More than three thousand years ago, the world was alive with the hum of civilization. Great kingdoms and empires rose around the shimmering waters of the eastern Mediterranean and Near East. In Egypt, pharaohs ruled from their monumental palaces, their armies marching under banners of gold. To the north, the Hittite Empire stretched across Anatolia, commanding trade routes and iron mines. Across the Aegean, the Mycenaean Greeks built citadels of stone and filled their tombs with treasure. In Mesopotamia, the Babylonians wrote in cuneiform on clay tablets, recording laws, trade, and poetry.

This was the Bronze Age — an era that began around 3300 BCE and saw humanity master metal, trade, and writing. Bronze, the alloy of copper and tin, was the superweapon of its day — harder and sharper than stone, capable of forging swords, plowshares, and sculptures of gods. The Bronze Age connected worlds through trade networks that stretched from the British Isles to the Indus Valley. Gold, spices, lapis lazuli, and olive oil crossed mountains and seas. Kings corresponded through letters sealed in clay and sent by emissaries who carried gifts and treaties.

The civilizations of the Late Bronze Age were the first to form a truly international world — a web of economies, alliances, and cultural exchange that bound Egypt, the Hittites, the Mycenaeans, the Canaanites, the Assyrians, and the Minoans together. They spoke different languages and worshiped different gods, but they shared a common system of trade, diplomacy, and warfare.

Then, around 1200 BCE, that world began to unravel.

The Great Collapse Begins

In the span of just a few decades, the great Bronze Age civilizations of the eastern Mediterranean fell into chaos. Palaces burned, cities were abandoned, and writing systems vanished. Trade routes that had endured for centuries crumbled into silence. From Greece to Mesopotamia, societies that had once seemed invincible disappeared, leaving behind ruins and unanswered questions.

The collapse of the Bronze Age around 1200 BCE marks one of the most mysterious and catastrophic events in human history. Archaeologists still struggle to explain why so many powerful civilizations — the Mycenaeans, Minoans, Hittites, Canaanites, and others — collapsed almost simultaneously. Theories abound: invasions, earthquakes, droughts, famine, rebellion, and systemic collapse. Most likely, it was not a single cause but a convergence — a perfect storm of disasters that struck a fragile, interconnected world.

At the heart of the catastrophe was the fragility of the Bronze Age system itself. Its complexity, once its greatest strength, became its fatal weakness.

The World Before the Fall

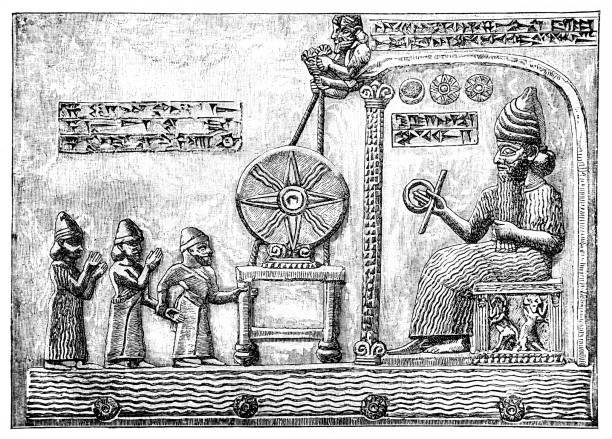

Before the collapse, the Late Bronze Age world was a marvel of internationalism. The so-called “Great Powers Club” — Egypt, the Hittite Empire, Babylon, Assyria, and Mycenaean Greece — maintained relations through diplomacy, trade, and even royal marriages. The Amarna Letters, discovered in Egypt, reveal kings addressing each other as “brother,” exchanging gifts of gold, ivory, and horses.

This system depended on stability and long-distance trade. Bronze required both copper and tin — two metals rarely found in the same region. The collapse of trade meant the end of bronze production, and with it, the tools, weapons, and symbols of power that underpinned these civilizations.

It was an age of splendor and dependence. Palaces managed vast bureaucracies. Scribes recorded harvests and treaties. Armies relied on chariots and archers. Farmers supplied grain to temples and courts. But beneath the surface of prosperity, tension brewed. Populations grew, climate patterns shifted, and local resources were stretched thin. The system that bound kingdoms together was efficient — but brittle.

Fire and Ruin

Between 1220 and 1150 BCE, the ancient world ignited. Archaeological evidence reveals a chain reaction of destruction. Mycenaean palaces — Tiryns, Mycenae, and Pylos — were reduced to ashes. The Hittite capital, Hattusa, was burned and abandoned. Cities along the Levantine coast — Ugarit, Byblos, and Ashkelon — were razed. Even mighty Egypt was invaded and barely survived.

From the Aegean to the Near East, writing vanished. The Mycenaean Linear B script disappeared forever, and the Hittite cuneiform tablets ceased. The great networks of correspondence that once linked kings and merchants fell silent.

In the ruins of Ugarit, archaeologists found letters from a desperate king begging for help: “My father, the enemy ships are approaching! The cities are burning! My armies are gone!” The plea was never answered. The letter was found baked in clay — not by design, but by the fire that destroyed the city.

The destruction was not uniform. Some cities survived, some regions recovered quickly. But the interconnected system of trade and political order that had defined the Bronze Age was gone. The Mediterranean plunged into a centuries-long period of decline — a true dark age.

The Sea Peoples and the Storm from the West

Among the most famous — and feared — agents of the collapse were the so-called Sea Peoples. These mysterious raiders appeared suddenly in Egyptian records, described as a confederation of tribes from the sea who swept through the eastern Mediterranean, burning and plundering coastal cities.

The Egyptians, under Pharaoh Ramesses III, recorded fierce battles against them around 1177 BCE. Reliefs at his mortuary temple in Medinet Habu depict naval battles and scenes of captured warriors. Ramesses claimed victory, but even Egypt, the most enduring of the Bronze Age powers, was gravely weakened.

The identity of the Sea Peoples remains one of archaeology’s enduring mysteries. Some scholars believe they were displaced populations from the Aegean or Anatolia — perhaps refugees fleeing famine, earthquakes, or war. Others suggest they were mercenaries, pirates, or rebels against collapsing states. What is certain is that they were both symptom and cause — opportunists born from the chaos, and agents who deepened it.

The migrations and invasions triggered by these movements reshaped the ancient world’s demographics. Coastal cities vanished, and new cultures emerged from the wreckage. The Philistines, for example, likely descended from some of these migrating groups, settling along the coast of Canaan and giving their name to Palestine.

Natural Catastrophes and Climatic Chaos

For decades, scholars sought a single dramatic explanation for the Bronze Age Collapse. In recent years, science has provided evidence that nature itself played a major role.

Studies of sediment cores, pollen samples, and ancient tree rings suggest that a prolonged drought struck the eastern Mediterranean around 1200 BCE. This “megadrought” may have lasted decades, devastating agriculture and triggering famine. In an economy dependent on grain surpluses and trade, crop failure would have been catastrophic.

Texts from Ugarit and Hattusa speak of hunger, migration, and desperation. “There is famine in your house,” one letter reads, “we shall all die of hunger.” As harvests failed, societies dependent on central authority faltered. Starving populations turned against their rulers, and kingdoms that once projected power found themselves besieged by rebellion.

Earthquakes, too, played their part. The eastern Mediterranean lies on active fault lines, and a series of quakes around 1200 BCE destroyed several key cities, including Mycenae and Troy. Some archaeologists refer to this period as the “earthquake storm.” Combined with war and famine, these disasters formed a feedback loop of collapse.

The Fall of the Hittites

Perhaps no empire illustrates the Bronze Age Collapse more vividly than the Hittites. At their height, they were one of the great powers of the ancient world, controlling much of Anatolia and northern Syria. Their capital, Hattusa, was a monumental city of stone walls, temples, and archives.

Then, around 1200 BCE, the Hittite Empire vanished almost overnight. Its capital was burned, its provinces fragmented, and its people scattered. The causes remain debated — internal rebellion, famine, invasion, or a combination of all three. Whatever the truth, the Hittites disappeared from history for nearly three thousand years, remembered only in the Bible until archaeologists rediscovered their ruins in the 19th century.

Their fall was part of a domino effect that rippled through the region. With the Hittites gone, trade routes through Anatolia collapsed. Neighboring states like Ugarit lost their connections and fell soon after. The web of interdependence that had sustained the Bronze Age was torn apart thread by thread.

The Decline of Mycenaean Greece

Across the Aegean, the Mycenaean civilization — remembered later in Greek myth as the world of Agamemnon and Achilles — also met its end. Archaeological evidence shows that between 1200 and 1100 BCE, nearly every major Mycenaean palace was destroyed. Mycenae, Pylos, Thebes, and Tiryns all fell within decades.

The reasons for the collapse in Greece mirror those elsewhere: climate change, invasions, and social upheaval. But internal strife may have played a decisive role. The Mycenaean palaces were centers of bureaucracy and hierarchy, reliant on the labor of peasants and slaves. When crops failed or trade faltered, these rigid systems could not adapt.

After the palaces burned, Greek society fragmented into small, isolated communities. Writing disappeared, and monumental architecture ceased. This period — known as the Greek Dark Age — would last nearly four hundred years. Yet from its ashes, a new world would eventually rise: the world of Homer, city-states, and classical Greece.

Egypt’s Narrow Escape

Of all the great powers of the Late Bronze Age, Egypt alone survived the collapse with its identity intact — but only barely.

During the reigns of Pharaohs Merneptah and Ramesses III, Egypt faced invasions from Libyans, Nubians, and the Sea Peoples. Ramesses’ inscriptions boast of victory, but his victories were pyrrhic. The empire’s economy was drained, its borders weakened, and its trade network shattered.

After 1100 BCE, Egypt retreated inward. It lost its Syrian and Palestinian territories and entered a slow decline. The age of the great pharaohs was over. The once-mighty kingdom that had built the pyramids and ruled from the Nile to the Euphrates now struggled to feed itself.

The Silent Centuries

What followed the collapse was a silence that lasted centuries. Across the eastern Mediterranean, literacy disappeared, cities shrank, and population levels plummeted. Trade withered, and artistic and architectural achievements regressed.

For historians, this period — roughly 1100 to 800 BCE — marks the world’s first true “Dark Age.” It was not dark in the sense of total ignorance, but in the loss of light — of record, memory, and connection. Generations passed without writing, and knowledge once preserved in archives and schools vanished.

Yet even in the darkness, life continued. Small communities persisted in the ruins of old cities. Farmers tilled fields once owned by kings. Oral traditions kept the memory of the past alive. In Greece, stories of the Mycenaean age evolved into epic poetry — tales of heroes and gods, of Troy and Olympus. These myths were the last flickering embers of a vanished world.

The Rise from the Ashes

By around 800 BCE, the Mediterranean world began to awaken. New technologies and societies emerged from the ruins of the Bronze Age. Chief among them was the widespread use of iron. Unlike bronze, which required rare tin, iron was abundant and accessible. Though harder to smelt, once mastered it transformed warfare, agriculture, and trade.

The Iron Age brought with it new political orders. In Greece, city-states like Athens and Sparta began to form. In the Levant, the Phoenicians rebuilt their coastal cities and pioneered seafaring trade across the Mediterranean, spreading the alphabet — a simple yet revolutionary system of writing that replaced the complex scripts of the Bronze Age.

Assyria rose from the shadows of Mesopotamia to build one of history’s first great empires. Israel and Judah emerged in the highlands of Canaan. The world was remade, not in the image of the Bronze Age palaces, but through smaller, more adaptable systems that valued resilience over grandeur.

The collapse, though catastrophic, was not the end of civilization. It was a transformation — the death of one world and the birth of another.

The Lessons of Collapse

The story of the Bronze Age Collapse is not merely an ancient mystery — it is a warning written in the ruins of history. The civilizations that fell were not primitive; they were complex, globalized, and technologically advanced for their time. They depended on trade, specialization, and political hierarchy. Their collapse reminds us how fragile such systems can be when confronted by environmental stress, resource scarcity, and interdependence.

When climate shifted and trade faltered, when armies failed and populations fled, the intricate web that sustained them came apart. Complexity became vulnerability.

Modern scholars, from archaeologists to climatologists, see echoes of the Bronze Age Collapse in our own world. Globalization, climate change, migration crises, and political instability mirror some of the same forces that unmade those ancient kingdoms. The Bronze Age teaches that no civilization, however advanced, is immune to systemic failure.

Remembering the Forgotten Age

Today, the remnants of the Bronze Age still stand — silent witnesses to a vanished era. The citadel walls of Mycenae, the ruins of Ugarit, the lion gates of Hattusa — all speak of a world that once glimmered with power and knowledge.

For centuries, historians could only guess at what happened between the fall of Troy and the rise of classical Greece. But archaeology, linguistics, and climate science have begun to piece the story together. Each shard of pottery, each charred palace floor, tells part of the tale of how civilization itself nearly ended — and began anew.

The Bronze Age Collapse is not just an event in the distant past. It is a mirror reflecting the cycles of human achievement and fragility. From its ashes rose new languages, technologies, and ideas that shaped the future. Without that fall, there might have been no Homer, no Greece, no Rome — and perhaps no modern world as we know it.

The Darkness Before the Dawn

In the end, the collapse of the Bronze Age was both tragedy and rebirth. It was the first great unmaking of human civilization — a descent into chaos that paved the way for renewal. The darkness that followed was not the end of progress, but the pause before a new beginning.

The people who survived — farmers, traders, poets, and warriors — carried fragments of the old world into the new. Their resilience, their ability to adapt and rebuild, ensured that human culture did not vanish with the fall of palaces.

The Bronze Age Collapse stands as a monument not only to what can be lost, but to what can be learned. It reminds us that civilization is a fragile flame — one that must be tended, renewed, and protected against the winds of change.

From the ashes of bronze rose the iron will of humanity — tempered, enduring, and ready to forge the next chapter of history.