Every human being carries within their body a story written in blood, bone, and DNA—a story that stretches back millions of years. It is the story of survival, chance, and transformation, of creatures who stood on trembling legs and dared to look at the sky. Human evolution is not just a scientific chronicle—it is a saga of resilience and imagination, filled with shocking twists that shaped our species into what we are today.

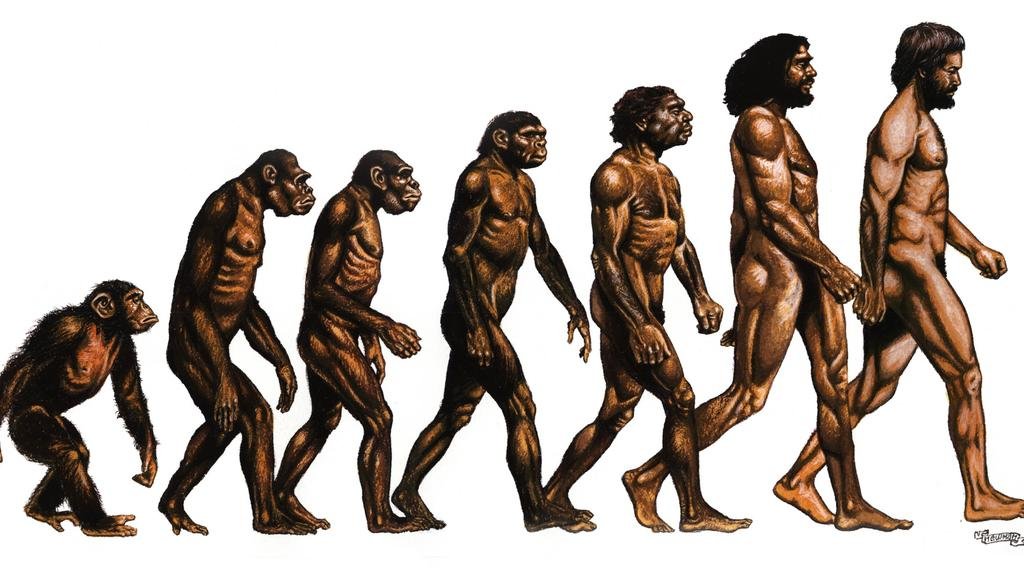

When we look into the mirror, we see not only ourselves but the echoes of countless ancestors who walked the Earth long before history began. We are the product of endless experiments by nature—each success and failure etched into our genome. From ape-like creatures wandering the forests of Africa to the builders of civilizations and dreamers of stars, our journey has been one of continuous change.

But this evolution was not a straight path. It was a labyrinth, full of dead ends, unexpected mutations, climatic catastrophes, and improbable miracles. To understand who we are, we must travel back through the shadows of deep time, where every discovery rewrites our place in the grand tapestry of life.

The Dawn Before Humanity

Long before humans appeared, Earth was home to a diverse family of primates. About 65 million years ago, when the age of the dinosaurs ended in fiery destruction, small, clever mammals began to rise. Among them were the ancestors of primates—creatures with grasping hands, forward-facing eyes, and growing intelligence.

Over tens of millions of years, these early primates diversified. Some lived in trees, leaping from branch to branch. Others descended to the ground, adapting to new environments. Evolution rewarded those who could adapt, learn, and cooperate. The line that would eventually lead to humans was just one among many—an unremarkable branch at first glance, but destined for greatness.

By around 7 million years ago, a group of African apes began to change. Climate shifts were turning lush forests into open savannas, forcing our ancestors to adapt or perish. Those who could walk upright gained an advantage—they could see over tall grass, carry food and tools, and travel greater distances.

This was the birth of bipedalism, the defining step that set our lineage apart. The world had seen many creatures walk on two legs, but for the first time, intelligence and upright posture combined to create something unprecedented: the foundation of humanity.

The First Step Into Humanity

Among the earliest known human ancestors is Sahelanthropus tchadensis, who lived about seven million years ago in what is now Chad. With both ape-like and human-like traits, it represents a bridge between two worlds—the wild forests of our primate past and the open plains of our future.

Then came Australopithecus afarensis, famously represented by the fossil “Lucy,” discovered in Ethiopia. She lived about 3.2 million years ago, walked upright, yet still climbed trees with ease. Lucy’s skeleton tells a story of transition—a species balancing between past and future, adapting to a new way of life.

Walking upright was a revolutionary act. It freed our hands for other tasks—carrying tools, gathering food, and eventually creating art. This simple shift in posture altered everything: our diet, our anatomy, our brain, and even the structure of our societies. It was not just a physical change but a cognitive one.

As our ancestors walked, they began to think differently. Their world expanded, both physically and mentally. They could see farther, move faster, and imagine beyond the next meal. Evolution was slowly sculpting creatures capable of dreaming.

The Power of Fire and Stone

Around 2.5 million years ago, a new species emerged: Homo habilis—literally “handy man.” They were the first known toolmakers, crafting sharp-edged stones to cut meat, scrape hides, and shape wood. With tools came control over the environment—a defining moment in our evolutionary ascent.

Fire, too, became a force of transformation. Although early humans did not yet master it, they learned to take advantage of natural flames left by lightning or volcanic activity. Eventually, Homo erectus—our ancestor who appeared around 1.9 million years ago—became the true keeper of fire.

Fire was more than warmth and protection. It was a source of light in the darkness, a social center around which language and culture evolved. Cooking food broke down tough fibers, making nutrients easier to digest and fueling brain growth. The crackling fire was the first spark of civilization.

Homo erectus was also the first great traveler. They spread out of Africa into Asia and Europe, adapting to countless environments. For nearly two million years, they ruled as the most successful hominins on Earth. Their legacy is written in stone tools scattered from Kenya to Indonesia—a trail of endurance across continents.

The Brain That Changed Everything

The evolution of the human brain is one of nature’s most astonishing feats. Compared to our ape cousins, early humans had brains that were small, roughly 400–500 cubic centimeters. But as our ancestors evolved, their brains began to grow—first to 800 cc in Homo erectus, then to over 1,300 cc in modern Homo sapiens.

What drove this expansion? The answer lies in survival, cooperation, and imagination. Bigger brains allowed for better communication, planning, and emotional intelligence. Those who could form alliances, predict danger, and share knowledge had a greater chance of passing on their genes.

Language was perhaps the most revolutionary product of this growth. No other species on Earth can convey abstract ideas, tell stories, or plan generations ahead. Through language, humans could share not just experiences, but dreams.

Our brains also gave birth to something uniquely human—art, ritual, and self-awareness. The ability to reflect on our existence—to know that we will die—set us apart forever. Evolution had created not just a clever animal, but a conscious being.

The Age of Wanderers

Roughly 300,000 years ago, Homo sapiens—our own species—appeared in Africa. The earliest fossils, found in Morocco, reveal faces that look strikingly modern. These were not brutish cave dwellers, but humans with minds capable of art, compassion, and complexity.

From Africa, we began to wander. Between 60,000 and 70,000 years ago, small bands of humans crossed the Sinai Peninsula and spread into the Middle East, Asia, and beyond. Some reached Australia by 50,000 years ago, others Europe soon after, and eventually the Americas.

This global journey was not a conquest, but a migration of survival and curiosity. As humans moved into new lands, they adapted to freezing tundras, arid deserts, and dense jungles. They hunted mammoths, fished in rivers, and learned to build shelters against the cold.

Every continent bears traces of this journey. Ancient DNA reveals that all modern humans share a common African origin—a truth that unites us beneath our superficial differences. We are, all of us, one family that once walked out of Africa and never stopped exploring.

The Forgotten Cousins

Human evolution is not a single line leading neatly to us—it is a tangled bush of branches. For most of history, we shared the world with other human species. Some we met, some we never saw, and others we merged with.

The Neanderthals, Homo neanderthalensis, were one such species. Stocky, strong, and intelligent, they thrived in Ice Age Europe for hundreds of thousands of years. They made tools, buried their dead, and perhaps even painted on cave walls.

For a long time, scientists viewed Neanderthals as inferior, primitive brutes. But new discoveries have shattered that myth. They were our equals in many ways—emotionally, socially, and technologically. The difference was not intellect, but luck and adaptability.

When modern humans arrived in Europe around 45,000 years ago, the two species coexisted—and interbred. Genetic evidence shows that nearly all non-African humans today carry between 1% and 3% Neanderthal DNA. Their blood still flows within us, a silent reminder of an ancient connection.

And Neanderthals were not the only cousins. In Asia, Denisovans lived alongside both humans and Neanderthals. Their DNA, too, survives in modern populations—especially among Melanesians and Aboriginal Australians.

The story of humanity is thus not one of purity but of blending. We are hybrids of multiple lineages, united by the shared will to survive.

The Catastrophe That Almost Erased Us

Around 74,000 years ago, disaster struck. The Toba supervolcano in Indonesia erupted with unimaginable force, blanketing the world in ash and plunging the planet into volcanic winter. It is believed that global temperatures dropped sharply, killing plants, animals, and perhaps entire human tribes.

Genetic studies suggest that humanity’s numbers may have plummeted to just a few thousand individuals. We came perilously close to extinction. Those who survived likely lived in isolated pockets in Africa, relying on innovation and cooperation to endure.

It was during this crucible of survival that human creativity blossomed. Facing desperate conditions, early humans developed new tools, built stronger social bonds, and began to express themselves through art. The very pressure of survival forged the spark of genius.

The Birth of Culture and Symbolism

As the Ice Age waned, human creativity exploded. In the caves of France and Spain, ancient artists painted magnificent scenes of bison, horses, and mammoths. In Africa, engraved shells and beads appeared, symbols of identity and beauty.

These were not mere decorations—they were expressions of thought, communication, and spirituality. Humans had begun to see the world not just as a place to survive, but as a realm of meaning.

This shift marked the birth of culture. People formed tribes, shared myths, and passed down knowledge through generations. They sang, danced, and told stories by firelight—acts that reinforced bonds and transmitted wisdom.

Our ancestors also began to bury their dead with care, suggesting belief in an afterlife. This awareness of mortality and transcendence was a profound leap. The same brain that invented tools now pondered eternity.

The Rise of Agriculture and Civilization

For hundreds of thousands of years, humans lived as hunter-gatherers—following herds, gathering fruits, and living in balance with nature. But about 12,000 years ago, something extraordinary happened. In several regions across the world, humans began to cultivate plants and domesticate animals.

This shift—the Agricultural Revolution—was one of the most transformative moments in our history. It allowed people to settle, form villages, and eventually build cities. Grains like wheat, barley, and rice became staples, while animals such as goats, cattle, and dogs became companions and laborers.

Agriculture changed everything: our diet, our society, our health, even our DNA. Populations grew, civilizations emerged, and the first complex economies developed. But it also brought inequality, war, and disease.

Evolution didn’t stop with civilization. Humans continued to adapt. Genetic changes allowed some populations to digest milk, resist malaria, or thrive in high altitudes. The story of evolution shifted from bones to behaviors, from jungles to cities.

The Brain’s Final Frontier

Human evolution did not end in the past—it continues within us. Our brains, though immensely powerful, are still evolving. Modern humans use abstract thought, logic, creativity, and emotion in ways no other species can. Yet the same brain that crafted art and philosophy also struggles with anxiety, aggression, and bias—echoes of our primal past.

Our emotions, instincts, and fears are evolutionary relics that once kept us alive. The adrenaline rush of danger, the tribal instinct to protect kin, the curiosity to explore—all are ancient gifts from ancestors who faced predators and hunger.

In our modern world, those instincts sometimes clash with our environment. We are creatures of stone-age minds living in a digital age, struggling to adapt once again.

The DNA That Connects All Life

In the 20th century, a new revolution began—not in tools or fire, but in understanding the code of life itself. The discovery of DNA revealed that all living things share a common ancestry. Humans are not separate from the rest of nature; we are its continuation.

Our genome contains about 20,000 genes—many shared with other species. We share 98.8% of our DNA with chimpanzees, our closest living relatives, and more than 60% with bananas. Evolution is a continuous thread linking every organism, from the smallest microbe to the tallest tree.

Through genetic research, we can now trace our migrations, identify ancient interbreeding, and even reconstruct the faces of our ancestors. DNA has become the ultimate storyteller of evolution.

The Turning Points That Made Us Human

If we look back at the long road of human evolution, certain moments stand out as defining: the first step on two legs, the first spark of fire, the first tool, the first word, the first painting on a cave wall. Each was a shock—a leap of imagination and survival that changed everything.

Our journey was never guaranteed. At countless points, humanity could have perished. But again and again, our ancestors adapted. They learned to cooperate, to innovate, to hope. Evolution favored not the strongest or fastest, but the most adaptable—the dreamers, the storytellers, the thinkers.

We are the sum of all their choices, accidents, and triumphs. Every heartbeat today is a continuation of that ancient rhythm that began millions of years ago in the savannas of Africa.

The Mirror of Time

To understand human evolution is to see ourselves with humility. We are not the pinnacle of creation but one branch of a vast, ongoing experiment. Our ancestors’ bones remind us that intelligence alone is not enough—survival requires balance, empathy, and respect for the planet that shaped us.

In the face of modern challenges—climate change, extinction, war—we are once again tested. Will we adapt wisely, or will we become another lost chapter in the book of life?

The same evolutionary forces that created us still govern our fate. The difference now is that we are aware—we can shape our own evolution through technology, medicine, and choice. But awareness comes with responsibility.

The Endless Journey

Human evolution is far from over. Our bodies, minds, and societies continue to change. Artificial intelligence, genetic engineering, and space exploration are opening new horizons that could lead to the next great transformation.

Perhaps future humans will merge with machines, or colonize other planets. Perhaps our descendants will evolve into beings we can scarcely imagine—creatures of intellect, empathy, or even pure consciousness.

Whatever form that future takes, one truth will remain: we are children of evolution, shaped by fire, storm, and time. Our story is written in stardust and struggle, in love and loss, in endless adaptation.

The Legacy of Becoming

Human evolution is not just a biological process—it is a narrative of becoming. From the trembling hand that first struck two stones together to the mind that now contemplates its own origins, our species has never stopped reaching.

We are the only creatures who ask, “Who am I?” and “Why am I here?”—questions born from the same curiosity that once led an ape to stand upright and look beyond the trees.

The shocking turns of evolution—the extinctions, mutations, migrations, and miracles—made us who we are. Every neuron in our brain, every beat of our heart, carries the memory of that journey.

We are not separate from our past; we are our past—living proof that from struggle can come consciousness, and from chance can come meaning.

The story of human evolution is not finished. It continues with every generation, every discovery, every question we dare to ask.

We are not the end of the story. We are its latest chapter—

and perhaps, its most astonishing.