Consciousness is the most intimate fact of existence and the most elusive phenomenon in science. It is the light by which we see the world—and yet it is the very thing that hides behind that light, beyond the reach of measurement. Every sensation, every thought, every flicker of awareness arises within it, but what is consciousness? How did a lifeless universe of atoms and forces give rise to minds capable of self-reflection?

From the earliest myths to modern neuroscience, humans have grappled with this enigma. Ancient philosophers believed consciousness to be the divine breath that animates life. Today, scientists search for its origins in neurons and networks. Yet the question remains as profound as ever: how does matter become mind?

To explore the origin of consciousness is to trace the story of awareness from its cosmic beginnings through the evolution of life, to the emergence of the human mind, and beyond—to the frontier where neuroscience, psychology, and philosophy converge. Consciousness, once the domain of poets and mystics, has become one of the most pressing and transformative scientific questions of our age.

The Ancient Question

Humans have always sensed that the spark of awareness sets us apart from the rest of nature. Ancient Egyptians believed the heart, not the brain, was the seat of the soul. In Hindu philosophy, consciousness—chit—is the very fabric of existence, an eternal witness underlying all phenomena. Greek thinkers like Plato saw the mind as the essence of the self, while Aristotle imagined it as the faculty that distinguishes the living from the nonliving.

For millennia, religion and philosophy framed consciousness as something immaterial, a divine essence breathed into flesh. The rise of science in the modern era brought a different view—one that sought to explain mind as an emergent property of matter rather than a separate realm. Yet the core mystery remained: even if we could understand every atom in the brain, could that ever explain the feeling of being alive, the vividness of experience, the “what it is like” to be a conscious being?

This dilemma, known as the hard problem of consciousness, was articulated by philosopher David Chalmers in the 1990s. The “easy problems,” he noted, involve explaining cognitive functions—how we perceive, remember, or speak. The hard problem, however, asks why those processes are accompanied by subjective experience at all. Why does the activity of neurons give rise to the taste of sweetness, the color red, or the ache of sorrow?

The Birth of Mind from Matter

To find the origin of consciousness, we must begin not in philosophy but in the physics and chemistry of the early universe. For nearly 10 billion years after the Big Bang, the cosmos knew no thought—only stars, galaxies, and the slow chemical alchemy of elements. Then, on a small rocky world orbiting a middle-aged star, something remarkable happened.

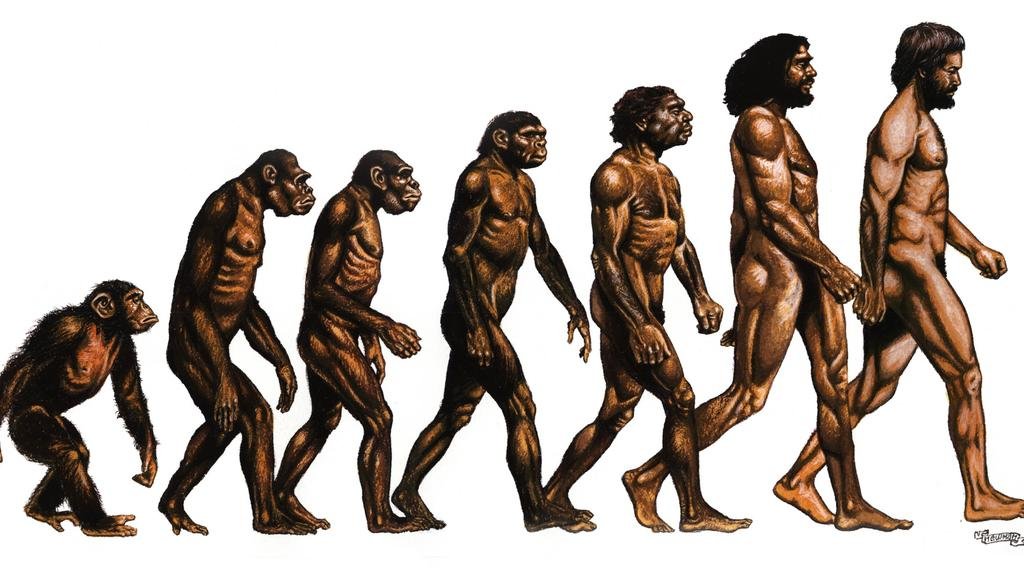

Atoms assembled into molecules that could copy themselves. From these self-replicating structures arose life—an organized defiance against entropy. Over billions of years, through natural selection, life grew in complexity. Cells became organisms, organisms formed nervous systems, and out of that biological machinery arose minds.

The earliest forms of consciousness were likely not self-aware but simply responsive. Primitive organisms could sense light, pressure, or chemical gradients, allowing them to move toward food and away from harm. This sentience—the ability to feel or react—was the seed from which awareness would grow. Over evolutionary time, as nervous systems became more intricate, sensations became richer, integrating memory, anticipation, and emotion.

The emergence of consciousness, therefore, was not a sudden event but a gradual unfolding—a continuum from basic responsiveness to reflective self-awareness. In this view, the roots of consciousness stretch deep into the tree of life, long before humans walked the Earth.

The Evolutionary Tapestry of Awareness

The story of consciousness is written in evolution’s long and tangled script. Early multicellular animals such as jellyfish and worms possess nerve nets that allow for basic coordination and sensing. These simple systems likely produce a faint glimmer of awareness—a rudimentary “feeling” of the environment without distinct perception.

As evolution favored creatures with faster reactions and better survival strategies, nervous systems centralized into brains. In fish and amphibians, we find the beginnings of structured sensory processing. Reptiles added emotion-like states, coordinating responses to threats and opportunities. Mammals developed the limbic system, the seat of motivation, attachment, and fear.

With the arrival of primates, neural circuits capable of planning, empathy, and social cognition began to flourish. The prefrontal cortex expanded, enabling individuals to model not only the world but themselves within it. Humans, with their vast cerebral cortex, took this recursive modeling to a new level. We became aware of being aware.

This evolutionary ladder suggests that consciousness evolved not as a luxury but as a tool for survival. Awareness allowed organisms to simulate possible futures, make choices, and learn from mistakes. A conscious brain could predict outcomes, coordinate group behavior, and adapt to complex environments. The human mind, though immeasurably more sophisticated, is built on these same ancient mechanisms of prediction, perception, and emotion.

The Brain: A Theater of Experience

Within the human brain, consciousness emerges as a dynamic interplay among billions of neurons. Each neuron is a biological transistor, exchanging signals through electrical impulses and chemical messengers. Yet no single neuron “feels” or “thinks.” Consciousness arises not from individual parts, but from their collective orchestration.

The brain can be thought of as a vast symphony of activity. The thalamus relays sensory inputs; the cortex integrates them into coherent perceptions. The limbic system colors these perceptions with emotion and meaning. Networks of neurons synchronize across regions, creating rhythmic patterns known as neural oscillations. These oscillations—particularly those in the gamma frequency range—are thought to bind together separate features of experience into a unified whole.

Modern neuroscience identifies certain brain regions that are crucial for consciousness. The posterior cortical “hot zone,” for example, integrates sensory experiences into a cohesive field of awareness. The prefrontal cortex, by contrast, contributes to self-reflection, decision-making, and the sense of agency. Yet even with these maps, the core mystery endures: how does the brain’s electrochemical activity translate into subjective feeling?

One promising framework is Integrated Information Theory (IIT), developed by Giulio Tononi. It proposes that consciousness corresponds to the degree of information integration in a system. The more a system’s parts interact to form a unified whole, the greater its consciousness. By this logic, even simple systems could possess minimal awareness, while the human brain—one of the most integrated structures known—represents a peak of subjective richness.

Another approach, Global Workspace Theory (GWT), likens the brain to a stage where information is selectively “broadcast” to multiple regions for processing. Only when data enters this global workspace does it become part of conscious experience. Competing networks vie for attention, and those that win shape our moment-to-moment awareness.

Both theories capture essential aspects of consciousness—its unity, selectivity, and integration—but neither yet explains why these processes feel like anything at all.

The First Glimmers of Awareness

If consciousness evolved gradually, what were its earliest forms? Some scientists argue that even simple animals such as insects or octopuses may experience a kind of sentience. Bees can recognize faces, remember tasks, and navigate using mental maps. Octopuses, with their distributed nervous systems, solve puzzles and exhibit play-like behavior. These abilities suggest an inner life, however alien.

At the molecular level, certain neural architectures may be necessary for consciousness. Brains with recurrent feedback loops—where information flows not just forward but backward—can sustain self-referential processing. Such loops enable an organism to distinguish between internal and external events, forming the basis of subjective experience.

Evolution thus built consciousness layer by layer: sensation, perception, emotion, memory, imagination, and finally self-awareness. Each new layer enriched the internal world, allowing creatures not merely to react but to experience their reactions. Consciousness became nature’s way of allowing life to model itself—an adaptive mirror in which evolution could refine behavior.

The Mirror of the Self

Human consciousness is unique not only for its complexity but for its self-reflective quality. We are aware not just of the world but of ourselves as observers within it. This capacity, often called metacognition, allows us to examine our thoughts, imagine others’ perspectives, and anticipate our own future.

The roots of self-awareness can be seen in other species. Chimpanzees and dolphins recognize themselves in mirrors. Elephants mourn their dead, suggesting an awareness of loss. Yet in humans, self-awareness reached a new threshold. The emergence of language amplified consciousness by giving it a symbolic form. Words allowed thoughts to be externalized, shared, and refined. Through language, humans could narrate their inner lives, turning private sensations into collective meaning.

This narrative capacity created what cognitive scientist Merlin Donald called “the symbolic mind”—a mind capable of constructing identity, memory, and culture. The sense of “I” that each person carries is thus both biological and social, forged by neural networks and by shared stories. Consciousness is not merely within us; it also exists between us, woven through communication and empathy.

The Role of Emotion and Meaning

Consciousness is not cold computation; it is suffused with feeling. Emotions give color and urgency to experience, guiding decisions long before reason intervenes. They are not primitive vestiges but central features of awareness.

Neuroscientist Antonio Damasio has shown that emotion and cognition are inseparable. The brain’s somatic marker hypothesis suggests that every decision is shaped by bodily feelings that encode past outcomes. Without these emotional signals, as seen in patients with certain brain injuries, rational thought becomes paralyzed.

Meaning, too, is born of emotion. We attend to what we care about, and care arises from the body’s drive to survive and flourish. Consciousness, in this sense, is not a detached observer but an active participant in life’s drama—a field where sensations, desires, and memories converge into a coherent self.

From an evolutionary perspective, emotions were consciousness’s first language—a pre-verbal system for valuing the world. Fear, curiosity, affection, and joy are ancient signals that taught living things how to act. The modern human mind still carries this legacy: beneath every thought lies a feeling, beneath every decision, a pulse of emotion.

Dreams and the Subconscious Landscape

Even when we sleep, consciousness does not vanish—it transforms. Dreams reveal the mind’s ability to generate entire worlds from within, blending memory, imagination, and emotion into surreal narratives.

During rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, the brain’s visual and emotional centers remain active while executive control subsides. This state allows the subconscious to play freely, exploring possibilities and resolving emotional tensions. Many scientists believe dreams serve vital functions: consolidating memories, simulating threats, or integrating experiences into the self.

Psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud saw dreams as the “royal road to the unconscious,” where repressed desires found symbolic expression. Modern neuroscience, though more empirical, still recognizes the subconscious as a vast reservoir of thought. Most of our mental activity—perception, decision-making, intuition—occurs below awareness, with consciousness emerging only as the visible crest of an immense cognitive ocean.

Thus, the origin of consciousness cannot be understood without acknowledging its shadow: the unconscious. They are not opposites but partners, the hidden and the revealed, the roots and the flower of the mind.

The Birth of Reflective Thought

The transition from basic awareness to reflective thought may have occurred in early humans through social and linguistic evolution. Anthropologists suggest that once language became complex enough to express abstract ideas, humans began constructing internal dialogues—thinking “in words.”

This inner speech allowed the mind to split into narrator and listener, creating self-reflection. Consciousness became not just awareness but commentary—a running monologue that integrates experience into a coherent identity.

Cultural evolution magnified this process. Storytelling, art, and ritual externalized mental life, making consciousness a shared phenomenon. Myths, religions, and philosophies emerged as collective mirrors of the human mind—ways to understand existence by projecting inner experience onto the cosmos. The very act of asking, What is consciousness? became a defining mark of consciousness itself.

The Neural Correlates of Consciousness

In modern neuroscience, the search for the neural correlates of consciousness (NCC) aims to pinpoint the minimal brain mechanisms required for subjective experience. Studies using functional MRI, EEG, and other imaging tools reveal that consciousness arises from distributed networks rather than a single “center.”

For visual awareness, activity in the occipital and parietal lobes integrates sensory data into stable images. For self-awareness, the default mode network—a set of regions active during introspection—plays a key role. Damage to or disruption of these networks can alter or extinguish consciousness, as seen in anesthesia, coma, or certain neurological disorders.

Yet the relationship between brain activity and conscious experience is not one-to-one. Identical neural patterns can produce different subjective states, depending on context and attention. This suggests that consciousness is not localized but relational—a dynamic process arising from the interaction between brain, body, and environment.

Consciousness Beyond the Human

Can machines ever be conscious? Could artificial intelligence develop subjective experience, or is consciousness uniquely biological? These questions press at the frontier of science and ethics.

If consciousness depends solely on information integration, as IIT suggests, then advanced AI systems might one day achieve it. But if it requires the embodied, evolutionary grounding of a living organism—feelings, metabolism, mortality—then machines may forever remain insentient mimics.

Meanwhile, the possibility that animals possess varying degrees of consciousness challenges human exceptionalism. Studies of corvids, dolphins, and cephalopods suggest complex inner lives shaped by social interaction and play. Consciousness, in this broader view, is not an all-or-nothing property but a spectrum—a continuum running from simple sensations to profound self-awareness.

The Quantum Hypothesis

A more controversial frontier is the idea that consciousness might be rooted in quantum processes within the brain. Physicist Roger Penrose and anesthesiologist Stuart Hameroff have proposed that microtubules—structural components inside neurons—could support quantum coherence, linking consciousness to fundamental physics.

While intriguing, this hypothesis remains unproven and hotly debated. Most neuroscientists argue that the brain’s warm, noisy environment would destroy quantum effects. Yet the allure of a deeper connection between mind and matter persists. If consciousness does have quantum roots, it might mean that awareness is woven into the fabric of reality itself—a modern echo of ancient philosophical intuitions.

The Emergent Mind

The majority of contemporary scientists view consciousness as an emergent property—a phenomenon that arises when complex systems reach a certain threshold of organization. Just as liquidity emerges from the motion of molecules, consciousness might emerge from neural complexity.

Emergence does not mean illusion. The mind is as real as any physical process—it is simply a higher-level pattern in the dance of matter and energy. In this framework, consciousness is not something added to the brain but something that is the brain, seen from the inside. Matter and mind are two aspects of one reality: the objective and the subjective faces of the same cosmic process.

This view bridges science and philosophy, suggesting that consciousness is not an anomaly but a natural outcome of evolution’s creative unfolding. When complexity and feedback reach a critical point, awareness ignites—like a flame emerging from the meeting of fuel and oxygen.

The Limits of Explanation

Despite immense progress, the origin of consciousness remains partly mysterious. No equation, however elegant, can yet translate the firing of neurons into the feeling of love or the taste of rain. Some philosophers argue that subjective experience may never be fully reducible to physical description—that consciousness represents an irreducible aspect of the universe, like space, time, or energy.

This panpsychist perspective, revived by thinkers such as Galen Strawson and Philip Goff, holds that consciousness may be fundamental—that even elementary particles possess a glimmer of experience, combining in complex ways to form human awareness. While speculative, this idea reflects a deep intuition: that mind is not a rare exception in the cosmos, but one of its intrinsic qualities.

Whether consciousness is emergent or fundamental, one thing is certain—it transforms the universe from a cold expanse of matter into a field of meaning. Through consciousness, the cosmos knows itself.

The Cosmic Mirror

Consciousness allows the universe to reflect upon its own existence. When you look at the stars, it is not merely you observing them—it is the cosmos observing itself through you. This poetic truth underscores the profound continuity between matter and mind.

From the fusion fires of stars came the atoms that form our brains. From those atoms arose thoughts, dreams, and awareness. Consciousness is, in a sense, the universe’s way of waking up. It transforms existence from a blind process into a lived story.

The ancient mystics intuited this long before science could articulate it: “The self and the cosmos are one.” Modern cosmology and neuroscience, in their own language, now echo that insight. The same physical laws that govern galaxies also govern the neural storms behind your eyes. And yet, within that storm, something inexplicable happens—the spark of subjectivity, the quiet miracle of “I am.”

The Future of Consciousness

As neuroscience advances, we may learn to map consciousness with greater precision, to induce or enhance it through technology, even to interface minds directly through neural networks. Yet such power raises profound ethical questions. What does it mean to alter awareness? To replicate or simulate it? To create machines that feel?

Meanwhile, meditation, psychedelics, and contemplative science are revealing that consciousness itself can expand beyond ordinary limits. Brain imaging shows that mystical and meditative states involve unique patterns of neural synchrony—suggesting that awareness can take on forms unimagined by everyday thought.

The study of consciousness may ultimately change not just our science but our sense of self. It reminds us that we are not mere observers of the universe but participants in its unfolding—fragments of stardust that learned to contemplate infinity.

The Infinite Mirror of Mind

The origin of consciousness is not only a question of biology or physics; it is a question of identity. To ask where consciousness comes from is to ask who we truly are. Are we chemical machines briefly animated by chance? Or are we expressions of something deeper—a universal awareness that finds form in every living thing?

Science may one day trace the precise neural pathways that generate experience. But the mystery will remain in a subtler form, for knowing how consciousness arises is not the same as being conscious. Each of us is both scientist and subject, observer and observed, the eye and the light that fills it.

Perhaps, in the end, consciousness did not “originate” at all—it has always been implicit in the universe, waiting for the right conditions to perceive itself. In the vast cosmic timeline, that awakening happened here, on a small blue planet, in minds that could wonder, dream, and love.

Through us, the universe became aware of its own beauty. Through consciousness, the cold void found warmth. Through the question itself—What is consciousness?—the cosmos whispers its own awakening.

And so, the origin of consciousness is not merely a scientific puzzle.

It is the greatest story ever told—the story of matter that learned to feel, of life that learned to know, and of a universe that, through the fragile window of mind, opened its eyes and saw itself for the first time.