Beneath the quiet grounds of the Nescot College Former Animal Husbandry Center in Ewell, Surrey, an ancient mystery lay buried for nearly two millennia. It wasn’t gold or jewels that captivated the archaeologists who arrived in 2015 to excavate the site, but rather bones—thousands of them. In what was once a Roman quarry pit, they uncovered one of the most enigmatic and concentrated deposits of dog remains in Roman Britain. The story that emerged from those bones, thanks to the meticulous work of Dr. Ellen Green, is one that challenges our understanding of ancient ritual, Roman attitudes toward animals, and the spiritual landscape of Britannia under Roman rule.

The pit itself was not an ordinary refuse dump. Dug into the earth as a 4-meter-deep oval shaft, the site had once served a quarrying function. But in the late first and early second centuries CE, it took on a profoundly different role. Within its dark confines accumulated a remarkable ritual assemblage—10,747 individual animal bones, over half of which belonged to dogs. This shaft, used for a relatively brief time, came to hold the largest known single collection of dog remains from Roman Britain. It demanded an explanation.

In the Roman world, dogs were far more than just pets or working animals. They hunted, herded, guarded, and comforted, serving practical and emotional roles alike. Yet, as Dr. Green emphasizes, they also inhabited a world steeped in symbolism and sacred association. Within Roman mythology and religious thought, dogs occupied a complex and often contradictory space. They were guardians of the underworld, emissaries between the worlds of the living and the dead. Associated with deities like Pluto and Hecate, they often appeared in contexts of death, fertility, healing, and even protection. Such connections spanned centuries and empires, threading through the rituals of both Greco-Roman polytheism and older, local Iron Age spiritual traditions.

It is precisely this blend of meanings that makes the interpretation of the Nescot shaft so challenging. Across most Roman-British archaeological sites, dog remains are relatively sparse—just 2% to 4% of faunal collections. At Nescot, that number exploded. Of the bones recovered, 5,436 came from dogs, representing a minimum of 140 individuals. That’s not an accident or coincidence. Something highly intentional was happening here, but the reason remains elusive.

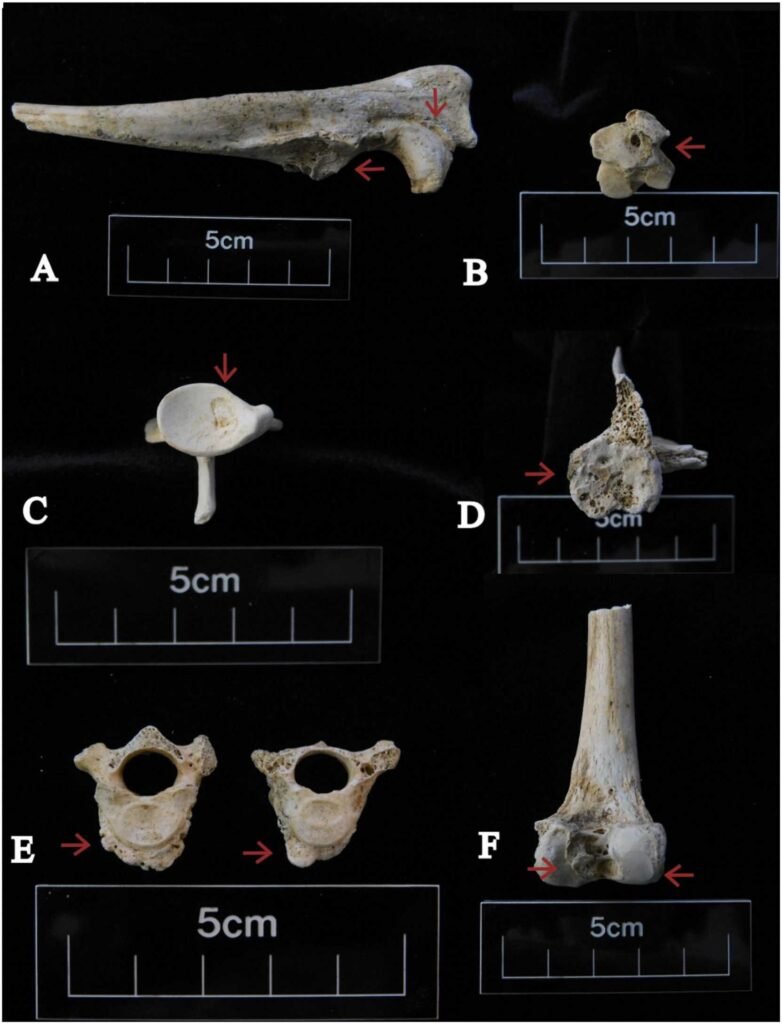

Dr. Green’s study, published in the International Journal of Paleopathology, took a deep dive into this assemblage. She catalogued the ages, sizes, and health of the animals, and compared them to findings from other sites like the Springhead sanctuary and settlement. The results painted a picture of selection, care, and ritual intent. Most of the dogs were small, with many showing signs of chondrodysplasia, a condition that results in disproportionately short limbs. These were animals akin to modern corgis or Maltese—far from the rugged hunting hounds one might expect. Their bones bore few signs of trauma or disease. When pathology was present, it was often linked to age-related conditions like spondylosis deformans or ossified costal cartilage—markers of animals who had lived relatively long lives.

Such signs hint at a form of care that contradicts the idea of these dogs being disposable. They were not butchered, skinned, or discarded. There were no cut marks to suggest their end was driven by hunger or craft. Instead, their bodies were laid to rest in a pit already rich with ritual significance. And they were not alone. The shaft also yielded coins, pottery, gaming tokens, and even human remains—items often linked with offerings or funerary contexts.

Why would such animals be sacrificed? Dr. Green believes the answer lies in Roman cultural codes surrounding ritual and divine offerings. “I think that, most likely, they were selected based on specific cultural criteria,” she explains. The Romans had detailed expectations for the types of animals suitable for various deities and ceremonies. Color, sex, age—all could be factors. It’s plausible that the small, often elderly dogs at Nescot were chosen for very specific spiritual functions.

Moreover, while inbreeding might account for some of the physical traits seen among the remains—such as scapular lesions and other signs of hereditary weakness—the overall diversity in size and form suggests these dogs did not come from a single, isolated population. This adds to the mystery: if they weren’t raised together solely for ritual, then they must have been gathered from various sources for a particular purpose.

To understand the Nescot shaft fully, one must consider the broader context of animal sacrifice and ritual in Roman Britain. The Romans absorbed many local traditions from the people they conquered, and Britannia was no exception. While Roman records often documented their own rites in detail, the native Iron Age peoples left no written accounts. Yet their ritual sites frequently include dog burials, suggesting that even before Roman influence, canines held sacred status. The Romans may have absorbed or adapted these practices, fusing them with their own rich tapestry of myth and ritual.

Interestingly, a comparison with more urban sites like the Springhead settlement reveals another dimension. Dogs buried in such locations often bore signs of being strays or animals of lesser health. By contrast, places like Nescot, which appears to have served a more explicitly ritualistic function, show a higher prevalence of healthy, well-cared-for animals. This points to a kind of ritual hierarchy, where the condition and type of animal reflected the sanctity of the rite or the perceived demands of the deity being honored.

As the use of the shaft progressed through three distinct phases, its function shifted. The first two phases were marked by intense ritual deposition—hundreds of animals, tokens, and relics. But by the third phase, something had changed. The volume of remains dropped dramatically. The few bones found bore cut marks and chop marks, fresh breaks that spoke of marrow extraction and butchery. These were not offerings—they were waste. It seems that, for reasons unknown, the shaft lost its sacred status. Perhaps the religious practices it once supported fell out of favor, or the community that once revered the site moved on. By the early second century, the pit was abandoned entirely.

In a sense, the story of the Nescot shaft is not just about dogs or rituals. It’s a story about cultural change, the blending of Roman and British spiritual life, and the way communities assign meaning to the creatures around them. The dogs buried in that shaft weren’t just animals—they were symbols, participants in rites that have been lost to time. Their bones whisper of an age when the boundary between the natural and supernatural was thinner, when a small, aging dog could serve as a bridge between worlds.

Archaeology often deals in fragments—a pottery shard here, a bone there. Rarely does it uncover a cache as dense and evocative as that of Nescot. And while the exact rites conducted there may never be fully understood, the evidence offers a compelling glimpse into a deeply symbolic world. Through Dr. Green’s study, these ancient dogs have found a new voice, one that speaks across centuries to remind us that ritual is not always logical, but it is deeply human. The shaft may have been filled with silence for nearly 2,000 years, but its secrets are only now beginning to speak.

More information: Ellen Green, The pathology of sacrifice: Dogs from an early Roman ‘ritual’ shaft in southern England, International Journal of Paleopathology (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.ijpp.2025.02.005