Long before the first cities rose, before the first words were written, before anyone dreamed of gods or kings, there was the Stone Age—the vast, silent expanse of time when our ancestors learned to shape the world with their hands. It was the age before history, when the story of humanity unfolded not in ink but in stone, bone, and fire.

For more than three million years, the Stone Age defined what it meant to be human. It was a time of extraordinary transformation: the birth of consciousness, the taming of nature, and the forging of tools that would one day build civilizations. From the earliest hominins who cracked pebbles to fashion cutting edges, to the artists who painted the walls of deep caves with images of life and spirit, the Stone Age was the crucible in which humanity itself was formed.

To understand the Stone Age is to gaze into a mirror of deep time—a reflection of who we were, how we learned, and why we endure. Though it lies far beyond the reach of memory, its legacy lives within us. The instincts that once guided our ancestors through wilderness and hunger still echo in our minds. The Stone Age is not a distant chapter—it is our origin story.

The Shape of Deep Time

When we speak of the Stone Age, we refer to the earliest and longest era of human existence, beginning with the first known use of stone tools and ending with the advent of metalworking. It spans an immense stretch of time—from roughly 3.3 million years ago to about 5,000 years ago, when bronze began to transform societies.

Archaeologists divide the Stone Age into three major phases: the Paleolithic (Old Stone Age), the Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age), and the Neolithic (New Stone Age). Each represents not just a technological stage but a fundamental shift in how humans lived, thought, and interacted with their environment.

Yet even these neat categories fail to capture the richness and diversity of Stone Age life. Across continents, climates, and species, the human story unfolded differently—sometimes in parallel, sometimes in isolation. What unites all these strands is the rhythm of adaptation, the endless dance between necessity and imagination.

The Birth of Tools

The story of the Stone Age begins with a single gesture: a hand lifting a stone. Around 3.3 million years ago, in what is now Kenya, an early hominin picked up a rock and struck it against another, breaking off sharp fragments. Those first flakes, crude yet purposeful, were the beginning of technology—the first step in humanity’s long quest to shape nature to its will.

The makers of these earliest tools were not Homo sapiens, nor even members of our direct species line, but likely Australopithecus or early Homo habilis. Their world was one of predators and scarcity, and the ability to cut meat, open bones for marrow, or fashion simple weapons offered a vital edge.

Over hundreds of thousands of years, toolmaking became an art of precision. Early humans learned to select the right stone, strike it with controlled force, and create edges suited for cutting, scraping, or piercing. This innovation—called the Oldowan industry—spread across Africa, marking the dawn of a cognitive revolution.

Each chipped stone represented more than survival. It was a thought made tangible, a connection between mind and matter. Toolmaking required planning, coordination, and imagination. In the sharp gleam of flint, humanity caught its first reflection of intelligence.

Fire: The Element of Transformation

If the tool was humanity’s first invention, fire was its first ally. The mastery of fire—perhaps as early as one million years ago—was a turning point that reshaped every aspect of existence. Fire provided warmth against cold nights, protection from predators, and the power to cook food, unlocking nutrients that fueled brain growth.

The control of fire is often associated with Homo erectus, a species that spread from Africa into Asia and Europe. Archaeological sites such as Wonderwerk Cave in South Africa and Zhoukoudian in China show evidence of hearths and charred bones dating back hundreds of thousands of years.

Fire was more than a tool—it was a symbol of mastery. Around it, early humans gathered, shared food, and told the first unrecorded stories. The flickering flames became the center of social life, a place where knowledge was passed down and cooperation took root. It also extended the human day, allowing thought and creativity to flourish after sunset.

The control of fire transformed not just diet and survival but psychology. It gave a sense of security in a dangerous world and perhaps inspired awe—a recognition that nature could be tamed yet never entirely controlled. In that glowing circle of warmth, the human imagination began to burn.

The Expanding Mind

As toolmaking and fire transformed daily life, another, subtler revolution unfolded within the human brain. Over millions of years, the hominin mind grew more complex, capable of foresight, language, and emotion.

By around 1.8 million years ago, Homo erectus exhibited signs of social cooperation and long-distance travel. Their tools grew more refined, leading to the Acheulean hand axes—symmetrical, teardrop-shaped implements crafted with remarkable skill. These tools reveal something profound: an aesthetic sense, a desire for order and beauty in function.

Brain size alone did not make humans exceptional. It was the emergence of symbolic thought—the ability to represent ideas and share them—that marked the true leap. Though language leaves no fossils, its traces appear in the sophistication of tools, art, and rituals. The rhythm of speech, the naming of things, and the storytelling that binds communities likely emerged during the later Paleolithic.

The mind that once only reacted began to imagine. It could now dream of what might be, not just what was. This imaginative consciousness would become the hallmark of humanity, allowing our ancestors to build societies, create myths, and explore worlds beyond sight.

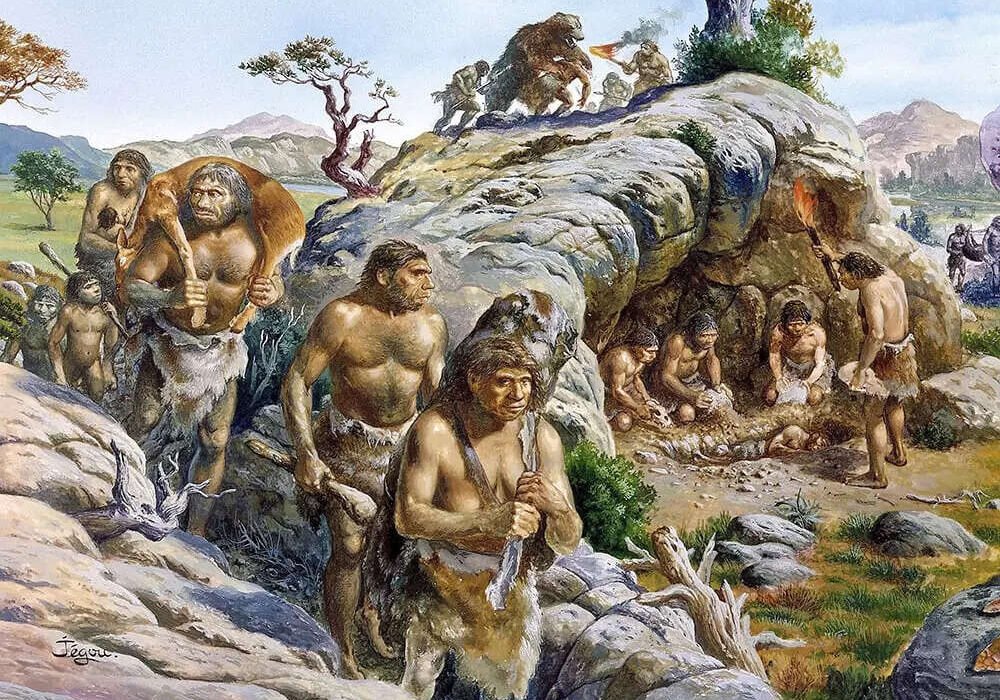

The Hunters of the Paleolithic

The Paleolithic era, spanning from about 3.3 million to 10,000 years ago, was the longest chapter in human history. It was an age of hunters and gatherers, of nomads moving through forests, savannas, and tundra in search of food. Life was precarious but deeply connected to the rhythms of nature.

During this time, Homo sapiens—our own species—emerged in Africa around 300,000 years ago. By 70,000 years ago, humans began migrating across the globe, reaching Asia, Europe, and eventually Australia and the Americas. They encountered new landscapes, climates, and other human species—Neanderthals in Europe, Denisovans in Asia—sometimes interbreeding with them.

The Paleolithic world was not primitive in the simplistic sense. Its people crafted complex tools, understood animal behavior, and managed ecosystems with skill. They developed language, kinship structures, and moral codes. They buried their dead, perhaps with rituals that hinted at a belief in an afterlife.

Caves became sanctuaries of art and mystery. In Lascaux and Chauvet in France, Altamira in Spain, and Sulawesi in Indonesia, walls bloom with painted horses, bison, and mammoths—images alive with motion and meaning. These works, some over 40,000 years old, are not mere decoration. They are expressions of identity, myth, and spirituality—a declaration that humans had begun to dream in symbols.

Neanderthals: The Other Humanity

Among the figures who populated the Stone Age, none have captured imagination more than the Neanderthals. They were not the brutish cavemen of old stereotypes, but intelligent, compassionate beings who shared much of our genetic and cultural heritage.

Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis) appeared in Europe and western Asia around 400,000 years ago. Stocky and muscular, with large brains comparable to our own, they were adapted to cold climates. They hunted large game, made sophisticated tools, used pigments, and perhaps even adorned themselves with ornaments.

Evidence from burial sites suggests they cared for the sick and honored the dead—a sign of emotional depth and social complexity. They thrived for hundreds of thousands of years, enduring multiple ice ages. Yet by 40,000 years ago, they vanished, leaving traces of their DNA in modern humans.

Why they disappeared remains a mystery. Climate instability, competition with Homo sapiens, and smaller population sizes all played roles. But their legacy endures—in our genes, in our resilience, and in the shared heritage of thought and empathy that makes us human. The Stone Age was not only our story—it was theirs too.

The Great Migrations

The Ice Age landscapes of the Paleolithic shaped humanity’s migrations. As glaciers advanced and retreated, they opened and closed pathways across continents. Humans followed herds, crossed land bridges, and settled new worlds.

From Africa—the cradle of humankind—waves of migration spread outward. One branch reached the Middle East and Europe, adapting to forests and tundra. Another moved eastward across Asia, eventually reaching Australia by 65,000 years ago. Later, around 15,000 years ago, humans crossed the Bering Land Bridge into the Americas, bringing with them the skills honed by millennia of survival.

These journeys were not random wanderings but deliberate acts of exploration. Each new land demanded adaptation: new tools, new shelters, new ways of thinking. In this ceaseless movement, humanity’s diversity blossomed. Skin color, language, and culture became mirrors of different environments—but beneath them all, the shared fire of curiosity burned.

The Mesolithic: Between Worlds

As the last Ice Age waned around 10,000 BCE, the Earth entered a period of profound change. Glaciers melted, sea levels rose, and climates grew milder. This transition, known as the Mesolithic or Middle Stone Age, was a bridge between the old nomadic life and the dawn of agriculture.

The Mesolithic was an age of experimentation. Forests replaced tundras, rivers teemed with fish, and humans adapted with new technologies—microliths, tiny precision-cut stones that could be mounted on arrows or harpoons. They built canoes, tamed dogs, and developed seasonal campsites.

It was also a time of greater regional diversity. Some groups remained nomadic hunters, while others began to settle, forming semi-permanent villages. The relationships between humans and their environment grew more intimate; they learned to manage resources, plant wild grains, and domesticate animals.

The Mesolithic world was neither primitive nor advanced—it was poised on the edge of transformation. Humanity stood at the threshold of a revolution that would alter existence forever: the rise of agriculture.

The Neolithic Revolution

Around 10,000 years ago, the world entered the Neolithic—the New Stone Age—and everything changed. In the fertile valleys of the Near East, humans began to cultivate wheat and barley, domesticate animals, and build permanent homes. The hunter-gatherer became the farmer, and the rhythm of life shifted from migration to settlement.

This Neolithic Revolution was one of the most profound turning points in history. With farming came food surpluses, population growth, and the first villages. Jericho, Çatalhöyük, and other ancient settlements reveal the beginnings of social organization, trade, and artistry. Pottery, weaving, and polished stone tools emerged, transforming daily life.

The relationship between humans and nature changed irreversibly. The Earth was no longer merely a home—it became a system to manage and control. Forests were cleared, rivers diverted, and animals bred for labor and food. This mastery brought prosperity but also new challenges: disease, inequality, and warfare.

The Neolithic mind still carried the echoes of its Paleolithic ancestors. In megalithic monuments like Stonehenge and Göbekli Tepe, one sees both engineering genius and spiritual yearning. The people of stone had become the builders of civilization.

The World the Stones Remember

Though the Stone Age ended thousands of years ago, its traces remain everywhere—carved into landscapes, buried beneath cities, etched into our DNA. The stone tools unearthed by archaeologists are not relics of savagery but symbols of intelligence and endurance.

The Ice Age valleys, the painted caves, the fire-blackened hearths—all whisper of lives lived with courage and creativity. Each artifact tells a fragment of the same story: that humanity was never static, never content merely to survive. From the first spark struck from flint, humans sought to understand, to create, to leave a mark.

Even now, our technologies are but extensions of that same ancient impulse. The smartphone and the spearhead share a lineage; both are born from the mind that seeks to shape the world. The Stone Age may have ended in chronology, but in essence, it continues.

The Mystery of the Human Spirit

What makes the Stone Age so compelling is not only its antiquity but its mystery. It is a mirror of our becoming—a time when humanity’s greatest questions began to stir: Who are we? Why do we exist? What lies beyond life and death?

The people of the Stone Age could not have imagined the future that would follow them—cities, empires, machines—but they laid its foundation. Their courage in facing a perilous world, their creativity in art and invention, their capacity for love and loss—all these qualities define us still.

To study the Stone Age is to rediscover our kinship with all those who came before. We are the heirs of their struggles, the keepers of their flame. The same intelligence that shaped a flint blade now builds spacecraft; the same hands that painted bison on cave walls now craft the technologies that probe the stars.

The Age That Made Us Human

The Stone Age was not an age of ignorance—it was an age of awakening. It gave birth to everything that makes us who we are: language, art, community, curiosity. It transformed fearful creatures into thinkers, wanderers into dreamers, and survivors into creators.

When we look at a stone tool, we are not just seeing an object—we are seeing a mind at work, a spark of thought that bridges millions of years. The mystery of the Stone Age is, ultimately, the mystery of ourselves. It is the story of how a species rose from the wilderness to understand its own existence.

The Stone Age ended, but humanity’s quest did not. We still chip away at the unknown, still light fires in the dark, still dream of worlds yet unseen. The stones may have fallen silent, but the hands that shaped them continue their work—in science, in art, in every act of creation.

The story of the Stone Age is not just history. It is the beginning of the human story, the first chapter of our long and unbroken journey toward understanding the universe—and ourselves.