For hundreds of thousands of years, humanity walked the Earth not as one species, but as many. Our ancestors were never truly alone. The modern human—Homo sapiens—is only the last survivor of a long and tangled lineage that once included powerful hunters, ingenious toolmakers, and mysterious beings whose bones whisper from the shadows of time.

When we look in the mirror today, we see the culmination of a story written not by one kind of human, but by an entire family—our lost cousins. They lived, loved, fought, and dreamed just as we do. They crafted tools, painted caves, buried their dead, and left behind faint echoes of intelligence that force us to rethink what it means to be “human.”

For most of our species’ history, the Earth was shared among multiple kinds of humans. We met them, lived beside them, and in some cases, mingled our blood with theirs. The story of our lost cousins is not just a tale of extinction—it is a story of kinship, survival, and the thin line that separates us from them.

The Family Tree of Humanity

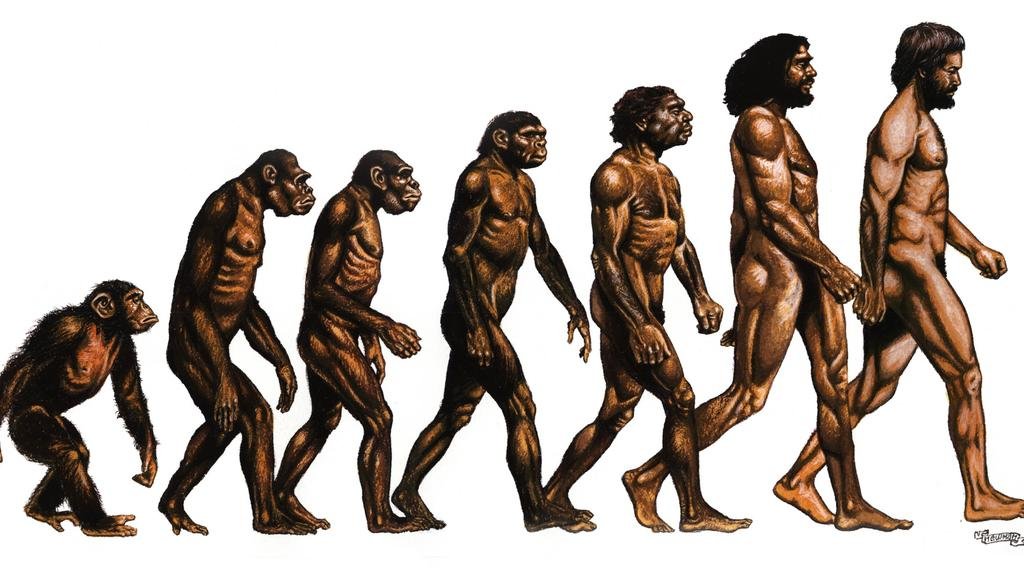

To understand our lost cousins, we must first understand where we fit in the great family of life. Humans belong to the biological group called hominins—a branch of primates that split from our common ancestor with chimpanzees about six to seven million years ago. From that point onward, evolution began to experiment, producing many different species that walked upright, made tools, and developed increasingly complex behaviors.

The path from ape to human was not a straight line—it was a vast, branching tree. At times, more than half a dozen human species lived at once across Africa, Europe, and Asia. Some were giants, others tiny. Some were brilliant toolmakers; others left behind only bones and stone flakes. Yet all of them shared something profound: the spark of humanity.

Our family tree includes Australopithecus afarensis—the species of the famous fossil “Lucy,” who walked the plains of Ethiopia over three million years ago. Then came Homo habilis, the “handy man,” who learned to shape stone tools. Homo erectus, the tireless traveler, became the first to leave Africa, spreading across Asia and Europe. Later came the heavy-browed Neanderthals, the delicate Denisovans, the diminutive Homo floresiensis, and the shadowy Homo naledi.

Each species carried a piece of the puzzle that would one day become us.

The Rise of Homo erectus — The Great Wanderer

About two million years ago, something remarkable happened. In the African savannas, a species emerged that would forever change the destiny of humanity. Homo erectus—“upright man”—stood taller, walked farther, and thought more deeply than any of its predecessors.

Homo erectus mastered the art of endurance. Unlike apes, who tired quickly, these early humans could run long distances across open land, chasing prey until it collapsed from exhaustion. They crafted sophisticated stone tools known as hand axes and may have been the first to control fire.

Their ingenuity allowed them to leave Africa and colonize the wider world. Fossils of Homo erectus have been found from Georgia to Indonesia, marking the first great human migration. For nearly two million years, they thrived—a record no species of human has ever matched.

It was Homo erectus who set the stage for all that followed. They were the pioneers—the ones who dared to leave home, who learned to adapt, who laid the foundation for humanity’s restless spirit.

The Neanderthals: The Shadow Within Us

If there is one lost cousin who still haunts our imagination, it is the Neanderthal. For decades, they were depicted as brutish, primitive cave dwellers—an evolutionary dead end. But science has rewritten that narrative entirely.

Homo neanderthalensis was no savage. They were intelligent, strong, and compassionate. Their bodies were built for the cold—short, muscular, and resilient, with broad noses that warmed frigid air. They lived across Europe and western Asia for hundreds of thousands of years, hunting mammoths, crafting tools, and surviving the brutal Ice Age landscapes.

Recent discoveries have transformed how we see them. Neanderthals buried their dead, sometimes with flowers or tools. They made jewelry from shells and animal teeth. They mixed pigments to create body paint. And inside caves like those in Spain, they left behind mysterious red symbols and handprints—some older than the arrival of Homo sapiens in Europe.

Most astonishing of all, we now know that Neanderthals were not separate from us. They were part of us. When modern humans left Africa around 60,000 years ago and met Neanderthals in the Middle East and Europe, the two species interbred. Today, every person of non-African descent carries about 1–2% Neanderthal DNA in their genome.

That means when you look in the mirror, a small part of you is Neanderthal. The shadow of that ancient cousin still lives within our cells, shaping our immune systems, skin, and even aspects of our emotions and metabolism.

The Neanderthals are not gone—they survive in us.

The Denisovans: The Ghost People of Siberia

For most of human history, we did not even know the Denisovans existed. Their discovery in 2010 came not from a fossilized skull or skeleton, but from a single fragment of a finger bone found deep within a Siberian cave. When scientists extracted DNA from the bone, they realized it belonged to an entirely new kind of human—closely related to Neanderthals but genetically distinct.

The Denisovans quickly became one of the greatest mysteries in anthropology. We still have only a handful of bones and teeth, yet from their genetic traces we know they once ranged widely across Asia. Their DNA lives on today in people from Melanesia, Australia, and parts of East Asia—proof that they, too, interbred with our ancestors.

They were master survivors, adapting to environments from icy mountains to tropical islands. Denisovan DNA even gave modern Tibetans a crucial gene that helps them breathe at high altitudes—a gift from a cousin species long vanished.

In life, Denisovans may have looked similar to Neanderthals, with robust features and large skulls. But we can only imagine their cultures, their songs, their myths—if they had them. They remain the ghosts of our past, known more through their genetic echoes than their bones.

The Hobbits of Flores

On a small island in Indonesia, scientists uncovered one of the strangest surprises in the human story. In 2003, they found the bones of tiny humans—just over a meter tall—with small brains and long arms. These were not deformed modern humans but a new species entirely: Homo floresiensis.

Nicknamed “the hobbits,” these little humans lived until about 50,000 years ago—at the same time as modern humans and Neanderthals. Despite their size, they crafted stone tools, hunted dwarf elephants, and used fire.

How did they become so small? Island life often leads to “island dwarfism,” where limited resources favor smaller body sizes. Homo floresiensis likely descended from Homo erectus who became trapped on Flores long ago and evolved to fit their new world.

Their discovery shook science to its core. It showed that the human story is far richer and more diverse than anyone imagined. Even in the age of Homo sapiens, the Earth still held other species of humans—each with their own adaptations, their own worlds.

The Enigmatic Homo naledi

Deep within the Rising Star cave system in South Africa, explorers crawling through narrow, pitch-black tunnels stumbled upon a hidden chamber. Inside lay thousands of bones belonging to a species no one had ever seen before.

Named Homo naledi, these beings stood about 1.5 meters tall with small brains but human-like hands and feet. They lived around 250,000 years ago—a time when modern humans were already emerging elsewhere in Africa.

What stunned scientists most was where the bones were found. The chamber was so remote that no animal could have dragged the bodies there by accident. The only explanation was deliberate burial—a ritual act previously thought unique to modern humans and Neanderthals.

If true, Homo naledi may have been capable of symbolic thought despite their small brains. Their existence forces us to question everything we thought we knew about intelligence. Perhaps consciousness and creativity do not depend solely on brain size.

A World of Many Humans

There was a time, not so long ago, when our world was home to at least half a dozen human species. In Africa lived Homo naledi and early Homo sapiens. In Europe and western Asia, Neanderthals thrived. In the East, Denisovans and Homo erectus endured. Farther south, on the islands of Indonesia, Homo floresiensis survived in isolation.

For thousands of years, these species overlapped, migrating, adapting, and occasionally encountering one another. Some competed for food and territory. Others exchanged ideas—or genes.

This mosaic world challenges the old view of evolution as a straight ladder. Humanity was never a single line of progress, but a web of experiments—some ending in extinction, others merging into new forms.

We are not the pinnacle of that story; we are simply its latest chapter.

The Dawn of Modern Humans

Around 300,000 years ago in Africa, a new species emerged—our own. Homo sapiens appeared with a combination of traits unseen before: a high, rounded skull, smaller face, and lighter body. But what truly set us apart was the mind.

Modern humans possessed an unprecedented capacity for imagination, language, and cooperation. They could plan hunts, create art, and share abstract ideas. This gave them a tremendous evolutionary advantage.

For tens of thousands of years, Homo sapiens remained in Africa, spreading slowly across the continent. Then, around 60,000 years ago, they began to venture outward—first into the Arabian Peninsula, then into Asia, Europe, and beyond.

Everywhere they went, they met other humans. Neanderthals in Europe. Denisovans in Asia. Perhaps even Homo floresiensis and Homo erectus in the islands. These meetings were not always violent. Sometimes, they led to exchange—and interbreeding.

Modern humans didn’t just replace their cousins; they absorbed them.

When Species Meet

The encounters between Homo sapiens and their cousins were among the most profound events in natural history. We can only imagine what those meetings were like. Did they see each other as strange, dangerous, or familiar? Did they share food, stories, or fear?

Genetic evidence shows that these meetings were intimate enough to leave lasting marks. Around 40,000–50,000 years ago, modern humans and Neanderthals interbred multiple times. Later, Homo sapiens met Denisovans in Asia, and those unions too left genetic legacies.

Some of our traits—such as certain immune system genes—came from these ancient interbreeding events. In a sense, every human alive today carries fragments of those encounters.

The boundaries between species were not as strict as we once believed. Humanity was, and is, a continuum.

The Fall of Our Cousins

Within a few thousand years of modern humans arriving in new regions, the other human species vanished. Neanderthals disappeared from Europe about 40,000 years ago. Denisovans faded from Asia soon after. The hobbits of Flores and their relatives likely died out around the same time.

Why? The reasons are complex and still debated. Climate change may have played a role, altering ecosystems faster than they could adapt. Competition with Homo sapiens—for food, shelter, and space—was likely decisive. Modern humans’ superior tools, organization, and communication gave them an edge.

But extinction is rarely simple. It may have been a slow fading, not a sudden annihilation—a gradual erosion of isolated populations until the last few were absorbed or vanished.

And in a deeper sense, they are not truly gone. Their genes, their legacy, and perhaps even their ideas live on in us.

The Legacy in Our DNA

Modern genetics has turned our genomes into a time machine. By sequencing ancient DNA from fossils, scientists can reconstruct the history written in our cells.

We now know that humans outside Africa carry Neanderthal DNA, while some populations in Oceania carry both Neanderthal and Denisovan DNA. Even Africans, once thought to have no such ancestry, bear traces of ancient interbreeding with unknown archaic humans.

These genetic legacies affect everything from how our immune systems respond to disease, to how our bodies adapt to cold or altitude. In some ways, our lost cousins helped us survive.

The human genome is not a pure lineage—it is a mosaic of interwoven histories. We are, quite literally, children of many worlds.

The Minds of Our Ancestors

For a long time, scientists believed that only Homo sapiens possessed symbolic thought—the ability to imagine, create, and communicate ideas through symbols. But discoveries over the last two decades have shattered that illusion.

Neanderthals made pigments and jewelry. Denisovans may have carved objects from bone. Even Homo naledi may have practiced burial rites. These acts suggest self-awareness, empathy, and a sense of meaning—qualities once thought uniquely ours.

Perhaps consciousness itself—this strange light that flickers behind the eyes—was not the gift of one species, but the inheritance of many.

When we imagine a Neanderthal gazing into the flames of a fire, or a Denisovan mother cradling her child beneath the stars, we glimpse the shared humanity that binds us across deep time.

What It Means to Be Human

The more we learn about our lost cousins, the more the boundaries of “human” begin to blur. If Neanderthals loved, created, and mourned, were they not human too?

Evolution did not produce a single, clear line dividing us from them. Instead, it gave rise to a spectrum—a family of beings, each carrying sparks of intelligence and emotion. We are the only survivors, but not the only humans that ever lived.

To be human, perhaps, is not just to survive—but to connect. To imagine. To remember. Those are traits our ancestors shared, regardless of species.

Their extinction does not erase their humanity. It deepens ours.

The Echo of Lost Voices

Every fossil we uncover is a whisper from our collective past. Each skull and bone tells a fragment of a story that belongs to all of us. When we look at those ancient faces—broad-browed Neanderthals, delicate Denisovans, tiny hobbits—we are not gazing at strangers. We are looking at family.

Somewhere deep in time, a Neanderthal child laughed. A Denisovan sang. A Homo erectus elder taught a younger hunter how to shape stone. Their moments of love, fear, and wonder were as real as ours.

Though they are gone, their echoes remain—in the DNA of our blood, in the shapes of our hands, in the fire of our minds.

The Story That Never Ends

The tale of humanity is not one of triumph alone. It is a story of loss, chance, and endurance. We are the product of countless experiments in survival—some successful, others forgotten.

But their story is not truly finished. As long as we remember them, as long as we seek their bones and listen to their DNA, our lost cousins live again—in science, in imagination, and in the shared identity of all who call themselves human.

When you walk under the stars tonight, remember that those same constellations once shone down on many kinds of humans. They looked up and wondered, just as you do now.

We are not the first to dream beneath the stars. And we are not the only ones who ever did.

Humanity has always been a chorus, not a solo. We were never alone—and perhaps, in some profound way, we never will be.