History is often told as a grand narrative—a linear tale of progress, discovery, and the rise of great empires. Names like Rome, Egypt, and China dominate textbooks and documentaries, celebrated as cradles of civilization. But beneath the familiar story lies a haunting truth: entire civilizations, some ancient and complex, vanished without a trace. Not just conquered or assimilated—erased. Their languages silenced, their cities buried, their achievements forgotten by time itself.

What happened to these lost worlds? Were they wiped out by war, swallowed by nature, or slowly forgotten through neglect and decay? And why, in some cases, did the victors go to such lengths to ensure their memory was scrubbed clean? The story of how civilizations are erased from history is not only about tragedy; it is also about the fragility of memory, the power of narrative, and our endless quest to rediscover what was lost.

The Fragile Nature of Legacy

To understand how civilizations disappear, we must first understand what keeps them alive in our collective memory. A civilization is more than its buildings or borders—it is the culture, the language, the stories, and the knowledge passed down through generations. This intangible heritage is fragile. When a society falls, especially abruptly, its memory can be lost within a few generations unless it is preserved in writing, adopted by others, or remembered in oral tradition.

But even written records are vulnerable. Texts can be burned. Languages can die. Libraries can be looted. And when these things happen—when knowledge is deliberately destroyed or simply allowed to vanish—we are left with ghosts. Archaeologists may find ruins, fragments, bones. But the soul of a civilization—the meaning behind its art, the subtleties of its politics, the identities of its heroes—can vanish forever.

The Victims of Time: Civilizations Buried by Catastrophe

Throughout history, natural disasters have played a significant role in the erasure of civilizations. Take the Minoans, for instance. Flourishing on the island of Crete around 2000 BCE, the Minoans were master sailors, traders, and artists. Their palace at Knossos was a marvel of ancient architecture, complete with advanced plumbing and vibrant frescoes. But around 1600 BCE, a massive volcanic eruption on the nearby island of Thera (modern-day Santorini) triggered a tsunami that devastated Minoan ports and infrastructure.

Though they tried to recover, the Minoans were weakened, making them vulnerable to Mycenaean conquest. In time, their writing system—Linear A—remained undeciphered, and their legacy faded. Without decipherable texts to tell their story, the Minoans teetered on the edge of complete historical erasure. They were rediscovered only in the 20th century by archaeologist Arthur Evans.

Another haunting example is the city of Akrotiri, also buried by the Thera eruption. Its perfectly preserved frescoes and architecture tell us it was once a thriving urban center. But until its excavation in the late 20th century, no one even knew it had existed. Time had not just buried it—it had silenced it.

Erased by Conquest: The Destruction of Identity

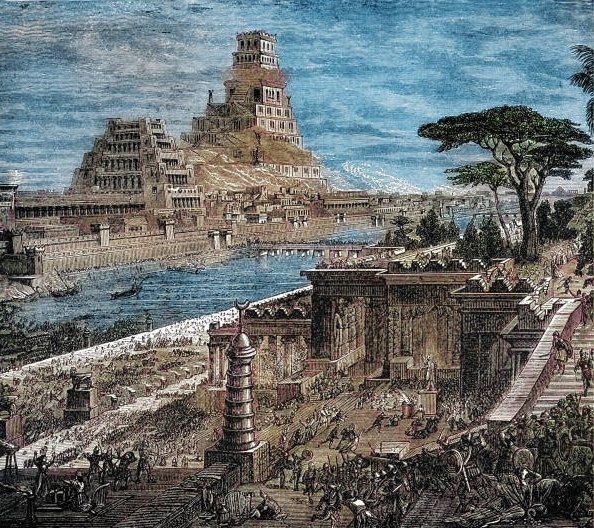

War has always been a catalyst for erasure. Conquerors often sought not just to defeat, but to obliterate the identities of those they conquered. This process, often called “damnatio memoriae,” or the condemnation of memory, was practiced by the Romans to wipe disgraced figures from public records. Statues were destroyed, names were scratched from inscriptions, and legacies were rewritten.

But this was not just a Roman phenomenon. The Assyrians, notorious for their brutal military campaigns, often razed the cities of rival kingdoms, slaughtered their elites, and deported the surviving populations. These tactics not only conquered a people but dismantled their culture from within.

One of the most chilling examples comes from the Americas. The Spanish conquest of the Aztec and Inca empires was not only physical—it was intellectual and spiritual. Indigenous books (codices) were burned en masse by Spanish priests. In 1562, Bishop Diego de Landa ordered the burning of thousands of Mayan texts, declaring them “superstition and lies of the devil.” These books contained astronomical records, mythology, and centuries of accumulated wisdom. Today, only four authenticated pre-Columbian Maya codices survive.

With their destruction, entire centuries of knowledge vanished. Without their own records, these civilizations came to be known only through the eyes of their conquerors—a biased lens that often painted them as savage, backward, or primitive.

The Curse of Oral Cultures

Not all civilizations kept written records. Many relied on oral tradition—songs, stories, chants, and ceremonies—to pass down knowledge. For these cultures, colonialism was doubly devastating. When elders were killed or displaced, when languages were suppressed, when generations were severed from tradition, entire knowledge systems evaporated.

In Africa, the continent once home to great empires like Mali, Songhai, and Great Zimbabwe, colonial narratives long depicted it as a place without history. European colonizers dismissed oral traditions as unreliable, ignoring rich intellectual traditions preserved by griots (oral historians) and poets. It wasn’t until the 20th century that scholars began to uncover the complexity and sophistication of African civilizations through archaeology and the revival of oral accounts.

But the damage had been done. Great libraries, such as the one in Timbuktu, had been plundered. Oral lineages were broken. And even today, many African civilizations remain marginalized in historical discourse, their contributions minimized or ignored.

Religious Zeal and the Cleansing of the Past

Religion, too, has been a powerful force in the erasure of civilizations. The early Christian Church, in its quest to establish orthodoxy, labeled many pre-Christian cultures as pagan, heretical, or demonic. Temples were razed. Sacred groves were cut down. Statues were defaced.

The Library of Alexandria—a beacon of knowledge in the ancient world—is perhaps the most famous casualty of such zeal. Though its destruction was the result of multiple events over centuries, religious riots and Christian purges in the late Roman Empire played a significant role in its decline. Countless texts from Greece, Egypt, Babylon, and India were lost forever, cutting us off from a vast repository of human thought.

Later, during the Islamic expansion, many Persian and Indian texts were similarly lost, despite the preservation efforts of scholars during the Islamic Golden Age. In medieval Europe, countless Druidic and Nordic traditions were erased by the spread of Christianity. What we know of these cultures is fragmentary, filtered through Christian chroniclers who often misunderstood or misrepresented the beliefs of the people they conquered.

The Political Power of Forgetting

Erasing a civilization can be as much a political act as a physical one. Regimes have long used the suppression of history to control narratives. Stalin’s Soviet Union famously altered photographs to remove political enemies from history. But even earlier, rulers rewrote history to suit their needs.

In ancient Egypt, Pharaoh Akhenaten introduced a monotheistic religion, worshipping Aten, the sun disk. After his death, his successors—most notably Tutankhamun and Horemheb—systematically destroyed his statues, defaced his monuments, and tried to obliterate his name from records. For centuries, his memory was lost, and he became known as the “heretic king.”

Similarly, the Hittites, a powerful Bronze Age empire that rivaled Egypt, disappeared so thoroughly after their collapse that their existence wasn’t confirmed until the 20th century. For centuries, they were considered a biblical myth—until archaeologists uncovered their capital, Hattusa, and a massive trove of cuneiform tablets.

The erasure of civilizations is not always accidental. Sometimes it is intentional, orchestrated by those who benefit from forgetting.

Lost Beneath the Earth: The Silence of the Unexcavated

Even in modern times, much of our planet’s history remains buried. It’s estimated that only a fraction of ancient cities have been excavated. Vast civilizations lie beneath modern cities, deserts, jungles, and oceans—awaiting discovery.

In the Indus Valley, the cities of Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa were only unearthed in the 1920s, revealing an urban culture as advanced as those in Mesopotamia and Egypt. Yet we still can’t read their script. We don’t know what they called themselves. Their religion, political system, and even their downfall remain largely speculative.

In the Amazon rainforest, satellite imagery has revealed geometric earthworks—evidence of sophisticated societies that once thrived in regions long assumed to be wild and uninhabited. These “lost cities” were likely wiped out by disease after European contact, their populations decimated before they ever met a conquistador.

Every year, new discoveries challenge our assumptions. Civilizations thought to be minor or mythical are proven real. Others, long known through ruins, are still being interpreted. And still others remain silent, their stories entombed in stone or soil.

The Digital Age and the Race to Recover

In today’s world, technology is helping us rediscover what was lost. Satellite imaging, LIDAR scanning, and advanced dating techniques are revealing ancient cities, temples, and trade routes once thought to be mythical. Digital archaeology is enabling the reconstruction of destroyed artifacts, like those smashed by ISIS in Palmyra.

But even as we race to recover the past, new threats loom. Climate change, urbanization, looting, and warfare continue to endanger what remains. Entire archaeological sites are being destroyed before they can be studied. Languages die out every year. And with each loss, the historical record grows thinner.

That is why the preservation of history is no longer just an academic concern—it is a global imperative.

Conclusion: Memory as Resistance

The erasure of civilizations reminds us of the fragile nature of human memory. It forces us to ask difficult questions: Who controls history? Who decides what is remembered or forgotten? And what treasures of knowledge have we already lost?

But it also inspires awe. Against all odds, some fragments survive. A shard of pottery. A buried temple. A language reborn. These fragments are not just archaeological data—they are acts of resistance. Every rediscovered city, every deciphered script, every revived tradition reclaims space in the narrative of humanity.

We may never fully recover what was lost. But by seeking, remembering, and honoring the vanished, we defy the forces that tried to erase them. In doing so, we enrich our own understanding—not just of the past, but of who we are today.