lincoln struck a tone of reconciliation and humility. Acknowledging the deep divisions that had led to the war, he called for “malice toward none” and “charity for all” in the effort to heal the nation. This speech, which came just weeks before his assassination, encapsulated Lincoln’s vision for post-war America—a vision of forgiveness, unity, and a commitment to justice for all.

Lincoln’s assassination left many of his aspirations unfulfilled, but his legacy has endured and grown over time. He has become an iconic figure in American history, often ranked among the greatest U.S. presidents. His image and name are invoked in discussions about freedom, equality, and the responsibilities of leadership. Monuments such as the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., and his preserved home in Springfield, Illinois, stand as lasting tributes to his life and legacy. The Lincoln Memorial, in particular, has become a symbol of the nation’s commitment to civil rights, serving as the backdrop for significant events like Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech in 1963.

Lincoln’s legacy also includes his influence on the Republican Party, which he helped shape into a force for Union preservation and, eventually, civil rights. While the party’s platform and constituency have shifted over time, Lincoln’s image as the “Great Emancipator” remains central to its historical identity.

The broader impact of Lincoln’s presidency extends beyond the United States. He is often studied and admired worldwide as a model of democratic leadership. His commitment to principles, even in the face of enormous pressure and conflict, serves as an example of moral courage. In times of crisis, leaders across the globe have looked to Lincoln’s example of perseverance, integrity, and dedication to the common good.