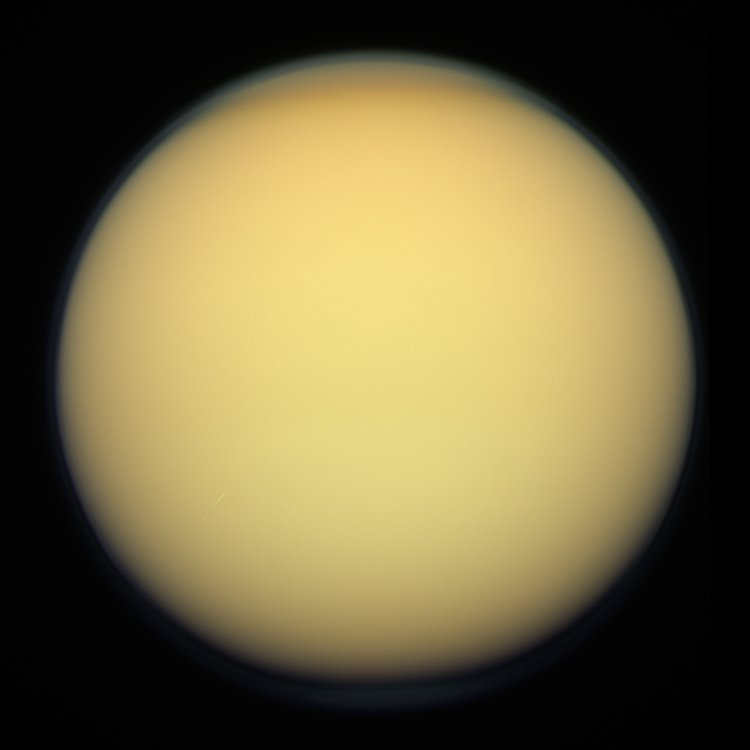

Among the countless worlds that orbit our Sun, few stir the imagination like Titan, Saturn’s largest moon. Shrouded in an orange haze, Titan is a world both alien and strangely familiar—a place where rivers flow, rain falls, and lakes shimmer under a golden sky. Yet this is no Earthly landscape. The rivers are made of liquid methane, the rain is hydrocarbon drizzle, and the lakes are frigid seas of ethane lying upon a crust of water ice colder than Antarctica’s heart.

Titan is a paradox—a frozen world that burns with chemical possibility. It is both a satellite and a world in its own right, larger than the planet Mercury and possessing a thick atmosphere unlike any other moon in the Solar System. To scientists, Titan is a natural laboratory—a time capsule preserving conditions that may resemble those of early Earth, before life began. In its clouds, seas, and dunes lies a story of chemistry, evolution, and perhaps, the faint stirrings of something more profound.

This distant world, orbiting a ringed giant nearly 1.4 billion kilometers from the Sun, holds answers to questions that stretch to the core of human curiosity: How did life begin on Earth? Could it emerge elsewhere? And what does Titan teach us about the limits—and the universality—of life itself?

Discovery and the First Glimpses

Titan was discovered in 1655 by the Dutch astronomer Christiaan Huygens. Using one of the most advanced telescopes of his time, Huygens noticed a faint companion orbiting Saturn—a point of light so small that he could not have imagined the world that lay behind it. He named it Titan, after the powerful gods of Greek mythology who preceded the Olympians—a fitting title for the mightiest of Saturn’s moons.

For centuries, Titan remained little more than a mysterious speck of light. Its true nature began to unfold only in the 20th century. In 1944, the Dutch-American astronomer Gerard Kuiper detected methane in Titan’s atmosphere using spectroscopy—a clue that this moon was enveloped in gases, unlike any other known moon. The existence of an atmosphere immediately set Titan apart; no other moon in the Solar System was known to possess one.

Then came the era of robotic explorers. In 1980 and 1981, NASA’s Voyager spacecraft flew past Saturn, capturing images of Titan’s opaque orange globe. Cameras could not pierce the smog, but instruments confirmed the presence of a dense nitrogen atmosphere, thicker even than Earth’s. Titan’s surface remained hidden, but scientists now knew they were dealing with a world of complexity.

It wasn’t until 2004, when the Cassini-Huygens mission arrived at Saturn, that the veil began to lift. Cassini orbited the planet for more than a decade, repeatedly passing Titan and mapping it with radar, infrared, and other instruments. In 2005, the European Space Agency’s Huygens probe descended through Titan’s atmosphere, landing softly on its surface. The images it sent back were breathtaking: channels carved by liquid, rounded pebbles, and a dimly lit horizon beneath a copper sky. Titan, it seemed, was not just a moon—it was a world alive with geological and meteorological activity.

The World Beneath the Haze

Titan’s most striking feature is its thick, hazy atmosphere. Composed primarily of nitrogen (about 95 percent) and methane (about 5 percent), it is the only dense atmosphere known to exist on a moon. At the surface, the pressure is 1.5 times that of Earth’s, meaning you could stand on Titan without a pressure suit—though the deadly cold, near -179°C, would freeze you instantly.

This atmosphere is both protective and mysterious. Sunlight filtering through it produces a perpetual orange twilight, even at noon. Complex chemical reactions occur high in the haze, where ultraviolet light from the Sun breaks apart methane and nitrogen molecules, allowing them to recombine into a zoo of organic compounds—hydrocarbons, nitriles, and tholins. These tholins, sticky reddish-brown particles, slowly fall to the surface like fine smog, coating everything with a dark veneer.

It is this smog that hides Titan’s landscape from visible light. Only radar and infrared instruments can penetrate the haze to reveal the surface below—a world both familiar and alien. Cassini’s radar maps showed lakes, dunes, mountains, and even possible cryovolcanoes. The surface is sculpted by processes that echo Earth’s, yet the materials are utterly different. Titan’s mountains are made of water ice as hard as rock. Its rivers carve through hydrocarbon plains. Its dunes stretch for hundreds of kilometers, formed not by sand but by frozen organic dust carried by winds.

A Symphony of Methane

Methane plays the role that water does on Earth. It exists in all three phases—gas, liquid, and solid—and cycles through the atmosphere, surface, and subsurface in a process eerily reminiscent of our planet’s hydrological cycle. On Titan, methane evaporates from lakes, forms clouds, condenses into rain, and falls back to the ground, feeding rivers that carve valleys and refill seas.

This methane cycle is one of the most remarkable discoveries in planetary science. It means that Titan, though frigid, is a dynamic world where weather and erosion actively shape the surface. Cassini observed storms and seasonal changes—darkening in the polar regions as methane rains fell, and shifting cloud bands that hinted at climate patterns.

The northern hemisphere of Titan hosts its largest bodies of liquid, including Kraken Mare, Ligeia Mare, and Punga Mare—seas of liquid methane and ethane larger than the Great Lakes of North America combined. These seas reflect radar like smooth glass, and some even show signs of waves and tides, driven by Saturn’s immense gravity.

Methane on Titan is constantly broken down by sunlight and should vanish within tens of millions of years—yet it persists. This implies an ongoing replenishment from the subsurface, possibly through cryovolcanism or chemical processes within Titan’s crust. Such replenishment hints at an active interior, suggesting Titan is not merely frozen but alive with internal energy.

Beneath the Surface: The Hidden Ocean

Beneath Titan’s icy crust, scientists believe there lies a vast internal ocean of liquid water mixed with ammonia—a world within a world. This subsurface ocean, inferred from Cassini’s gravity measurements and the moon’s rotation patterns, may lie 50 to 100 kilometers beneath the surface and extend hundreds of kilometers deep.

If confirmed, this ocean could make Titan one of the most promising places in the Solar System to search for life. Water is the solvent of biology as we know it, and where it exists in liquid form, even beneath ice, the potential for life increases. On Earth, microbes thrive in extreme environments—beneath glaciers, within hydrothermal vents, and inside rocks. Titan’s ocean, warmed by tidal forces from Saturn’s gravity, could harbor similar habitats.

The coexistence of a subsurface water ocean and a surface hydrocarbon environment makes Titan uniquely fascinating. It is the only known world with both liquid water and organic molecules—two essential ingredients for life. The challenge lies in their separation: the water ocean lies buried beneath a crust tens of kilometers thick, while the organics exist above. Yet on a geological timescale, impact events or cryovolcanic eruptions could mix these layers, potentially sparking prebiotic chemistry.

The Mirror of Early Earth

When scientists peer into Titan’s orange haze, they see echoes of a distant past—the Earth of four billion years ago. Before oxygen filled our skies, before plants and animals arose, our young planet was wrapped in a dense atmosphere of nitrogen, carbon dioxide, and methane. Sunlight and lightning struck these gases, creating organic molecules that rained upon the oceans, forming the raw ingredients of life.

Titan offers a living model of this primordial chemistry, frozen in time yet active in process. Its atmosphere hosts the same reactions that may have once occurred on early Earth. Laboratory simulations show that Titan’s atmospheric chemistry can produce amino acid precursors and complex organics. Tholins—those reddish substances that color Titan’s haze—contain a rich mix of carbon-based molecules, some of which may resemble the building blocks of life’s first steps.

On Earth, such molecules eventually found their way into warm, watery environments where they could assemble into more complex structures—perhaps self-replicating RNA or primitive cell membranes. On Titan, where liquid water is rare on the surface, this evolution may not occur in the same way. But in its subsurface ocean, shielded from radiation and warmed by internal heat, similar chemical symphonies might be playing out.

In this sense, Titan is more than a moon—it is a cosmic mirror reflecting our own origin story. By studying it, we glimpse what our planet might have looked like before life began, and we begin to understand the universal chemistry that could give rise to life elsewhere in the cosmos.

The Huygens Descent: Humanity’s Touch

On January 14, 2005, a small probe named Huygens entered Titan’s atmosphere after a seven-year journey aboard Cassini. As it plunged downward, it transmitted data and images for over two hours—a breathtaking glimpse into another world.

Through its cameras, scientists saw a world of muted colors and soft light. The probe descended through layers of orange haze, recording temperatures, pressures, and winds. At about 16 kilometers above the surface, Huygens emerged from the thickest clouds and captured the first clear images of Titan’s landscape: a network of branching channels resembling river valleys, leading toward a dark plain.

Then, gently, it landed. The surface beneath it was a mixture of frozen particles and rounded pebbles—evidence that liquids had once flowed there. The temperature measured -179°C, and the surface pressure was 1.47 times that of Earth. For 72 minutes, Huygens transmitted from the surface before its batteries faded, leaving humanity with one of the most haunting sets of images ever captured.

Those photographs, showing a dim orange horizon and a terrain shaped by flowing liquids, transformed our understanding of Titan forever. We had seen, for the first time, a world that felt eerily like home, yet utterly alien.

The Chemistry of Life’s Possibility

If life were ever to arise on Titan, it would not be life as we know it. The frigid environment and lack of liquid water on the surface make traditional biochemistry improbable. Yet scientists have begun to imagine alternative forms of life that could exist in Titan’s methane lakes.

In such conditions, cell membranes made of water-loving lipids would not survive. But chemists have proposed “azotosomes,” membranes composed of nitrogen-bearing molecules such as acrylonitrile—compounds that could remain stable in liquid methane. Laboratory models suggest these structures could function like biological membranes, encapsulating chemical reactions and perhaps even reproducing.

If such exotic life forms exist, they would represent a new branch of biology—methanogenic life based on a chemistry entirely foreign to Earth. While no evidence of life has yet been found, Titan’s potential forces us to expand our definition of habitability. It reminds us that life may not be limited to warm, watery worlds like our own, but could thrive wherever chemistry allows complexity to emerge.

Dunes, Mountains, and Cryovolcanoes

Titan’s geography is as varied as any planet’s. Its equatorial regions are dominated by vast dune fields, composed of dark organic sand carried by shifting winds. These dunes stretch for hundreds of kilometers, forming patterns reminiscent of the deserts of Namibia or Arabia—except that Titan’s dunes are made of frozen carbon compounds, not silica.

Toward the poles, the landscape changes. Lakes and seas cluster in depressions, possibly formed by dissolution or subsidence. Between them rise hills and mesas, while channels suggest the action of rainfall and runoff. Cassini’s radar revealed what appear to be cryovolcanoes—ice volcanoes that spew water and ammonia instead of molten rock. These cryovolcanic eruptions could bring material from Titan’s interior to the surface, perhaps linking the hidden ocean to the methane-rich exterior.

Mountains on Titan may reach several kilometers in height, formed by tectonic stresses as the crust flexes under Saturn’s tidal forces. Such features indicate that Titan’s surface, though ancient, is not static. Like Earth, it breathes, shifts, and reshapes itself over time.

Seasons Under a Distant Sun

Titan’s climate changes with the seasons, driven by Saturn’s 29.5-year orbit around the Sun. Each Titanian season lasts about seven Earth years, during which sunlight shifts from one hemisphere to the other, driving atmospheric circulation and storms.

During the Cassini mission, scientists observed seasonal transformations. Clouds gathered near the poles as summer approached, and methane rain darkened the surface in certain regions. Wind patterns reversed as sunlight shifted, reshaping dunes and altering weather systems. Titan’s atmosphere, though sluggish in its coldness, breathes with a rhythm as elegant as Earth’s.

These changes reveal Titan as a living world—not biologically alive, perhaps, but meteorologically vibrant. Its atmosphere is a theater of slow, chemical choreography, with clouds and winds tracing the pulse of a distant Sun.

Cassini’s Farewell and Titan’s Legacy

In 2017, after thirteen years orbiting Saturn, the Cassini spacecraft made its final descent into the planet’s atmosphere, burning up like a meteor. But its legacy endures, especially in what it taught us about Titan. Cassini’s instruments mapped more than two-thirds of Titan’s surface, measured its atmosphere with precision, and revealed it as one of the most Earth-like worlds in the Solar System—yet one sculpted from alien materials.

The data Cassini returned continues to fuel discoveries. It revealed how Titan’s methane lakes may evolve, how its atmosphere recycles organic material, and how its crust may conceal an ocean. The mission expanded our concept of habitability and our understanding of the chemistry that precedes life.

The Next Chapter: Dragonfly and Beyond

Titan’s story is far from over. In the coming decade, NASA’s Dragonfly mission will embark on a new journey to explore this enigmatic moon. Scheduled for launch in the mid-2030s, Dragonfly is a nuclear-powered rotorcraft—a flying laboratory capable of hopping across Titan’s surface to study multiple sites.

It will analyze organic chemistry, sample dune materials, and search for signs of prebiotic processes. It will measure the composition of the atmosphere and the structure of the surface, shedding light on how complex molecules evolve in such an environment. Most importantly, Dragonfly will help answer one of science’s greatest questions: Can the ingredients of life arise in a world so different from our own?

If all goes as planned, Dragonfly will land in the Shangri-La dune region near the equator and later journey toward Selk Crater, where an ancient impact may have once melted the icy crust, allowing water and organics to mix. It will be the first rotorcraft to explore another world, embodying the spirit of curiosity that has always driven human exploration.

Titan and the Nature of Wonder

Titan challenges us to rethink what it means for a world to be alive. It shows that the boundaries between planets and moons, between familiar and alien, are fluid. In its frozen methane seas and smoggy skies, we see echoes of our own beginnings—proof that chemistry, given time and energy, can weave complexity from simplicity.

Standing on Titan would be an otherworldly experience. The dim Sun would appear as a tiny disk, its light filtered through an orange haze. The air would be thick and still, the ground firm yet cold as stone. In the distance, a lake of liquid methane might glint faintly beneath the eternal twilight. You could take a step and leave a footprint that might remain undisturbed for millennia.

To explore Titan is to reach back in time—to the dawn of Earth’s history, when the first organic molecules danced in our planet’s young atmosphere. It is also to look forward, imagining futures where humanity learns to live on other worlds, drawing energy and inspiration from the vast diversity of nature.

The Methane Mirror

In the end, Titan is more than a curiosity—it is a reflection of what the universe is capable of. It shows that the same laws of chemistry and physics that shape our world also sculpt distant moons around distant planets. It teaches that life’s potential is not confined to warm, blue worlds but may lie hidden beneath orange skies and icy crusts.

Titan is a world of paradoxes: cold yet active, dark yet illuminated by knowledge, distant yet intimately tied to our understanding of ourselves. It is a place where rivers flow without water, where rain falls without warmth, and where the seeds of life may sleep beneath frozen seas.

For now, Titan remains silent, its mysteries veiled beneath its golden clouds. But with every mission, every image, and every spectrum of light, we draw closer to understanding it—and through it, to understanding the deeper story of life in the universe.

Titan reminds us that the cosmos is not empty but alive with possibility. It is the mirror in which we glimpse both our past and our potential—a methane world that, in its cold and alien beauty, reflects the warm beginnings of life on Earth.